President Trump gave his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention of the day before yesterday. He spent several minutes at the outset talking about the attempt on his life. Between the day a sniper’s bullet pierced his ear (on Saturday a week ago) and his speech on Thursday, a massive doxxing campaign emerged, with pro-Trump forces, most prominently Chaya Raichik, who runs Libs of TikTok, calling out those who publicly expressed regret that the shooter, identified by the FBI as Thomas Matthew Crook, missed his target. Many people have expressed that sentiment on social media and in street interviews. Some of them have been fired from their jobs for expressing it.

I oppose the doxxing and firings for the expression of opinions. I condemn what Raichik and others are doing. US citizens should be free to express their point of view, and given what they believe about Trump, their opinion is reasonable. Don’t misunderstand. What those who wish Trump dead believe is not true. But if it were, then their wish is understandable. Former congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard put it well when she tweeted “The assassination attempt on President Trump is a logical consequence of repeatedly comparing him to Adolf Hitler. After all, if Trump truly was another Hitler, wouldn’t it be their moral duty to assassinate him?” Moreover, wouldn’t it follow that there would be many people who would celebrate the assassins and regret their failures?

If one could go back in time and kill Hitler, would the assassin be a hero or a villain? The answer is obvious. In 1939, Georg Elser, a German carpenter, planted a bomb in the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall in Munich where Hitler was giving a speech. The bomb exploded, but Hitler had left the venue early, narrowly escaping the assassination. In an assassination attempt orchestrated by a group of German military officers led by Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg (Operation Valkyrie) in 1944, conspirators planted a bomb in Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair headquarters. The bomb exploded, killing four people and injuring others, including Hitler. Colonel von Stauffenberg, along with Henning von Tresckow, Hans Oster, and Ludwig Beck, are celebrated today as anti-fascist heroes.

To be sure, the vast majority of those wishing Trump dead would never take it upon themselves to do what Crooks did. They have others do their dirty work. But the fact that they wish Crooks hadn’t missed reveals the effect of the steady diet of anti-Trump rhetoric comparing the president to Hitler and warning that a second Trump term would be the end of democracy. The problem here isn’t the desire itself. It’s the historical comparison. Trump is not Hitler. Indeed, he is the opposite. Whereas Hitler dismantled democratic-republican structures and put in their stead a corporate state and technocratic rule, Trump campaigns on deconstructing the administrative state and reclaiming the classical liberal values that underpin the constitutional republic the Founders envisioned. Hitler sought perpetual war. Trump seeks peace. Etcetera. The danger isn’t individuals prepared to act patriotically. The danger is false narratives that feeds stochastic terrorism. To be sure, the free speech right protects such narratives. But those who weave them bear moral responsibility for their consequences.

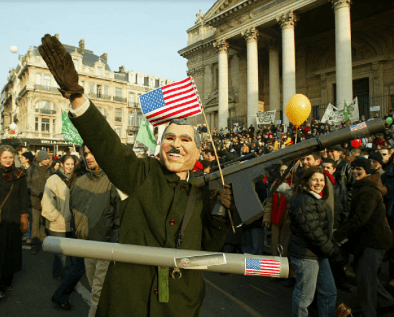

This is not the first time we have been through something like this, that is suggestions that the problems of the police state and warmongering can be solved with a bullet. During George W. Bush’s presidency there were numerous demonstrations and protests where comparisons were drawn between Bush and Hitler. This juxtaposition was used by opponents of Bush’s policies, particularly in relation to the Iraq War and the Patriot Act.

I opposed both the Iraq War and the Patriot Act (taking to the streets to protest, participating in teach-ins at my university, and publishing essays and book chapters highly critical of the neoconservative consensus), but the comparison of Bush to Hitler represented a bad analogy, since fascism had by that time had taken the form of inverted totalitarianism wherein there was no need for dictatorship. Sheldon Wolin made the compelling case for the new totalitarianism in Democracy, Inc.: Managed Democracy and the Specter of Inverted Totalitarianism, published in 2008. Wolin has long warned about democracy’s vulnerability to being subverted by the increasing intertwining of corporate and state power. (For more about Wolin’s thesis, as well as other work concerning the enduring attributes of fascism see my July 6 essay Celebrating the End of Chevron: How to See the New Fascism.)

In 2005, the Lawton Gallery at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, the university where I teach, featured an art exhibition by graphic artist Al Brandtner titled Axis of Evil: The Secret History of Sin. The ideas were conveyed in the form of US postage stamps. One notable piece depicted the burning World Trade Center with the caption “Blame God.” But that’s not the piece that got the attention of the Secret Service. The artwork in question featured a page of stamps portraying President George W. Bush. The background displayed the red-and-white stripes of the American flag, while a hand with a gun pointed at Bush’s temple emerged from the right border. The bottom of the stamps read “Patriot Act.” Brandtner’s attorney was questioned by Secret Service agents when the piece was included in a traveling exhibit of more than a hundred mock postage stamps.

The chancellor of UW-Green Bay at the time, Bruce Shepard, censored that artwork. the Secret Service had gotten to him. A book in which the piece appeared, along with other items from the exhibit, was made available to the public, on a stand, opened to the page, but the piece itself was not allowed to hang on the wall with the others. In an email, Shepard expressed his concerns, stating, “The advocacy of assassination is something I view as neither abstract nor theoretical. It happens, it is real. I further believe that the one piece of concern very reasonably can be seen as expressing advocacy of assassination.” Shepard elaborated on his decision in the email, saying that not censoring Brandtner’s work would mean using taxpayer money to potentially encourage the assassination of President Bush. “It is a question of whether this campus will use publicly provided resources for what, very reasonably and by many, will be construed as advocacy of a most violent and unlawful act,” Shepard explained.

