Update Friday, 8.16.2024. This clip of Douglas Murray.

* * *

“In Moulmein, in lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people – the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me. I was sub-divisional police officer of the town, and in an aimless, petty kind of way anti-European feeling was very bitter. No one had the guts to raise a riot, but if a European woman went through the bazaars alone somebody would probably spit betel juice over her dress. As a police officer I was an obvious target and was baited whenever it seemed safe to do so.” —George Orwell, “Shooting an Elephant” (1936)

“As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the River Tiber foaming with much blood.’ That tragic and intractable phenomenon which we watch with horror on the other side of the Atlantic but which there is interwoven with the history and existence of the States itself, is coming upon us here by our own volition and our own neglect.” —Enoch Powell, “The Birmingham Speech” (1968)

The dynamics of colonialism (and imperialism) can be understood as the incorporation of external areas into a global system of capitalist exploitation. In this dynamic, these regions are transformed into the periphery, or the Third World or Global South, where social surplus—in the form of cheap commodities appropriated through the exploitation (and superexploitation) of labor—is extracted to benefit the core, particularly the capitalist class and the managerial and professional strata that administer the corporate state.

In this global mode of production, the elite of the core countries, through their command of advanced industrial capabilities and military power, impose their dominance over peripheral regions. The periphery is systematically exploited, its resources drained to fuel the ceaseless capitalist accumulation that privilege a few at the expense of the many. This extraction process is often facilitated by local elites, or “colonial collaborators,” enriching themselves at the expense of their fellows. Thus, the local elites are co-opted into the colonial system, ensuring that the flow of resources to the core remains uninterrupted.

This dynamic also occurs internal to nation-states in the core. “Internal colonialism” refers to the systemic and often institutionalized exploitation of marginalized or minority groups within a dominant nation-state. Unlike external colonialism, where a foreign power imposes control over another region or people, internal colonialism manifests through the cultural, economic, and political subjugation of groups within a country’s borders. This involves the marginalization of indigenous cultures and the imposition of the dominant group’s language, social norms, and values. Internal colonialism often perpetuates socio-economic inequalities, where the dominant group benefits from the labor and resources of the oppressed communities, reinforcing a hierarchical structure that mirrors the dynamics of traditional colonialism.

Historically, religious ideology, particularly Christianity during the emergence and development of the capitalist mode of production, has been employed as a tool of ideological domination. The process of Christianization legitimized colonial rule and pacified colonized populations. Missionaries played a role in this process, promoting the colonial agenda under the guise of a “civilizing mission.” This ideological control mechanism complemented economic exploitation, embedding the colonial system more deeply into the social fabric of the periphery.

Through these mechanisms, colonialism reconfigured the mode of production in peripheral regions, subordinating it to the needs of the core. This system of exploitation and accumulation persists today, with the legacy of colonialism continuing to shape the economic and social realities of former colonies, maintaining their dependency and underdevelopment in the face of a dominant and thriving core. The wealth generated in the periphery is siphoned off, enriching the capitalist class and reinforcing the global hierarchy—a dynamic now often referred to as “globalism” or “globalization.” Globalization is marked by the offshoring of production and the importation of cheap foreign labor.

In the post-World War II period, advanced capitalist economies experienced a significant fall in the rate of profit, driven by rising labor costs, increasing competition, and the exhaustion of earlier waves of technological innovation. This decline posed a challenge to capitalists, who sought to restore profitability through various strategies. One approach was relocating production to lower-wage regions, especially in the Global South, where cheap labor could be exploited to reduce costs. Capitalists also pushed for deregulation and neoliberal economic policies, including tax cuts, the weakening of labor unions, and the privatization of public assets, to create more favorable conditions for profit-making. Financialization played a critical role as capital increasingly flowed into speculative activities and financial markets rather than productive investment. These efforts, while temporarily restoring profit rates, contributed to rising inequality, economic instability, and the entrenchment of a global capitalist system marked by deep structural imbalances.

