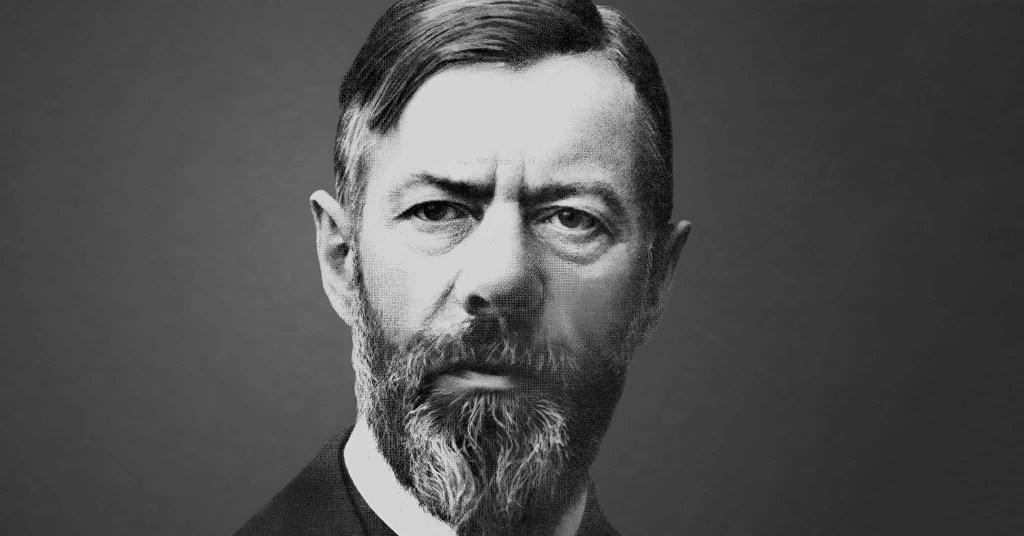

I teach social theory at a midsized state college in the Midwest. Social theory in my program is not separated into two courses, so I have to teach both classical and contemporary theory in one fourteen-week semester. Because so much contemporary theory is either rooted in classical theory or postmodernist nonsense, most of the content covers classical theory, with emphasis on Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, and George Herbert Mead. Because the role religion plays in social life is crucial to understanding human action, I have built in a substantial sociology of religion component.

I have suggested to my students a connection between Weber’s Protestant Ethic thesis and Marx’s critique of Bruno Bauer’s The Jewish Question. In today’s essay, I explore whether Marx anticipates Weber’s thesis concerning the spirit of capitalism and the role played by Protestantism in that development.

I want to begin with Weber’s observations in Ancient Judaism, published posthumously in 1921, which focuses on the unique socioreligious structure and historical consciousness that shaped Jewish life and thought. Why I start here will become obvious soon enough. Unlike the cyclical or unchanging worldviews of some Eastern religions, the Jewish perspective portrayed the world as a dynamic, historical process with a clear purpose and endpoint. Weber highlights how Jewish theology framed the world as a temporary structure awaiting a divinely mandated reordering of things, one that would ultimately reestablish Jewish dominance and harmony with God’s will. Weber describes an ethical rationalism in Jewish thought that shapes a unique approach to social conduct, one emphasizing moral accountability and responsibility over magical or mystical elements.

This ethic, according to Weber, forms a core part of the Western (Europe and North America) and Middle Eastern (West Asia and North Africa) ethical foundation from which both Christianity and Islam emerge respectively. Judaism thus represents a crucial turning point—a “pivot”—in Western and Middle Eastern social evolution, marking a shift toward a future-oriented, ethical framework that has influenced broader cultural and religious traditions.

