This essay follows up on last Monday’s essay on the Black Lives Matter (BLM) phenomenon. After rereading that essay, I felt it might be useful to apply some theory to more fully explain the dynamic the evidence indicates. Sheldon Wolin’s idea of managed democracy (also known as directed or guided democracy) highlights how corporate power shapes not only governance but also the nature of political dissent, ensuring that social movements remain within boundaries that reinforce rather than challenge the norms of neoliberal capitalism. This dynamic of co-optation transforms genuine populist resistance into commodified expressions of dissent that serve elite interests. Wolin’s theory is a useful frame in which to explain corporate co-optation and astroturf manufacture of (faux)social movements.

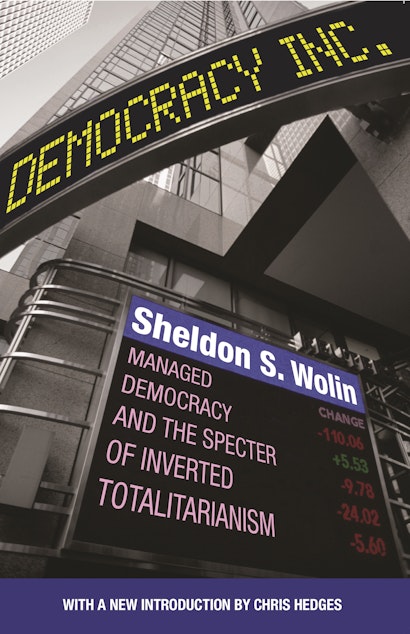

If you are unfamiliar with Wolin’s work, see Democracy, Inc.: Managed Democracy and the Specter of Inverted Totalitarianism. I highly recommend the book to you, but I hope that my application of his theory will be clear enough that you won’t have to read that book first to understand the analysis presented here. The core idea I am conveying is that, by absorbing the energy of movements seeking equality and justice, the system of inverted totalitarianism efficiently undermines the possibility of transformative change, leaving the structures of corporate control intact under the guise of supporting progressive causes.

To illustrate, before coming to more recent examples, we can apply the concept of managed democracy to understand the co-optation of organized labor under the New Deal, where corporate interests and a government that advanced those interests worked to redirect labor movements away from more radical aims and towards a controlled form of participation within the system. Under the New Deal, labor unions like the AFL and CIO were granted legal recognition and protections through legislation such as the Wagner Act, which guaranteed collective bargaining rights. However, the state, while seemingly empowering labor, contained it within the parameters of industrial capitalism, ensuring that workers’ demands would not challenge the broader structures of ownership and power. After the war, the CIA even used the unions to undermine popular democratic movements in Europe.

Thus the New Deal represents a moment where genuine labor resistance was transformed into a guided or managed force, one that ultimately stabilized and legitimized rather than threatened the capitalist order. By integrating labor unions into the system through institutionalized bargaining processes, the government effectively channeled labor’s potential revolutionary energy into reformist goals that aligned with the interests of corporate state power. This form of co-optation ensured that labor movements would focus on wage and benefit improvements within the existing system, rather than advocating for more transformative changes that could disrupt capitalist property relations or significantly alter the balance of power between capital and labor. This is the raison d’etre of progressive law and policy.

The appearance of democratic participation masked the underlying reality that corporate power remained more than intact but strengthened, as well as the administrative apparatus that advanced its interests. The labor movement’s co-optation under the New Deal effectively neutralized its more radical elements, turning the movement into a regulated entity whose influence was channeled through legal and political frameworks that benefitted elite interests, particularly those of large corporations. Instead of fostering a workers’ revolution or a movement toward socialism, organized labor became a tool for managing dissent, reinforcing neoliberal capitalism by containing labor’s aspirations within a system designed to maintain corporate dominance. To put this in a straightforward manner, the corporate state sucked the energy out of labor. This put the private sector union movement on a path to its present state—union density today stands at only six percent. At the same time, unions density among public sector employees, those who manage the affairs of the corporate state, stands today at 32.5 percent.

The corporate statism of the initial progressive period and the emergence of the United States as world hegemon laid the foundation for the emergence of neoliberalism in which individuals were reconfigured primarily as consumers rather than citizens, shifting focus from civic engagement to market participation. Under the New Deal, the federal government took on a central role in regulating markets, providing social safety nets, and promoting labor rights in response to the economic crisis of the Great Depression. This marked a significant departure from laissez-faire capitalism, as the state ostensibly sought to balance corporate power with social welfare through initiatives like Social Security, labor protections, and public works programs. The purpose of this intervention was to save capitalism and thwart socialism.