China’s integration into the global economy represents a crucial development in the last several decades. After years of isolation, China embarked on a capitalist path in the late twentieth century, strategically aligning itself with global markets. By leveraging its vast labor force and adopting a state-capitalist model, China transformed into a central player in the global supply chain. While this allowed China to accumulate significant wealth and influence, it also entrenched the existing global economic order, concentrating power and capital in the hands of a few, as China itself became a formidable force within this hierarchy.

China’s rise as a global economic power was significantly fueled by the influx of foreign Western investment, which sought to exploit the country’s vast reserves of cheap labor. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, multinational and transnational corporations from the traditional capitalist core—historically the beneficiaries of colonialist and imperialist adventure and exploitation—shifted significant portions of their capital and technology to China. This migration was driven by the desire to maximize profits through lower production costs, enabled by China’s state-controlled labor market and favorable investment policies.

As a result, China became the world’s manufacturing hub, absorbing not only foreign capital but also advanced technologies that had previously been concentrated in the core. This transfer of resources and knowledge, while accelerating China’s development, also reconfigured global power dynamics, allowing China to emerge as a central player in the global capitalist system, even as the exploitation of its labor force mirrored the patterns of inequality established in earlier phases of capitalist expansion. Moreover, China’s vast apparatus of population control through censorship, surveillance, and social credit system provides a model for Western states in their ambition to control their populations. The United Kingdom is leading the way in the West.

Core areas of the West have undergone significant socioeconomic transformation amid these developments. Deindustrialization and economic stagnation have led to widespread poverty and social discontent, making these regions vulnerable to becoming the new periphery. The flow of cheap foreign labor into the capitalist core is reproducing the conditions of the Third World in the developed West. This shift is orchestrated by a transnational capitalist class that is reconfiguring capitalist flows and global labor, drawing populations from formerly colonized regions into the Western core. Migrants from externally colonized regions are integrated into the Western workforce (but not assimilated into the national culture with the doctrine of multiculturalism), often occupying low-wage and precarious jobs essential for sustaining the profits of the transnational capitalist class.

The West, thus, has become a new kind of periphery within its own borders, mapped onto the previous system, providing a reservoir of cheap labor and new market opportunities. This shift blurs the geographical distinctions between core and periphery while retaining the exploitative dynamics of colonialism. This is a new type of internal colonialism where the indigenous populations of the core are subordinated to colonial control now posed as globalism. These are the circumstances that native English, Irish, Scottish, and Welch find themselves in today.

The tools of ideological control have adapted to this new context. Islamization, through its strategic utilization by the transnational capitalist class, becomes a significant force in shaping social and cultural dynamics in the Western core. Capitalists leverage Islam to create divisions and maintain control over a fragmented workforce. The spread of Islam in the modern period is complemented by the rise of woke progressivism, an internal quasi-religious force serving corporate interests by promoting the doctrine of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

This dual ideological framework ensures that the new periphery within the West remains fragmented and focused on cultural conflicts rather than economic exploitation. This is not to say that the indigenous should not focus on the threat to cultural integrity and ethnic marginalization. It is to say that they must pay attention to what lies are the core of the fragmentation: the appropriation of the social surplus at their expense. The transnational capitalist class maintains its dominance, leveraging both external and internal forces to perpetuate a system of capital accumulation and labor exploitation. This perpetuates a cycle of dependency and underdevelopment, external and internal to the major nation-states of the international order, reinforcing the global hierarchy and sustaining the power and privilege of the capitalist class.