In the story of the Jewish people, a dialectical process involving transformative forces is apparent. From a biblical perspective, God throws obstacles before the Jews for them to overcome and move to a higher unity. In the Hebrew Bible, the figure of Satan, which means “adversary” or “accuser,” is quite different from the Christian conception. Satan in Judaism is not an autonomous source of evil opposing God but rather a divine agent tasked with testing human resolve and moral integrity. In the Jewish view, obstacles are not inherently evil but instead provide opportunities for growth, self-discovery, and greater unity with God. (For more on the Christian conception of Satan, see my Zoroastrianism in Second Temple Judaism and the Christian Satan, which I penned on Christmas Eve 2018 while at my Mother’s house in Tennessee.)

Judaism’s focus on testing and overcoming obstacles cultivates a worldview grounded in engagement with the material world. While many religious texts focus on stories about the exploits of the gods, the Hebrew Bible is the story of a people. Rather than perceiving worldly existence as something to transcend (as might be found in Christian or Gnostic views), Judaism sees human action in history and the world as crucial. Through action, effort, and struggle, one realizes divine purposes, bringing creation closer to its ideal form. This engagement with the material and historical world has been foundational in Jewish thought and practice, producing an ethic of resilience and a worldly focus that values tribal ties and historical progress.

This theme of struggle and synthesis was influential for Georg Hegel, whose dialectical approach sees history as an unfolding process in which contradictions drive development. The process is one of becoming, a process where progress emerges through conflict and resolution, emphasizing the movement of concepts through contradiction, negation, mediation, and sublation (Aufhebung), revealing the inherent unity within opposition and a higher unity through resolution. Hegel finds inspiration in the Jewish conception of history as dynamic and directed by challenges. He views history as the realm in which human freedom and rationality unfold through struggle, ultimately seeking unity in a higher order of things. Though Hegel developed his dialectic in the light of a broader Christian philosophical framework, his emphasis on worldly struggle and progress through contradictions shows a strong resonance with this aspect of Jewish thought.

In Ancient Judaism, Weber discusses how the Jewish God’s demands are often exacting, framing obstacles as tests of moral and spiritual resilience. This view leads to a focus on ethical action, rather than merely escaping the world or achieving personal salvation. Weber suggests that this historical outlook sets Judaism apart from many ancient religions, as it emphasized moral behavior within the material world as a central aspect of fulfilling the divine will. Weber also connects this worldview to the notion of a dialectical process (albeit he doesn’t work from an explicitly Hegelian standpoint). Weber describes how the Jewish people faced cycles of suffering and redemption, interpreting each setback as part of a divine plan that requires human agency for its fulfillment. This focus on historical engagement and overcoming adversities through human action aligns with Hegel’s view that history is a dynamic process of development driven by conflict and resolution.

“For the Jew,” Weber writes in Ancient Judaism, “the social order of the world was conceived to have been turned into the opposite of the one promised for the future, but in the future it was to be overturned so that Jewry could be once again dominant. The world was conceived as neither eternal nor unchangeable, but rather as being created. Its present structure was a product of man’s actions, above all those of the Jews, and of God’s reaction to them. Hence the world was a historical product designed to give way to the truly God-ordained order.” The God-ordained order is the achievement of the highest unity. “There existed in addition a highly rational religious ethic of social conduct,” Weber continues, “free of magic and all forms of irrational quest for salvation; it was inwardly worlds apart from the path of salvation offered by Asiatic religions. To a large extent this ethic still underlies contemporary Middle Eastern and European ethics. World-historical interest in Jewry rests upon this fact.” From this he draws a profound observation: “Thus, in considering the conditions of Jewry’s evolution, we stand at a turning point of the whole cultural development of the West and the Middle East.”

* * *

In his essay “Zur Judenfrage” (“On the Jewish Question”), published in 1844 in Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, nearly eighty years before the appearance of Ancient Judaism, Marx explored the relationship between Judaism and the socioeconomic structures of society, particularly within the context of Christianity and civil society, i.e., the capitalist mode of production. Marx proceeds via a critique mainly of Bruno Bauer’s Die Judenfrage (The Jewish Question), published in 1843, but also Bauer’s “Die Fähigkeit der heutigen Juden und Christen, frei zu werden” (“The Capacity of Present-day Jews and Christians to Become Free”), published in Georg Herwegh’s Einundzwanzig Bogen aus der Schweiz.