New Deal interventions entrenched the idea that economic growth and stability could be achieved through technocratic management of markets. As the state became deeply involved in regulating capitalism for the sake of the system itself, it also contributed to the commodification of everyday life, creating conditions where market logic could eventually permeate ever deeper into society. The individual was reimagined not as a citizen actively participating in civic life and democratic governance, but primarily as a consumer whose power lay in their purchasing decisions within the marketplace. This shift, the shift towards mass consumption to reproduce the circuit of capital represented a profound transformation in the role of individuals in society.

Neoliberalism, while criticizing state intervention in order to invert the hierarchy of power, built on the corporate-statist foundation of the New Deal to promote an economy dominated by large corporate entities. Under neoliberalism, the state’s role became one of facilitating market efficiency and protecting corporate interests rather than directly managing social welfare. Civic engagement, which was central to the New Deal’s progressive vision of democratic participation, i.e., a mechanism for integrating the individuals into the extended state apparatus, was replaced by a focus on individual market participation as the primary means of societal influence. It thus functioned to depoliticize the individual.

This shift from a citizen to a consumer orientation had far-reaching consequences. While individuals became masses trained and directed by the hegemonic apparatus, neoliberalism downplayed the importance of collective political action. The idea of freedom was redefined in market terms—freedom became the freedom to choose between products and services rather than the freedom to influence public policy or hold corporations accountable. This consumerist reconfiguration of American society eroded the public sphere, weakening civic institutions and undermining democratic participation. As individuals became more focused on their role in the economy as consumers, they disengaged from politics, which became increasingly dominated by corporate interests. This not only led to greater economic inequality but also to a more passive populace, less inclined to challenge corporate power or advocate for structural change in light of their own interests, while more easily mobilized for the interests of the corporate overlords.

As neoliberalism entrenched, public goods and services became increasingly privatized, and governance shaped by corporate interests, leading to a dominance of corporate logic in decision-making, transferring power that properly belongs to government and the people to corporations and financial institutions that prioritize profit over social well-being. Under these arrangements, the state becomes an instrument of corporate governance. Thus the corporatization of BLM described in my previous essays reflects how ostensibly radical or left-wing causes are negated by corporate interests. As I showed there, while BLM may have begun as a grassroots movement protesting police violence and systemic racism, it has received financial backing from large corporations and foundations. These endorsements align with corporate branding strategies that seek to appeal to social justice causes, enhancing their market appeal while avoiding substantive challenges to capitalism or structural inequality. This corporate support dilute a movement’s radical potential, steering its activism toward symbolic gestures or performative allyship rather than systemic change.

Other left-wing movements have faced similar trajectories, where their alignment with corporate and political elites in service to concentrated power compromises their ability to challenge the deeper roots of exploitation or inequality. Corporations embrace these movements not because of genuine solidarity with their aims, but because it allows them to harness activist energy to deflect criticism and bolster their own power within the capitalist system. In this way, what appears to be anti-capitalist or revolutionary rhetoric is absorbed and neutralized, serving the interests of those it ostensibly opposes. In addition to BLM, other movements that have been corporatized or coopted by corporate and political interests include the Women’s March, Pride, environmentalism, and the Me Too movement. I will briefly survey some of those cases so the reader can get a sense of the pattern.

The Women’s March was initially a grassroots protest against the inauguration of Donald Trump, the Women’s March received endorsements from major corporations and became entangled in mainstream political frameworks. The pussy hat, a pink, hand-knitted hat with cat-ear shapes on either side, became a symbol during the Women’s March, which began on January 21, 2017, the day after Trump’s inauguration. The hats were a protest of Trump’s remarks in a 2005 Access Hollywood recording, in which Trump referred to the way some women throw themselves at celebrities. The hats were an instantiation of defiant reclamation of a derogatory term in the same way that some blacks and gays reclaimed slurs used against them. Reclamation of derogatory terms referring to women express empowerment, resistance, and solidarity among those opposing misogyny and sexism. As the leadership of the Women’s March engaged with Democratic Party elites, it became clear that the movement focused on symbolic actions rather than challenging deeper systemic issues like class inequality and the globalization project which harms the material interests of women. (See The Appeal to Identity: Bad Politics and the Fallacy of Standpoint Epistemology.)

The LGBTQ+ rights establishment, particularly around Pride celebrations, has been heavily corporatized in recent years. Many large companies now sponsor Pride events and publicly support LGBTQ+ rights at the expense of gays and lesbians, as well as women and children. Corporate involvement sidelines demands for women’s rights in favor of marketable notions such as diversity and inclusion, reinforcing the neoliberal status quo without addressing the struggles of those who founded the movement and those who are affected by its corruption at the hands of gender ideology. As I have noted in the past (see The Function of Woke Sloganeering; Is the Madness Unraveling?), one reason corporations align with LGBTQ+ activism (aside from the growth industry of gender affirming care) is the rise of a social credit system that rewards companies for promoting gender ideology. Corporate rankings are influenced by the Corporate Equality Index (CEI), managed by the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), the largest LGBTQ+ advocacy group globally. HRC issues “report cards” for America’s top corporations based on how closely they adhere to the CEI’s guidelines, and companies that earn the maximum points are recognized as the “Best Place To Work For LGBTQ Equality.”

