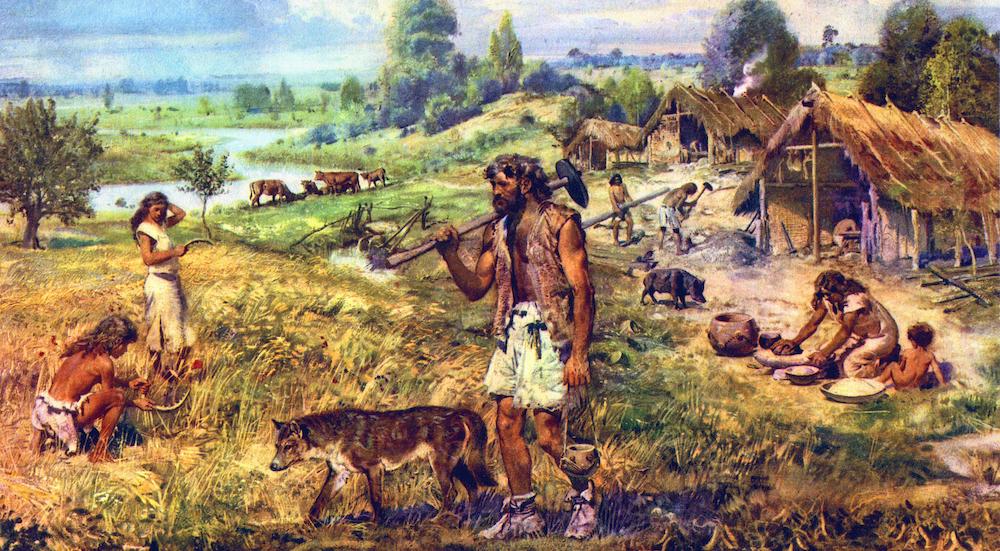

Gender roles are influenced by the natural sexual division of labor, rooted in biological differences and reproductive necessity. Roles have traditionally been organized around sexual dimorphism, which means that males and females have phenotypic differences that organize themselves into overlapping trait distributions, with men typically undertaking tasks requiring greater physical strength and endurance, such as defense, heavy labor, and hunting, while women often assume roles linked to childbearing and nurturing, such as caregiving, domestic duties, and gathering. This division stems partly from practical considerations of reproductive capacities, as women’s childbearing and breastfeeding functions necessitate proximity to home and offspring.

Stereotypes, the result of typification—the process of categorizing and generalizing (abstracting) individual experiences or entities into broader types based on shared characteristics—is innate and often advantageous. From an evolutionary perspective, the human brain has developed the ability to categorize and simplify complex information as a survival mechanism. This cognitive shortcut, known as heuristics, enables humans to make rapid decisions about resources and social interactions, enhancing their chances of survival, both individually and as a species. By grouping individuals and situations into broad categories, stereotypes reduce cognitive load and allow for more efficient processing of information and a greater likelihood of correct action. To be sure, there is considerable error, for example the risk of type I error. Nonetheless, it is better to presume that the rustling in the bush one hears behind him is an approaching apex predator. Likewise, humans are not always correct about the gender of others; for the most part, the gender detection module is quite reliable and advantageous.

While these roles were practical in early human societies, and to in many ways continue to be in modernity, they have also often been rigidly codified into social norms and expectations that lead to gender stereotypes that can limit individual potential and reproduce inequities. Modern societies increasingly recognize the flexibility and shared capabilities of all individuals, regardless of gender, and thus promote a more equitable distribution of social roles and responsibilities. There has been much progress in these efforts.

At the same time, the intrinsic differences that result from natural history remain relevant, as men often exhibit greater athletic prowess due to higher levels of testosterone, muscle mass, and physical strength. This biological predisposition contributes to the overrepresentation of men in physically demanding activities. Additionally, evolutionary factors and social conditioning have led to a higher prevalence of men in violent behaviors and roles associated with aggression and defense, reflecting both historical survival strategies and ongoing societal influences issuing from the sexual dimorphism inherent in the species.

Gender stereotypes vary significantly across cultures and historical periods, shaped by diverse social norms and situations. In the past, culture was predominantly shaped by collective beliefs and practices, reflecting shared values and social organization. Gender stereotypes served as a system of beliefs and practices that helped communities maintain cohesion and stability, emerging from roles individuals assumed based on biological differences and practical needs. Cultural norms surrounding gender roles evolved through consensus and adaptation to local conditions, fostering a diversity of gender expressions across societies.

However, the rise of the culture industry has seen corporations exert significant influence over cultural production, shaping gender stereotypes and societal norms to align with commercial interests rather than community values. This industrial-strength influence, encompassing advertising, entertainment, and media, often perpetuates narrow and superficial portrayals of gender, embedding oversimplified images in societal norms and reinforcing them through repetition. This continuous exposure to stereotypical representations can lead to their internalization, making them seem natural and eternal despite their inaccuracies and irrelevancies. (See Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann’s 1967 The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge for a comprehensive treatment of this dynamic.)

The freedom for individuals to express themselves in any manner they choose, regardless of gender, is fundamental to human dignity and well-being. Gender expression encompasses behavior, clothing, hairstyle, voice, and other characteristics traditionally associated with masculinity or femininity. Allowing individuals to explore and present themselves authentically fosters a more tolerant and diverse society, challenging outdated elements of gender roles and enriching our cultural landscape. As I have revealed here on Freedom and Reason, coming of age in the 1970s (I graduated high school in 1980), the practice of so called “gender bending” was common place and I participated in it. Moreover, as a rock musician on the 1980s, makeup and traditional women’s clothing were a major element in stage presentation. I participated in that as well.