Bauer argues that Jews should not be granted political emancipation until they relinquish their religious identity. In his view, the persistence of a distinct Jewish identity is incompatible with the secular, universal rights needed for modern citizenship. Bauer contends that true political emancipation requires the abolition of religion altogether. He sees religion as a barrier to universal human rights and believes that a secular state, free from religious influence, is necessary for genuine emancipation. Bauer criticizes the special privileges that various religious groups, especially Jews, seek within the state, arguing that such privileges undermined the principles of equality and universal rights. Crucially, in Bauer’s way of thinking (and this is true for Marx, as well) the Jewish identity is centered on religious belief and not matters of ethnicity or race.

In his critique of Bauer, as he is wont to do, Marx shifts the focus from religious identity to economic and social structures, exploring the nature of political emancipation and the broader context of human emancipation beyond political rights. He criticizes Bauer for not recognizing the deeper socioeconomic dimensions of emancipation and, as expected, argues for a more radical transformation of society. In this shift, Marx contends that Judaism’s practical spirit has flourished within Christian societies; the Jew is not an isolated religious figure, but a representative of the broader societal tendencies toward egoism and practical need. Now we come to it; the thesis of the present essay thus becomes explicit: is it the case that the Protestant ethic Weber identifies in his earlier work The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904-05) as enabling the development of the capitalist spirit is actually the perfection of Judaism in the totalization of capitalist relations identified by Marx.

By egoism, Marx means individualism, which is the political emancipation offered by the liberal state, which is to say that liberalism elevates individual self-interests over communitarian ethics, a process I have referred to in the past as “detribalization.” Liberated from their tribe, the individual is reincorporated into the national structure emphasizing equality under the rule of law. This focus is associated with Marx’s interest in alienation, where individuals become disconnected from communal bonds and social solidarity and thus estranged from other men and self (since self is also a social product). Marx thus distinguishes between political and human emancipation, the latter involving the transformation of social relations to overcome the alienation inherent in capitalist society. Under these new arrangements, human beings are free to develop their capacities in conjunction with others, rather than in competition with them. (See The Postmodern Condition: Human Nature, Tribalism, and the Future of the Nation-State.)

Marx identifies practical need and egoism as the core principles of civil, or bourgeois society. He argues that in the monotheism of the Jew money becomes a deity—indeed, the central deity. In Marx’s view, money as the ultimate value degrades all other aspects of human and natural life into mere commodities. The dominance of money, Marx contends, has secularized the Jewish god, transforming Yahweh into a universal symbol of self-interest and economic exchange. Moreover, Judaism reduces human relations, including gender relations, to transactions. This commodification extends to all aspects of life under the influence of money and private property, reflecting a broader societal contempt for nature and intrinsic human values. Marx also critiques the Jewish emphasis on legalistic adherence, viewing it as a reflection of the bureaucratic and self-interested nature of civil society.

Judaism reaches its zenith with the perfection of civil society, Marx observes, which occurs within the Christian world. Christianity facilitates the complete separation of civil society from the state, promoting egoism and atomistic individualism. He describes Christianity as the theoretical elevation of Judaism’s practical concerns, while Judaism represents the common practical application of Christian principles; thus Christianity and Judaism are interlinked, with Christianity emerging from Judaism and ultimately merging back into it. This interdependence reflects a broader process of alienation and commodification in society, where human and natural values are subjugated to the imperatives of money and self-interest.

Marx argues that the tenacity of the Jew is not due to his religion per se, but to the underlying human basis of his religion, namely egoism. In modern civil society, egoism is universally realized and secularized, making it impossible to convince the Jew of the unreality of his religious nature. Marx concludes that the nature of the Jew is not merely a reflection of individual narrowness but embodies the broader societal narrowness shaped by practical need and self-interest. Thus Marx equates Jewish identity with capitalist practices, suggesting that the “worldly religion of the Jew” is “huckstering” (meaning to promote or sell) and implies that the emancipation of Jews is intertwined with the emancipation of society from capitalism.