* * *

“That rifle hanging on the wall of the working-class flat or laborer’s cottage is the symbol of democracy. It is our job to see that it stays there.” —George Orwell

Enoch Powell, a member of the British Conservative Party, delivered his infamous “Birmingham Speech” on April 20, 1968. In that speech, later dubbed “Rivers of Blood” for its for its reference Virgil’s Aeneid, Powell expressed opposition to immigration and warned of dire consequences if immigration policies were not altered. He famously predicted that unchecked immigration would lead to community fragmentation, racial conflict, and social unrest. The speech was met with outrage because it evoked an apocalyptic vision of the future, suggesting that mass immigration would lead to racial conflict and bloodshed in Britain. Powell’s use of the phrase “foaming with much blood” and his comparison to the violent racial tensions in the United States were seen as racially divisive, inflaming racial prejudices.

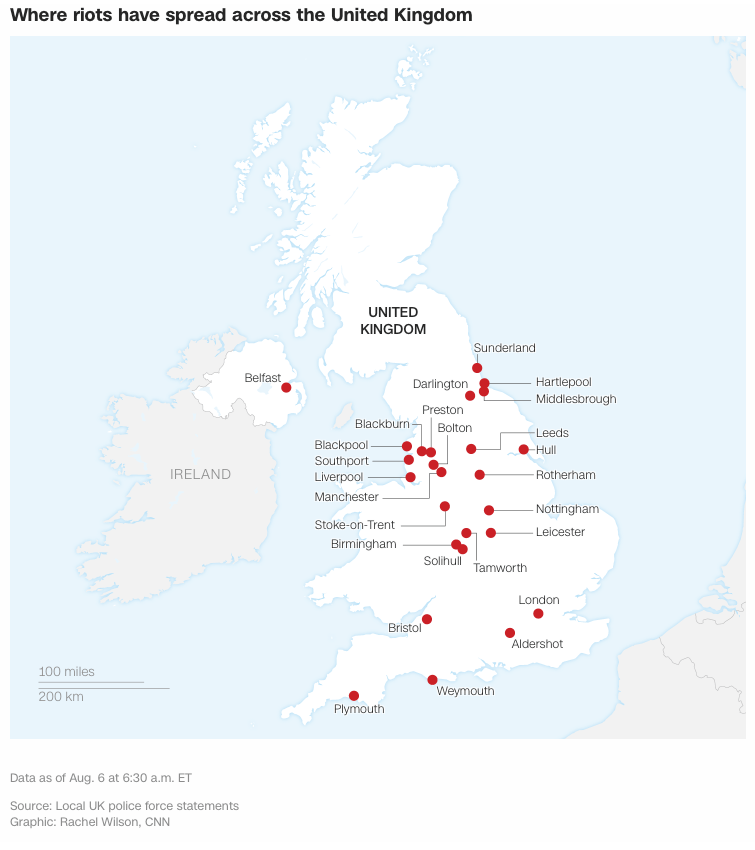

Nearly sixty years later, Powell’s prophecy fulfilled, the United Kingdom is experiencing another type of outrage: widespread resistance to colonization by the indigenous people there, primarily ethnic English. The English people, marginalized and overwhelmed by an influx of foreigners, disproportionately Muslims, and suffering a rash of criminal violence and terrorist attacks by them, have taken to the streets in a series of demonstrations, protests, and riots, echoing the struggles of indigenous populations across the periphery of the world system who resisted Western colonization in the past. However, the organic intellectuals of the corporate class don’t hear that echo. At least they pretend not to. And they are determined to make sure the people are either oblivious to it or don’t act on it if they’re not.

Academics, activists, politicians, and pundits, especially those on the left, have long celebrated anti-colonial resistance. These voices depict the history of Third World resistance to colonialism using terms that emphasize liberation, resistance, and self-determination. To highlight the struggle for freedom from colonial rule and oppressive regimes, opposition to domestic authoritarianism and external control, the right of peoples to govern themselves and make their own political decisions, they describe these struggles variously as “anti-colonial movements,” “liberation movements,” “resistance movements,” and “struggles for self-determination.”

