“Trump Plans Tariffs on Mexico, Canada and China That Could Cripple Trade Bullshit.” This is from The New York Times. It’s fear mongering for the paradigm of corporate state media. In this essay, I tell the truth about tariffs and why the American worker needs them.

Ask yourself, do you see a lot of American-made cars in Europe? Not really. Why? Tariffs. Do you see a lot of European trucks in the United States. Not really? Again, tariffs. The European Union (EU) imposes tariffs on passenger vehicles imported from the United States to protect European industries. Does the United States put tariffs on EU passenger vehicles? Yes, but these tariffs are much lower than those imposed by the European Union. The EU tariff on passenger vehicles from the US is on average four times greater than the tariffs the United States imposes on EU passenger vehicles. That’s a lot of US cars not sold in Europe because the EU has made them cost prohibitive for a lot of European workers. There is a high tariff on light trucks (including pickup trucks and vans) imported into the US. The effect of these tariffs has been to protect those industries in America—and in protecting those industries, protecting manufacturing jobs for Americans.

What would be an effective way of compelling the EU to lower tariffs on US passenger vehicles? I think you can figure that out. The more fundamental question is whether you want your government to protect domestic automotive and other manufacturing and good paying jobs for Americans. Should Americans have good paying jobs? The corporate state doesn’t think so. Here’s why:

The progressive political class, which comprises the heart of the Democratic Party, serves those transnational corporate interests that seek lower wages in the United States because they benefit economically while spreading the myth than lower wages will correct the long-term fall in profits. To be sure, absolute and relative lower wages generate greater surplus value, but this occurs at the expense of aggregate purchasing power and hence undermines the system capacity to realize surplus value as profit in the market. This is the cause of periodic business recessions and overall lower standards of living, so it is no small matter.

Historically, tariffs had been a cornerstone of US economic policy, particularly for Republicans who saw them as a means to protect domestic industries. However, by the time Franklin Roosevelt assumed the presidency in 1933, the transnationalists—the same crowd that encouraged mass immigration—had convinced the masses that the Great Depression proved the harmful effects of high tariffs, particularly the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, which had exacerbated global economic decline by reducing international trade. (You will note that the tariff of 1930 occurred after the Stock Market crash of 1929 that triggered the depression.)

Roosevelt’s approach to tariffs marked a significant departure from the protectionist policies of his predecessors. Under the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA) of 1934, the administration gained the authority to negotiate bilateral trade agreements without requiring full congressional approval for each deal (not in itself a bad tool). The act shifted US trade policy from unilateral tariff-setting to a more multilateral, reciprocal framework. The RTAA allowed Roosevelt to reduce tariffs in exchange for similar concessions from other countries, fostering a climate of free trade hoping to revive global commerce during the depression.

Roosevelt’s tariff policies aligned with his broader New Deal goals of economic recovery and international cooperation (i.e., transnationalization). By reducing trade barriers, his administration aimed to open foreign markets to American goods, alleviate domestic overproduction, and strengthen ties with key trading partners. All this laid the groundwork for the post-World War II global economic system, eventually culminating in the establishment of institutions like the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO).

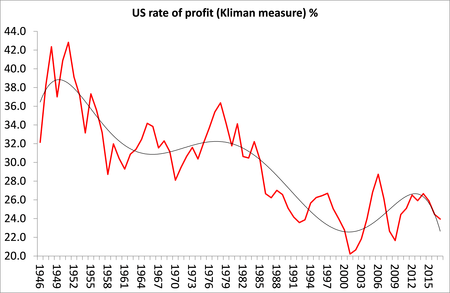

In Volume III of Capital, Karl Marx suggested that technological innovation can lead to a falling rate of profit by increasing the organic composition of capital (the ratio of constant capital to labor). However, the same effect can also be obtained by offshoring production and the importation of cheap foreign labor.

Everything the corporate class does—automation and mechanization, efficiency regimes, offshoring, mass immigration—undermines the capacity of the system to maintain a stable or growing rate of profit because it undermines effective organic demand by generating and exacerbating the redundancy of human labor. To be sure, the consumer can always spend beyond his means, but that amasses personal debt that enriches financial institutions, leading to greater concentration of wealth and providing more money capital for investments that advance the process of labor redundancy and wage suppression. Citizens who don’t have jobs, if a society is compassionate, drive up public debt as government becomes the provider for those who should (and could) be working. In this way, the costs of globalization are externalized, expecting the government to complete the cycle of capitalist production.

By reducing tariffs and encouraging international trade, Roosevelt aimed to alleviate overproduction in US industries by opening foreign markets to American goods. This may have temporarily bolstered profits in export-oriented industries that benefited from expanded markets. However, increased competition from imports compressed profit margins in industries facing foreign manufacturing. The reduction in tariffs and the resulting global economic integration led to intensified competition, which put downward pressure on prices and, by extension, profit rates. It also put downward pressure on wages. As international trade grew, US firms faced new competitive pressures that spurred capitalists to invest in labor-saving technologies.

A key factor contributing to the falling rate of profit is overproduction, where the market cannot absorb all goods at profitable prices. While freer trade may provide temporary relief by opening foreign markets, it at the same time integrates US capital more deeply into global cycles of production and crisis. The reduction in trade barriers exacerbated competitive pressures globally, contributing to an environment where profit rates continued to stagnate or decline.

Moreover, Roosevelt’s policies, including those reducing tariffs, were part of a broader New Deal agenda that included labor protections, wage increases, and social welfare programs. While these reforms improved domestic demand and stabilized the economy, they also increased labor costs for capitalists. This inorganic redistribution of surplus value from capital to labor also contributed to a compression in the rate of profit, especially in industries reliant on domestic market.

Tariffs did not cause the Great Depression. The perception that they did legitimized the transnationalist strategy of integrating the US work force into the global capitalist economy to the detriment of the American worker. We were tricked. We have pursued globalist economic strategies for long enough to know that it hurts American workers. Transnational corporations don’t care about American workers—and neither do the political elites that serve their interests. We need an economic nationalism focused on putting American workers first. We do that by raising tariffs on imports and forcing other economies to open their markets to our products.

It should have been obvious that a car and its parts manufactured in other countries creates few if any high-paying manufacturing jobs in America. Only cars and parts manufactured in the United States will accomplish that in any significant way. Tariffs will force other economies to allow our passenger vehicles to be competitive in other economies, and this will create more manufacturing jobs in America. So when Democrats tell you tariffs are bad, ask them who they are bad for. Obviously tariffs are good for European workers (who are still voting for the cultural elitism Americans rejected at the ballot box on November 5). If tariffs are good for European workers, why wouldn’t they be good for Americans workers, too? The answer to this question is obvious. And that’s precisely why the globalists don’t want tariffs.