Marx writes that “Judaism reaches its highest point with the perfection of civil society, but it is only in the Christian world that civil society attains perfection. Only under the dominance of Christianity, which makes all national, natural, moral, and theoretical conditions extrinsic to man, could civil society separate itself completely from the life of the state, sever all the species-ties of man, put egoism and selfish need in the place of these species-ties, and dissolve the human world into a world of atomistic individuals who are inimically opposed to one another.” He continues: “From the outset the Christian was the theorizing Jew, the Jew is, therefore, the practical Christian, and the practical Christian has become a Jew again.” Then, controversially, “The social emancipation of the Jew is the emancipation of society from Judaism.”

Marx argues that true emancipation, whether for Jews or others, cannot be achieved solely through political means within a capitalist society, which he sees as inherently alienating. Political emancipation is only partial freedom; it allows individuals to be legally equal but does not address the deeper social structures that lead to economic inequality and human alienation. Political rights, in Marx’s view, give individuals formal freedoms without transforming the social conditions that foster real human liberation. Marx thus suggests that “solving” the Jewish question, which is at once the solution for the broader problem of human emancipation, requires transcending the capitalist system altogether. He views capitalism, the “world of hucksters,” as a system that perpetuates division and self-interest. Emancipation for any marginalized group, including Jews, would only be possible if society as a whole were liberated from the constraints of private property and class antagonism.

Marx argues that the traits he associates with Judaism—egoism, materialism (in the commercial sense), and self-interest—find their full expression and “perfection” within a Christianized civil society, one where economic self-interest dominates and individuals exist as atomized entities, disconnected from collective “species-ties.” In this worldview, Marx sees Christianity—and he is I presume speaking of Protestantism here—as the “theorizing” form of Judaism, where the separation of the state and individual material interests becomes complete. The goal of “social emancipation,” in Marx’s view, requires freeing society from the egoistic values he attributes to “Judaism,” thus abolishing the primacy of individual material gain over collective human connection.

Marx’s solution to the Jewish question thus lies in winning the struggle for a communist society, ie., classless and stateless social arrangements, where people are not defined by economic, religious, or social divisions but by their collective humanity, or species-being (Gattungswesen). For Marx, humans, unlike other animals, are capable of consciously shaping their world through labor and are inherently collaborative beings. By abolishing private property and class exploitation, Marx envisions a world in which individuals could attain true freedom and community beyond the limitations imposed by capitalist society and return to harmony with the species-being. The Jew thus goes away not in the eliminationist or genocidal sense offered by the Nazi but rather in the sense that, without the need for religious or other ideological affinities, there are no religious groups at all. In other words, Christians and Muslims go away with the Jews; in all cases, the people remain.

* * *

Weber and Marx offer distinct, yet intersecting interpretations of Judaism in relation to social and historical development, each viewing Judaism through the lens of broader cultural dynamics. Weber’s perspective centers on Judaism’s foundational impact on Western and Middle Eastern ethical development, particularly its rational, future-oriented ethics. For Weber, Judaism’s unique historical view—one that saw the current world order as provisional and human actions as pivotal to its unfolding—was revolutionary. He argues that Judaism introduced a linear, purposeful, even teleological conception of history, with a moral order that emphasized individual responsibility and rational conduct. This ethical rationalism, he suggests, laid groundwork for Western moral systems, differentiating it from other ancient religious traditions. (Some take it further than this. For example, Yale professor David Gelernter argues that Judaism calls upon Jews to be separate themselves from other groups in order to sit in judgment based on their moral standpoint. See my 2009 essay An Obnoxious Chauvinist.) For Weber, Judaism represents a turning point that helped shape the Western focus on law and morality, making it a crucial element in understanding the origins of contemporary Western ethics.