The United Nations has consistently supported anti-colonial and post-colonial struggles, advocating for the rights of colonized peoples to independence, self-determination, and sovereignty. This stance became particularly prominent after World War II, during the wave of decolonization that swept through Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. The UN’s commitment to these principles was solidified in 1960 with the adoption of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, which asserted that all people have the right to self-determination and that colonialism should be brought to a speedy and unconditional end. The declaration emphasized the illegitimacy of colonial domination and the need for immediate action to support the transition to independence.

In addition to advocating for the end of colonial rule, the UN also recognized the right of colonized peoples to resist oppression, including the right to self-defense against colonial powers. This recognition was rooted in the broader framework of human rights and international law, which the UN sought to promote and uphold. The organization provided a platform for colonized nations and liberation movements to voice their demands for independence and to gain international support for their struggles. Throughout much of its history, the UN has maintained a clear commitment to the principles of anti-colonialism and self-determination, viewing the struggles of colonized peoples as an integral part of the broader quest for global equality and justice. This commitment has influenced international law and policy, reinforcing the rights of nations to pursue their own paths free from external control. Those in the West might ask whether they are free from external control.

These terms noted above used to describe these actions are intended to put colonial uprisings in a positive light, as well they should, focusing on the ideals of freedom, justice, and national sovereignty. UN and other international policies reinforcing the right of peoples to self-defense and self-determination are righteous. But if one were to use those same terms and same frame, and apply the same principles to explain, understand, and address the current situation in the United Kingdom, where the indigenous peoples of that island are rising up against the mass influx of foreigners organized by the transnational capitalist class and its colonial collaborators, colonization of the West by non-westerners, one would be marginalized and smeared. Without being able to explain why in a rational manner—without resort to original sin, blood guilt, and collective revenge—one would simply be told that the comparison is absurd. This would be accompanied by a lot of scoffing. The political economic development presented in the first section of this essay would be denied, since these facts identify and admit to the process by which the world population has proletarianized.

I want to emphasize that the point I am making is not analogical. The comparison occurs in the same world system, here in its late phase (hence the subtitle to this blog). And the double standard becomes even more obnoxious the more reality is described. For example, the movements and uprisings in the Third World were nationalist and populist in character, seeking to establish or maintain sovereign and independent nation-states, an obvious response to colonial domination, foreign intervention, and internal oppression. Third World nationalism is rooted in anti-colonial struggles where the indigenous fought to end colonial rule and achieve independence and self-determination. Nationalist movements sought to address economic inequalities by advocating for control over national resources and economic policies that prioritize the interests of the local population. But when nationalism and populism propel resistance to colonization and globalization in the core, those engaged in resistance are smeared as “bigots,” “fascists,” “nativists,” “racists,” and “xenophobes.”

The double standard is a blatant as the two-tiered justice system in the UK that I will come to in a moment. The UK demonstrations have been marked by fierce clashes with authorities, reflecting the deep-seated frustration of a population fighting to preserve its cultural identity and way of life. The imagery is like the uprisings seen in places like Algeria, India, and Zimbabwe, where indigenous peoples revolted against foreign domination (albeit more subdued). The sentiment on the ground is one of reclaiming sovereignty and pushing back against policies undermining the material interests of the indigenous English population. One of the flashpoints is the Islamization of the United Kingdom (and Europe more generally).

* * *

“National differences and antagonisms between peoples are daily more and more vanishing, owing to the development of the bourgeoisie, to freedom of commerce, to the world market, to uniformity in the mode of production and in the conditions of life corresponding thereto.” —Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848)

Marx and Engels famously declared in The Communist Manifesto that “the working men have no country.” By this, they meant that the working class are estranged from their organic nationalistic interests; the true ruling power in any capitalist society is not the state or the nation, but the capitalist class. The state serves primarily to protect and advance the interests of capital, often at the expense of the working class, regardless of national borders. This exploitation is not confined to any one country; it is a global phenomenon, inherent to the capitalist mode of production. When Marx and Engels said that the proletariat has first to defeat the national bourgeois, they were referring to the idea that the working class could only truly claim a nation or a state as their own through revolutionary struggle. By overthrowing the capitalist class, the proletariat could create a society where the state serves the interests of the many rather than the few.

