There’s nothing wrong with this. Political economy is one of my areas of expertise in my sociology PhD. I had great professors—Asafa Jalata and William Robinson. It was definitely a Marxist program. I was appointed to my present position because of my other expertise, criminology. But my approach is a synthesis of these fields yielding the political economy of crime and punishment. Students get a lot of critical and historical economic thought in my courses, which are organized around the materialist conception of history, which is what Marx called his version of the dialectical method. Donald Harris and I work in the same tradition.

Kamala Harris was born in 1964. She and her mother and sister left her father in 1970. I don’t know how much time they spent together then or after the breakup. It doesn’t appear that Kamala knows the first thing about political economy (or much else, to be blunt about it). However, the tactic of guilt by association is truly a ratty one, in this case on two levels, the first involving the manufacture of significance about happenstance of blood relation (a child does not pick her parents), the second the presumption that one’s status as a Marxist professor is somehow untoward and disqualifying.

On this latter point, the critique of political economy is necessary to avoid ideological glorification of capitalism. Anticommunism has two purposes: first, defending individual liberty against totalitarianism (George Orwell’s cause); second, preventing the delegitimizing of capitalism by claiming that is a just and reformable system (the cause of the progressive). In the second sense, Marxism is not the economic theory of a new mode of production, but rather a critique of the capitalist mode of production. Karl Marx had very little to say about socialism and communism except to criticize those individuals and movements who identified as such.

Here is Marxist economic thought and political project in a nutshell: The dialectical process in concrete history is the working out of internal contradictions elevating the system to a higher unity by resolving contradictions while retaining the superior features of the previous productive modality. This higher unity does not eliminate all contradictions and creates contradictions of its own. This is why there is history. What Marx sought to do was develop critique-as-praxis so that the higher unity might be steered towards greater equality for the masses, who had been proletarianized with the emergence of the capitalist mode of production, with the eventual elimination of class antagonisms that had marked all previous history after primitive communism (the original state of mankind). At the philosophical level, communism was man coming home to himself, since social segmentation is the source of alienation, which involves self-estrangement, and communism is the elimination of class antagonisms.

I agree with Marx here, but because socialism has been a disaster for people, I no longer identify as a one. Moreover, communism from the Marxist standpoint, understood as a classless and stateless social organization (stateless in as much as it eliminates the oppression of the administration of people), has never existed anywhere in human history on the higher technological plane (which capitalism is rapidly raising). Marx didn’t specify communism because he eschewed utopian thinking. I am in agreement with Christopher Hitchens (Orwell’s biographer), who remained a Marxist until his death, that capitalism has more work to do before the conditions will be such that we can think about moving to a different productive modality. After all, Marx himself said that social revolutions don’t occur until the conditions are ripe for it.

Marx put it this way in his 1853 The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.” Then, in his 1859 A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, on the subject of revolutionary transformation, he writes, “In studying such transformations it is always necessary to distinguish between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production, which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the legal, political, religious, artistic or philosophic—in short, ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out. Just as one does not judge an individual by what he thinks about himself, so one cannot judge such a period of transformation by its consciousness, but, on the contrary, this consciousness must be explained from the contradictions of material life, from the conflict existing between the social forces of production and the relations of production.”

Brilliant stuff. This is the materialist conception of history. Here’s the point: “No social order is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed, and new superior relations of production never replace older ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework of the old society.” Marx continues: “Mankind thus inevitably sets itself only such tasks as it is able to solve, since closer examination will always show that the problem itself arises only when the material conditions for its solution are already present or at least in the course of formation.”

In my view, corporatism is the late stage of capitalist development. But there is no way of knowing how long the end game will last. Things don’t act right when they’re dying, and we certainly see the signs of its death throes in present conditions. We’re in a period of watch and wait—and the darkness of the approaching upheaval is ominous. The global elite know this, and this is why they are steering the economy towards a global neo-feudal order where proletarians are turned into serfs and managed on high-tech estates. They seek these ends to protect their wealth and privilege.

As Michael Parenti told us, the rich has ever wanted on one thing: everything. “There’s only one thing that the ruling circles throughout history have ever wanted—all the wealth, the treasures, and the profitable returns; all the choice lands and forests and game and herds and harvests and mineral deposits and precious metals of the earth; all the productive facilities and gainful inventiveness and technologies; all the control positions of the state and other major institutions; all public supports and subsidies, privileges and immunities; all the protections of the law and none of its constraints; all of the services and comforts and luxuries and advantages of civil society with none of the taxes and none of the costs. Every ruling class in history has wanted only this-all the rewards and none of the burdens.”

Given that they control all the major institutions of modern society, and given the level of disorganization and false consciousness among the proletariat, it is most likely neofeudalism will be our fate. The promise of liberation with the unraveling of the present system will more likely be an even more profound totalitarian system (we already live under conditions of emergent inverted totalitarianism), this time on a world scale.

Orwell warning in Nineteen Eighty-Four is terrifying: “There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always—do not forget this, Winston—always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.” It may be that we live in a cage with a degree of creature comfort to match our lowered expectations. In either case, it will be a state of unfreedom.

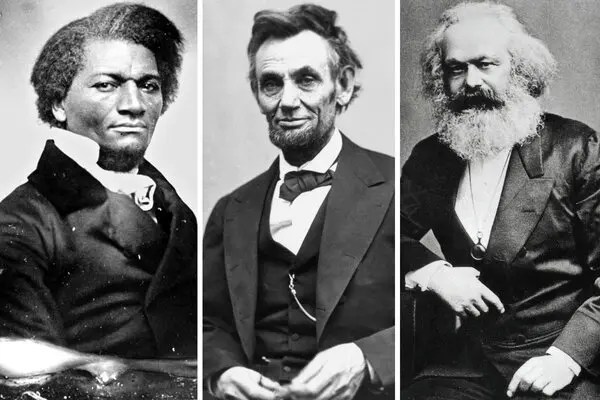

But I want to leave you with hope. Frederick Douglass, one of the three great republicans of the nineteenth century (the others being Abraham Lincoln and Karl Marx), noted that “the limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.” Douglass is telling us that the power and extent of tyranny is determined by the level of tolerance and endurance of the oppressed people. Put another way, tyrants can only exert as much control and oppression as the oppressed allow. Douglass’ is alerting us to the agency and potential power of the oppressed. If people who are subjected to tyranny refuse to accept their suffering and actively resist, then they can limit or perhaps even overthrow the tyrant’s power. The endurance of oppression by the people is a measure of the tyrant’s control; when the oppressed reach a breaking point and no longer endure the oppression, they can catalyze change and potentially bring an end to tyranny.

Here is Donald J. Harris’s faculty page at Stanford.

https://web.stanford.edu/~dharris/papers.htm

And over fifty years ago, Monthly Review Press had Harris write an introduction for their edition of Nikolai Bukharin’s The Economic Theory of the Leisure Class.

https://web.stanford.edu/~dharris/papers/'Introduction‘,%20Economic%20Theory%20of%20the%20Leisure%20Class.pdf

Here is a better link to Donald Harris’ introduction to Bukharin’s The Economic Theory of the Leisure Class.

https://tinyurl.com/yj2c49td