Marx approaches Judaism not as an ethical foundation but as a metaphor for the self-interested materialism he critiques in modern capitalism. He frames Judaism within the socio-economic context of civil society, asserting that “Judaism” is synonymous with the values of egoism, individualism, and materialism. In Marx’s view, these qualities find their ultimate expression in the capitalist world shaped by Christianity. He sees Christianity as enabling civil society to split from the state, allowing individual economic interests to eclipse communal ties. This structure, for Marx, represents the dominance of economic individualism over collective social values, where the individual operates solely out of self-interest, creating a fractured society that is “emancipated” from shared humanity and ethical bonds. In his polemic, the “social emancipation of the Jew” equates to society’s liberation from the “Judaism” that he equates with capitalist egoism, suggesting a need for social cohesion beyond individual material concerns.

In examining both theorists together, some might suppose opposing evaluations. Weber sees Jewish ethics as an essential contribution to a rational moral order, one that elevated the West’s ethical landscape. For Marx, the values he associates with Judaism—refracted through his critique of economic life in a Christian-dominated world—symbolize the rise of alienation and egoism that need to be overcome. Weber’s view is grounded in the ethical and historical developments Judaism inspired, which he considers essential to the development of Western civilization.

But are these opposing evaluations as some might suppose? As implied above, I don’t think so. As noted, well before Ancient Judaism, Weber published his two-part essay The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism in the journal Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik (Archive for Social Science and Social Policy). There he articulates how religious asceticism initially drove the development of a rational order that would later become foundational to capitalism.

For Weber, a particular ethic embedded in certain Protestant denominations, particularly Calvinism, fostered a mindset conducive to capitalism. Weber believed that Calvinist principles, such as the doctrine of predestination and the importance of a “calling,” encouraged individuals to pursue hard work, discipline, and frugality as a means of demonstrating their worthiness. Over time, these values contributed to a rational economic ethos, supporting the growth of capitalist structures, particularly in Western Europe and America.

Paradoxically, with the rise of capitalism, material accumulation and organized efficiency replaced the spiritual motivations that originally guided work, and over time the religious framework gave way to secularized capitalism, which no longer relied on a religious ethic, but continued to demand structured, disciplined labor. Weber believed that capitalism transformed its original religious values into a self-perpetuating system that, in the end, destroyed the very values that had underpinned it. This has been termed by contemporary theoretician George Ritzer “irrationality of rationality.”

Weber writes in his essay, “Since asceticism undertook to remodel the world and to work out its ideals in the world, material goods have gained an increasing and finally an inexorable power over the lives of men as at no previous period in history. Today the spirit of religious asceticism—whether finally, who knows? —has escaped from the cage.” He continues: “But victorious capitalism, since it rests on mechanical foundations, needs its support no longer. The rosy blush of its laughing heir, the enlightenment, seems also to be irretrievably fading, and the idea of duty in one’s calling prowls about in our lives like the ghost of dead religious beliefs.” Then, “In the field of its highest development, in the United States, the pursuit of wealth, stripped of its religious and ethical meaning, tends to become associated with purely mundane passions, which often actually give it the character of sport.”

For Weber, this secularized rationality under capitalism finds a situation where the once spiritually motivated Protestant ethic has faded, leaving workers trapped in impersonal systems. Capitalism, which once rested on an Enlightenment optimism, moved by a Promethean spirit, had become or was everywhere becoming “stripped of its religious and ethical meaning.” The “pursuit of wealth” becomes “associated with purely mundane passions,” a shift that Weber sees most vividly in the United States where labor becomes a rationalized, mechanized pursuit that transforms individuals into components of a larger system, valuing economic productivity over personal fulfillment or spiritual meaning.