I am not advocating for international socialism. What I am borrowing from Marx and Engels’ analysis is the insight that the working class is alienated from its national identity. The power structure estranges workers from self-rule and reduces them to mere instruments of capitalist production, disconnected from any genuine sense of national belonging. While Marx and Engels saw the solution in socialism and international solidarity, another interpretation can be drawn, particularly when considering indigenous populations and other culturally distinct groups under global capitalism. It was, after all, not the goal of anti-colonial resistance to force a world socialist system (this was the goal of the Soviet Union and Communist Chine) but to reclaim for the people control over their culture and local economies.

Whether in the geographical periphery or within internal colonial contexts, working people are similarly estranged from self-rule by the overarching power of global capitalism. Yet, unlike the cosmopolitan nature of the capitalist class, these communities retain a strong sense of cultural identity, ethnicity, and nationhood. For them, the concept of having “no country” is not just about economic exploitation but also about the erosion of their cultural and political sovereignty by global capitalist forces that prioritize profit over people. The problem with global capitalism is its tendency to homogenize and commodify cultures, erasing the distinctiveness of national and ethnic identities in favor of a global market system that serves the interests of a transnational capitalist elite—even while a strategy of multiculturalism is pursued to keep immigrants from assimilating with their host cultures. This system undermines the autonomy and cultural integrity of communities around the world, reducing diverse cultures to mere resources to be exploited or markets to be conquered.

The solution, therefore, lies not in a socialist revolution but in a return to a national system of producers, where the focus is on preserving and respecting the cultural integrity of all peoples in their homelands. This means recognizing and supporting the right of every ethnic group, indigenous community, or nation to govern themselves according to their own needs, traditions, and values free from the dictates of global capital. In this vision, national integrity is not about isolationism or antagonism between different groups but about mutual respect for the distinct cultural heritage of each nation.

Just as we respect the cultural integrity of ethnic groups in Africa or Asia, we should equally respect the autonomy and cultural distinctiveness of all peoples, whether they are cultural communities, indigenous populations, or national minorities within larger states—including European peoples. Why wouldn’t we if believed in equal treatment for everybody? This approach promises a world where the diversity of cultures is celebrated and protected, and where economic systems are aligned with the values and needs of the people they serve, rather than subordinated to the imperatives of global capital. Are the indigenous peoples of the First World not also entitled to this?

There is nothing in this vision that precludes any people from adopting the superior elements of the cultural systems of other national groups, for example the Enlightenment principles such as feminism, liberalism, rationalism, science, and secularism found in the First World. One might suppose that Enlightenment values should be coercively imposed on non-Westerners, but however much the globetrotting capitalists have claimed that this was their goal (“modernization,” they called it), what they were really after was the value of the labor there and the natural wealth embedded in its territory. But what should be vigorously resisted is the introduction of backward cultural elements from the Third World and the destruction of Enlightenment principles in the West.

Why are the indigenous peoples of Africa and Asia admired for their populism and nationalism, encouraged to pursue anti-colonial resistance, their right to struggle recognized by the United Nations recognized, even celebrated, but when Europeans do the same, they are smeared and suppressed? It’s cannot be because Europeans were once the colonizers. This obscures the dynamic of world capitalism. The English didn’t colonize India—the English capitalists did. It also supposes a quasi religious doctrine in which the living are responsible for the evil deeds of their ancestors, a modern-day version of original sin that prompts blood guilt to be settled through collective violence against the indigenous peoples of Europe. The double standard is founded upon anti-White racism.