For his part, Brandtner tried to have it both ways. He claimed that his artwork was not intended to promote assassination, but his explanation under questioning by The Badger Herald indicated otherwise. “The chancellor was taking the point of view that it’s advocating assassination. I didn’t see it myself as I was threatening, and I really didn’t see it as a real scenario. I don’t expect people to heed the call and do something so crazy.” The phrase “heed the call” makes the point rather dramatically—so what is the call? He explained that the provocative nature of his work was encouraged by the curator of the exhibit, Michael Hernandez de Luna, who, Brandtner said “was flat-out adamant that the work we or anyone submitted to him was hard-hitting and ball-busting, that kind of stuff.” Brandtner continued: “I was just trying to use Bush as sort of a target. I was trying to define that Patriot Act somewhere and turn that around and redefine it.”

Brandtner bragged that the censorship had unintentionally increased interest and publicity for his work. Brandtner said that the controversy had unexpectedly given him a significant political voice. “I’ve never been able to express my political views in a very coherent way,” he said. “I’m a guy that’s just trying to make a living as a graphic artist and all of a sudden some artwork that I’ve done has propelled me into the middle of an argument.” He stated that his artwork was an extreme illustration of his frustration with the Bush administration, referencing political assassinations by self-proclaimed patriots throughout history. The stamps, according to Brandtner, represented “sort of a wishful thinking about the Bush Administration in general that they would just be gone.” In other words, Brandtner’s Patriot Act was a death wish.

Shepard’s actions sparked protests and a panel discussion on what free speech, academic freedom, and censorship mean on a college campus. My colleague Carol Emmons, a well-respected installation artist, participated and sobbed as she reflected on the state of freedom on our campus. This was the same chancellor who not only failed to defend me from efforts to derail my tenure but who wrote me one of the nastiest letters I have ever received from an administrator. And here he was censoring an artist at a public university. He defended himself by saying that the piece was viewable, as he could not bring himself to remove the book. But in the end he bent to the government censor in the form of the Secret Service.

As I watched Carol regain her composure, my mind went to Stephen King’s The Dead Zone. Johnny Smith awakens from a five-year coma with psychic abilities—he can touch objects or people and see into their past or future. Dr. Sam Weizak, a Holocaust survivor, is the neurologist who treats Smith after he awakens from his coma. Weizak contemplates what he would have done if he had the chance to assassinate Adolf Hitler before World War II. Their discussion explores the ethical dilemmas Smith faces as he grapples with his powers of insight, highlighting the complexities of intervening in history.

Smith meets Greg Stillson, an ambitious politician campaigning for a seat in the US House of Representatives. Shaking hands, Smith foresees Stillson becoming a dictator and instigating a nuclear war. Smith makes an attempt on Stillson’s life during a political rally. The assassination attempt fails. However, Smith’s actions inadvertently lead to Stillson’s downfall. In the process of defending himself, Stillson grabs a child to use as a human shield, and a photographer captures this moment. The resulting public outrage over Stillson’s cowardice and lack of integrity destroys his political career. Smith is mortally wounded. He dies satisfied that he changed the course of history.

When my recollection of King’s novel began, I had thought about using it as a preface to a question inspired by it. But I realized that it would take too long to set up the question without looking like I agreed with the sentiment expressed by Brandtner’s artwork. Although I loathed George Bush, I did not agree that assassinating him would solve any problems.

We may never know whether Crooks believed he was solving a problem. We will never know whether he knew he had failed at his task if indeed that’s what it was. We do know two things, however. Unlike Stillson, Trump rose courageously from the deck and led the crowd in a chant of “Fight! Fight! Fight!” If Crook’s goal was to stop what he believed was the second coming of Hitler, then he failed spectacularly. Secondly, if Crook believed that Trump represented the second coming of Hitler (we know millions Democrats do), then he was moved by a false narrative, a narrative that endangers the life of a man whose patriotism is fearless.

Experiencing attempted cancellation at a public university highlights the troubling reality of authoritarian impulses in contemporary discourse. I know. It happened to me—twice (see The Snitchy Dolls Return.) The desire to see someone fired for their opinion undermines the foundational principles of academic freedom and open dialogue (see Republicanism, Free Speech, and the Illiberal Impulse). In an environment meant to foster diverse perspectives and critical thinking, such attempts at silencing dissent and opinion not only threaten individual livelihoods but also erode the intellectual rigor and democratic ethos that universities should uphold. This experience underscores the urgent need to defend free expression and resist authoritarian tendencies that seek to stifle debate and diversity of thought in academic institutions.

I disagree with Jennifer Collins’ opinion, but I defend her right to express it—and condemn those who are attempting to get her because they disagree with her. The free speech right must include the freedom to express regret that an assassination attempt failed. Wishing somebody were dead is not an uncommon wish. Others have the right to criticize somebody who expresses such regret (or any other). But to want to see the speaker/writer fired for having expressed it is an authoritarian impulse. To be sure, the authoritarian has the right to express his desires to see people cancelled. Likewise, the rest of us also have the right to criticize him for it. If we are not authoritarians, then we criticize him, but we do not contact his place of employment and attempt to get him cancelled. This is the difference between authoritarians and liberals, the latter doesn’t seek to harm a person with disagreeable opinions.