“Military discipline is the ideal model for the modern capitalist factory,” observes Weber. “Organizational discipline in the factory has a completely rational basis. With the help of suitable methods of measurement, the optimum profitability of the individual worker is calculated like that of any material means of production.” He continues: “On this basis, the American system of ‘scientific management’ triumphantly proceeds with its rational conditioning and training of work performances, thus drawing the ultimate conclusions from the mechanization and discipline of the plant. The psycho-physical apparatus of man is completely adjusted to the demands of the outer world, the tools, the machines—in short, it is functionalized, and the individual is robbed of his natural rhythm as determined by his organism; in line with the demands of the work procedure, he is attuned to a new rhythm though the functional specialization of muscles and through the creation of an optimal economy of physical effort.”

Under such systems, individuals become highly specialized, functionally attuned to machines and industrial demands that strip them of their “natural rhythm.” Scientific management involves training individuals to become so attuned to the needs of the factory or bureaucratic state that their very psycho-physical apparatus is reshaped to maximize efficiency. Here, Weber captures a profound dehumanization: individuals are no longer valued for their intrinsic humanity or creativity, but rather for their utility within the rationalized system. Weber writes, “This whole process of rationalization, in the factory as elsewhere, and especially in the bureaucratic state machine, parallels the centralization of the material implements of organization in the hands of the master. Thus, discipline inexorably takes over ever larger areas as the satisfaction of political and economic needs is increasingly rationalized. This universal phenomenon more and more restricts the importance of charisma and of individually differentiated conduct.”

This observation is echoed in Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, where he discusses the “animality of man.” Gramsci, a Marxist, critiques the asceticism promoted by bourgeois and bureaucratic ideologies, which seek to regulate not only labor but also leisure and private life. This Puritanical control denies individuals the full range of their human experience, including the “animal” pleasures of the body, such as enjoyment, rest, and play. Such a system enforces a mechanical efficiency that prioritizes productivity and obedience, stripping people of the very pleasures and freedoms that make life meaningful. Thus Gramsci viewed the functional denial of human vitality as part of a broader strategy to maintain social order. By suppressing instincts and channeling energy exclusively into work or compliant behavior, hegemonic systems prevent individuals from fully experiencing their humanity. This is a subtle but effective way of dehumanization: not by reducing people to animals in a crude way, but by denying them access to the joys and instincts that connect them to their natural being.

Weber argues that rationalization extends beyond the factory and workplace to the bureaucratic state, where power and control are increasingly centralized. This centralization of material resources in the hands of the master not only reflects the economic concentration that Marx critiqued but also a social concentration of power that restricts personal agency. Weber explains that bureaucratic discipline colonizes the lifeworld, creating a highly organized, depersonalized social structure where individual charisma or freedom loses significance. This mirrors Marx’s argument on alienation, where workers are estranged from the products of their labor and from each other, treated as interchangeable units within a mechanized, impersonal process.

Thus both Weber and Marx scrutinize the impact of capitalist rationality on the human spirit, albeit through distinct frameworks, one idealist, the other materialist. Marx argues that capitalism alienates individuals by reducing them to productive inputs, estranged from the products they create and from one another. For Marx, the capitalist system objectifies human beings, exploiting them for their labor while concentrating the means of production in the hands of a few, thereby intensifying class divisions and rendering workers increasingly powerless. In The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Weber similarly laments capitalism’s reduction of individuals to cogs in the bureaucratic machinery, where disciplined labor has become an impersonal, mechanized process devoid of spiritual meaning or ethical grounding.

Both theorists thus critique the rationalization inherent in capitalist structures, which transform work from a potentially meaningful or ethical activity into an instrument of profit. Weber traces the historical roots of this transformation to the ascetic Protestant ethic, which sanctified disciplined labor as a calling. Yet as capitalism secularized, this sense of purpose evaporated, leaving behind a disenchanted economic structure driven by efficiency rather than ethical fulfillment. Where Protestantism once infused work with religious value, modern capitalism has stripped labor of meaning, leaving “the ghost of dead religious beliefs.” Marx and Weber both recognize this dehumanizing shift, but while Marx more explicitly attributes it to class exploitation and the concentration of capital, Weber attributes it to the consequences of a general culture of rationalization, where individuals become subsumed within impersonal systems governed by economic calculation.