* * *

“I think that we’ve got to see that a riot is the language of the unheard.” —Martin Luther King, Jr. (1967)

As the streets of Birmingham, London, Birmingham, and other major cities in the United Kingdom are filled with impassioned citizens rallying against the new form of colonization, those who extolled the virtues of colonial resistance by the indigenous peoples of the colonized lands now turn against the colonial resisters at home. These are the colonial collaborators I spoke of earlier. And, from the capitalist standpoint, a better clique of them of them is now in charge. The Labour Party is the party of the transnational corporate elite. The pivot to authoritarianism after the election on July 4, 2024, has been swift and comprehensive.

During the George Floyd protests in 2020, marked by significant property damage and interpersonal violence, the government and many political leaders employed the rhetoric of “social justice,” emphasizing the importance of addressing systemic racism and supporting peaceful protests. More recently, following the October 7, 2023 Hamas terrorist attacks targeting Jews, pro-Palestinian protests in the UK, particularly in London, were massive and often violent. The police response was one of restraint, with the Metropolitan Police making arrests here and there and forming cordons around the protests to manage the crowd and maintain public order. In stark contrast, the indigenous revolt against the new colonialism, tagged as “far right,” “neo-Nazi,” etc., has been violently suppressed by the same political figures.

This disparity in framing reveals how the government addresses different forms of social unrest for political purposes—to advance the new colonial project. The George Floyd and pro-Palestinian protests, aligning with progressive social justice causes, received and continue to receive a sympathetic, often encouraging framing, while the current protests, which challenge immigration policies and highlight concerns of national identity, are quickly dismissed as extremist.

The reality is that the UK government, as many of is European counterparts, has been facilitating immigration to the country through various policies and programs aimed at attracting workers and seeking refugees (see Culture Matters: Western Exceptionalism and Socialist Possibility). Immigration has been a significant and contentious issue in the UK, with policies ostensibly aimed at addressing labor shortages, fulfilling international humanitarian obligations, and promoting diversity and economic growth, but which drive down wages, disorganize communities, enlarge the welfare rolls, and increase criminal violence. The facilitation of colonization has led to debates and tensions around national identity, resource allocation, and social cohesion. The current protests reflect a segment of the population’s dissatisfaction with these policies. The influx of immigrants threatens their cultural heritage, economic opportunities, and national integrity.

* * *

“For it is the condition of his rule that he shall spend his life trying to impress the ‘natives’ and so in every crisis he has got to do what the ‘natives’ expect of him.” —George Orwell, “Shooting an Elephant” (1936)

George Orwell discusses his experiences in the colonial police in his 1936 essay “Shooting an Elephant.” This essay reflects on his time as a police officer in Burma (now Myanmar) during the British colonial period. In the essay, Orwell recounts a specific incident where he felt compelled to shoot an elephant to maintain his authority and the expectations of the local population, despite his personal reluctance. The piece is a powerful commentary on the complexities and moral dilemmas of colonial rule and the impact it had on both the colonizers and the colonized. (Orwell’s 1934 novel Burmese Days offers further insights into his perspectives on colonialism and his experiences in Burma. This novel draws upon Orwell’s experiences as a colonial police officer, providing a critical portrayal of British imperialism and the effects of colonial rule.)

The colonial police were central to maintaining the grip of colonial powers over their territories. Their role was primarily to enforce order and uphold the colonial laws, which were often designed to benefit the colonizers and suppress the local population. These police forces operated with a mandate to prevent any form of dissent or resistance. They were the enforcers of a system that prioritized the extraction of resources and the maintenance of colonial dominance. The police acted as the visible arm of colonial authority, monitoring gatherings, patrolling streets, and swiftly quelling uprisings and protests. They were instrumental in implementing policies that restricted the movement and freedoms of the colonized, using intimidation and violence to ensure compliance. Their presence served as a deterrent to rebellion and as a means to protect the interests of the colonial elite. The police were not just enforcers of law, but also symbols of oppression. They embodied the colonial state’s authority, their actions reinforcing the hierarchical structure that kept the colonized subjugated and the colonizers in power.