Beyond these incentives, other factors bring these entities together and intertwine them. Organizations like the Open Society Foundation and the Gay, Lesbian, Straight Education Network (GLSEN) contribute significant funding. ESG (environmental, social, and governance scores), a grading system that ranks entities from corporations to governments on their “social responsibility,” plays a powerful role here. Major investment firms like BlackRock back ESG, while groups like the World Economic Forum foster corporate alliances with organizations such as the HRC. The aim is to establish a social credit system that promotes transgressive ideologies like queer theory, creating niche markets around constructed identities and moving Western societies toward a global corporate governance model.

Global movements, such Fridays for Future climate strikes, inspired by Greta Thunberg, have seen corporate and institutional endorsement. Some environmental NGOs and campaigns have aligned themselves with major corporations that engage in greenwashing, i.e., promoting sustainability rhetoric while continuing environmentally harmful practices. Corporate support often shifts the focus from systemic critiques of capitalism’s role in environmental degradation and resource depletion to consumer-driven solutions like “green” products that don’t actually challenge the larger structures of exploitation and environmental destruction. (See my essay and talk The Anti-Environmental Countermovement. See also my award winning article “Advancing Accumulation and Managing its Discontents: The U.S. Antienvironmental Countermovement,” published in The Sociological Spectrum, as well as “The Neoconservative Assault on the Earth: The Environmental Imperialism of the Bush administration,” in Capitalism, Nature, Socialism.)

Initially a grassroots effort to highlight sexual harassment and assault, the Me Too movement was immediately embraced by Hollywood elites and corporate media. The pattern was highly similar to the BLM phenomenon I have described While it successfully brought attention to issues of gender-based exploitation and violence, its alignment with corporate media narratives depoliticized the movement, focusing on individual cases and high-profile abusers while avoiding systemic critiques of the industries that exploit labor and women’s bodies, especially in lower-income contexts. These movements, while powerful in their inception, often face the tension between maintaining their radical demands and the incentives offered by corporate and political alignment, which can steer them away from deeper systemic change.

* * *

Sheldon Wolin argues that in modern liberal democracies like the United States, a form of totalitarianism has emerged that operates differently from historical fascism. Instead of the state controlling corporations and society, with a dictatorial figure in command, corporate power subtly dominates and influences the state, leading to a more dispersed form of control that lacks the centralized authoritarianism seen in historical fascism. Wolin’s “inverted totalitarianism” describes a system where the state and corporate interests are deeply intertwined with the state functioning as a facilitator of corporate power rather than its master. Unlike fascist regimes where the state coerces corporate actors to serve its agenda, in this system, corporations and financial institutions shape and limit government policies. Political leaders and institutions increasingly serve corporate interests, and democratic processes are hollowed out, becoming mere rituals that disguise the reality of elite domination.

Wolin critique of the neoliberal order, where the market, media, and political systems operate in such a way that they perpetuate corporate control without overt authoritarianism, is an analysis for our time. This form of governance allows for significant corporate influence over public policy, including deregulation, privatization, and the weakening of democratic accountability, while maintaining the facade of democracy. A subtle form of domination, inverted totalitarianism avoids the visible repression associated with fascism, relying instead on economic coercion, media manipulation, and consumer culture to depoliticize the citizenry. In short, while classical fascism saw corporations working under a strong, centralized state, Wolin’s analysis inverts this relationship: corporations lead and the state follows, undermining democratic institutions and public accountability in a way that is more diffuse but equally dangerous. His interpretation reflects the rise of corporate oligarchy and technocratic governance, where the lines between public and private power blur, producing a system that serves corporate interests over those of the people.

Using Sheldon Wolin’s concept of inverted totalitarianism, the corporatization of social movements like BLM, Pride, and environmental activism can be seen as an extension of the neoliberal order’s ability to co-opt potential threats to its hegemony. These movements, which begin as grassroots calls for radical reform, are absorbed into the fabric of managed democracy, where dissent is neutralized through corporate sponsorship and alignment with political elites. Rather than suppressing opposition outright, the system co-opts it, turning once radical critiques into market-friendly slogans that leave the deeper structures of inequality untouched. As we approach the November 5 presidential election, it is important to carry this critique into the ballot box when making one’s decision. The Democratic Party is the party of inverted totalitarianism. (See Defending the American Creed.)