In the end, they’re talking about the same thing. Weber’s depiction of the capitalist system echoes Marx’s notion of alienation. In his analysis of “scientific management,” Weber describes how capitalist organization trains workers to conform to the demands of machinery, optimizing their physical and mental capacities to fit the needs of industrial production. This functionalization mirrors Marx’s description of estrangement from species-being, in which labor becomes something external to the worker—a mere means to survive, rather than a fulfilling or self-actualizing activity. In this context, both thinkers recognize the depersonalizing effect of capitalist rationality, which treats labor not as a source of human dignity but as a commodity to be measured, optimized, and controlled.

Both Marx and Weber also observe the concentration of power within the capitalist system. Marx attributes this concentration to class dynamics, where the “master” class monopolizes the means of production, systematically disempowering workers. Weber similarly sees capitalism concentrating control, focusing on the bureaucratic machinery that centralizes authority in a way that restricts individual autonomy. For Weber, the bureaucratic state and capitalist enterprise both contribute to a form of disenchantment, where rationalization encroaches on every aspect of life, ultimately subordinating personal values and autonomy to the dictates of a system that prioritizes efficiency over humanity.

* * *

Both The Protestant Ethic and Ancient Judaism explore how different ethical systems, stemming from unique theological frameworks, impact the society’s orientation towards the world, including economic activities. However, while Protestantism’s ethics dovetailed with and supported the rise of capitalism, Judaism’s ethical monotheism did not prioritize worldly success in the same way, remaining more focused on survival and cohesion within a specific cultural and religious identity. Therein lies the antithesis that finds its higher unity in the capitalist system. The Jewish approach to economic life, according to Weber, must be understood in the context of the broader ethical and social framework provided by their religion. Weber emphasizes the role of Jewish law in regulating economic behavior; the intricate legal system developed by ancient Jewish scholars sought to ensure that economic activities were conducted ethically and justly. For example, laws concerning fair weights and measures, were aimed to prevent the exploitation of market life.

Marx’s essay in response to Bauer’s arguments against Jewish emancipation in Germany is really a springboard to discuss the nature of political and human emancipation. Marx contends that true emancipation requires the separation of church and state and then the abolition of all religious distinctions. This is one of many arguments Marx makes that anticipate Roberto Unger’s concept of “super liberalism,” a critique of liberalism that pushes beyond its traditional boundaries, reimagining how individuals can interact in ways that transcend established norms of personal autonomy, rights, and social organization to recover human solidarity.

In Unger’s view, traditional liberalism emphasizes individual rights, personal freedom, and legal structures to protect individuals from interference. However, he argues that liberalism in this conventional form fails to address deeper issues of social inequality, economic disparity, and the limitations imposed by rigid institutional frameworks. (This view is obviously inspired by Isiah Berlin’s observation of the distinction between “negative” and “positive” liberty, which was anticipated even earlier by Erich Fromm in his Escape from Freedom.)

In the nineteenth century, debates about Jewish emancipation were deeply entwined with broader questions about citizenship, statehood, and secularism. Marx’s intervention in this debate reflects his attempt to push beyond the immediate issue of Jewish rights to address the deeper, structural problems of capitalist society. His ultimate goal is the abolition of all forms of alienation, whether religious, political, or economic. Marx’s critique of Judaism can thus be seen as part of a broader critique of religion and its role in society, where he argues that political emancipation, the granting of equal rights within the state, does not equate to human emancipation, which is the liberation from economic and social constraints. For Marx, religion, including Judaism, represents an ideological barrier to true human freedom because it perpetuates a false consciousness that obscures the material realities of economic exploitation.