Today, the role of the “colonial” police is transformed but retains its essence of control and suppression. In this new context, where the West becomes the new periphery within its own borders, the function of the police is reimagined to suit the needs of the transnational capitalist class. The police are tasked with ensuring the stability of a system characterized by economic inequality and social tension. In this time, the police serve to enforce the new status quo. They manage the discontent arising from deindustrialization and economic stagnation, where a significant portion of the population finds itself in precarious, low-wage sectors. Crucially, the enforcement of order involves not only traditional policing activities but also the suppression of protests and movements that challenge the economic and social disparities perpetuated by the transnational capitalist class.

In the 2014 Guardian article “Chief constable warns against ‘drift towards police state,’” we can see concerns for the police state date at least as far back as a decade (of course, they date further back that than). Sir Peter Fahy, chief constable of Greater Manchester, warned, that in the battle against “extremism,” officers were being turned into “thought police.” He said police were being left to decide what is acceptable free speech in the state’s efforts to combat against “radicalization.” But he was not saying that the police should not have a role in suppressing speech. It’s the academics, politicians, and others in civil society who have to define what counts as extremist ideas, he said. Indeed, he stressed that he supported new counter-terrorism measures recently unveiled by the government, including bans on alleged extremist speakers from colleges. But the lines need to be made clear or it would be decided by the security establishment, so-called “securocrats,” including the police and security services.

* * *

“There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork.” —George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four

The UK’s surveillance system is one of the most extensive and sophisticated in the world. This system, ostensibly designed to ensure public order and national security, encompasses a vast network of CCTV cameras, data collection, and digital monitoring. However, its implementation and effects have raised concerns about a two-tiered justice system that treat different populations unequally. The UK’s surveillance network includes millions of CCTV cameras, which monitor public spaces around the clock. This infrastructure is supplemented by digital surveillance tools, including the monitoring of online activities, social media, and telecommunications. The stated goal is to prevent crime, terrorism, and maintain public safety. Yet, the surveillance disproportionately targets certain groups and enforces a biased administration of justice.

A notable aspect of this perceived two-tiered system is the differential treatment of native-born populations and immigrant communities. Native-born individuals who express concerns about immigration or critique policies associated with it often find themselves under scrutiny. In some cases, they face legal consequences for speech deemed “discriminatory” and “hateful.” Online platforms, monitored by authorities, are quick to censor and punish individuals for content considered offensive or inflammatory, particularly if it critiques immigration policies or multiculturalism. In contrast, immigrant populations, especially those from marginalized or minority backgrounds, enjoy a different level of response from the state. Protests and even riots led by these communities are met with leniency and a more restrained approach by law enforcement. This disparity is said to be attributed to various factors, including the desire to avoid accusations of racism, maintain social cohesion, and uphold a commitment to diversity and inclusion—in other words the hegemony of the corporate state.

Thus the state’s differential response to dissent is shaped by broader ideological commitments to multiculturalism and anti-racism (i.e., anti-white bigotry). While these commitments are ostensibly said to protect vulnerable communities and promote social harmony, the rhetoric is designed to obscure the double standard. Native-born populations rightly come to feel that their grievances are disregarded or unfairly punished. This functions to deepen the sense of alienation and resentment by those whose concerns and needs are marginalized in favor of accommodating immigrant communities. In this context, the surveillance system becomes a tool not just for maintaining public order but for enforcing a particular social order.

* * *

I will close with this. Powell’s speech led to his dismissal from the Conservative frontbench. Many viewed his rhetoric as alarmist and xenophobic. To be sure, some supported his views (probably more than would admit it), arguing that he was highlighting real concerns about integration and social cohesion. But others condemned him for fear-mongering and promoting racism and on their judgment the country took no action. With the unfolding of history, the world can see that Powell’s concerns were valid. Millions of indigenous peoples on the island Powell called home can see it everyday. Better that he was never proven right. But the past cannot be altered (except through Orwellian means). So the question now is what to do about. Electing a Labour government was certainly not a wise choice.