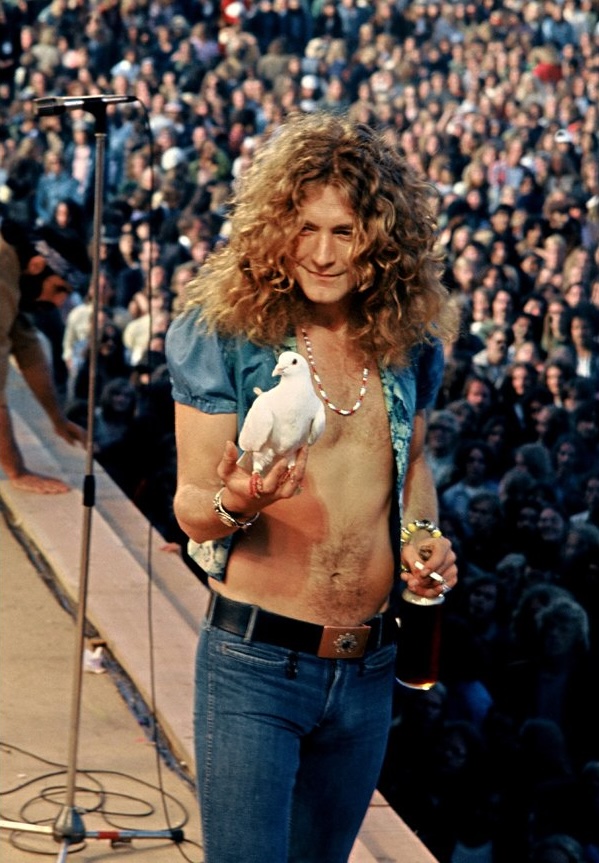

Beyond the queer politics of gender expression understood in terms of “identity,” the evolution of gender expression more broadly in modern societies reflects a dynamic shift towards greater individual freedom and diversity. Today, women comfortably embrace fashion traditionally associated with masculinity, such as wearing pants, minimal makeup, and sporting short hair, challenging old stereotypes and asserting their right to express themselves however they wish. Similarly, men’s fashion has also seen significant transformation, influenced by popular culture movements since the 1960s, again, seen in music genres like hard rock, where long hair, makeup, and more effeminate clothing remain commonplace. This cultural evolution underscores a broader acceptance of fluidity and diversity in gender presentation, breaking away from rigid norms imposed by traditional gender roles.

Perhaps, like me, the reader sees a paradox in all this. How is it that talk about fashion in terms gender presentation confuses gender in terms of biology with the social roles organized around it, as well as with the expression of gender stereotypes? This confusion is intentional. Consider the trans woman who presents in a stereotypically feminine manner to pass socially (if this is the intent rather than autogynephilic desire)? Is this not a limiting construct, one reinforcing narrow definitions of womanhood? Why should the man who wishes to be woman look like exaggerated culture industry expression of femininity? These expectations have been subject of feminist critique, which advocates for freedom from restrictive gender norms and the right of individuals to define their gender identity and expression on their own terms, free from the pressures of societal stereotypes.

From the gender critical standpoint, one of the primary critiques of gender ideology and gender-affirming care is that it reinforces gender stereotypes rather than liberates individuals from them. Feminism has long fought for the recognition that a woman’s worth and identity are not defined by traditional markers of femininity such as wearing makeup, donning dresses, or possessing certain physical attributes like large breasts. The biological reality of being a woman, feminists argue, does not necessitate adherence to culturally and historically contingent standards of femininity. Therefore, a woman can express herself in a myriad of ways that do not conform to stereotypical gender norms, yet she remains unequivocally a woman due to her biology.

In contrast, the gender critical perspective views trans women’s pursuit of traditionally feminine appearances—such as wearing makeup, dresses, seeking feminized facial features, and enhanced breasts—as an embodiment of traditionally stereotypical femininity or stereotypes constructed by the culture industry. This reliance on external markers of gender identity contradicts the feminist objective of detaching womanhood from these very stereotypes. Furthermore, the assertion that gender identity is valid regardless of anatomy introduces a paradox: if a woman can have a penis, as gender ideology claims, why must a trans woman adopt stereotypically feminine traits to be recognized as a woman?

Beyond the fallacy of gender identity as an innate and internal subjective sense of one’s gender, focus on external transformation to align with gender identity reinforces of the very stereotypes that feminists have sought to dismantle. In this view, gender affirming care, which includes medical and surgical interventions to achieve a more traditionally feminine or masculine appearance, perpetuates the notion that adhering to these stereotypes is necessary for one’s “true gender identity” to be recognized and validated (affirmed). Since the many and most fundamental differences between men and women cannot be erased through gender affirming care, the practices associated with the practice result not in an actual transition to different genders but in simulated sexual identities that reify gender stereotypes.

Seeking feminized or masculinized features through gender affirming care perpetuates culturally, historically, and commercially bound notions of what it means to be a woman or a man. By emphasizing external markers of gender, such as fashion, makeup, or physical traits like breasts, gender-affirming care realizes these stereotypes in the form of an altered body. This, from the gender critical perspective, is contrary to feminist aims of liberating individuals from restrictive gender norms imposed by the patriarchy. The practice of aligning one’s external appearance with their imagined gender identity (imagined because identity is not what a thing thinks of itself but what it is in fact) is viewed as a reification of gender stereotypes, solidifying abstract and arbitrary things as concrete and necessary components of one’s gender identity.