This past March, I published an essay Passive-Aggressive and the Depoliticization of Antagonisms through Medicalized Jargon in which I argued that psychologists in the service of the capitalist and managerial classes have effectively medicalized class conflict as a depoliticizing maneuver, delegitimizing the reason workers resist exploitation and oppressive control by psychologizing their motive, i.e., by dissimulating the social antagonisms that lie at the heart of the capitalist mode of production. In today’s essay, inspired by a conversation with clinical psychologist and addition expert Gloria Hamilton (Professor Emeritus Middle Tennessee State University), I explore a similar construct, that of “pathological demand avoidance” (PDA), that appears to serve a similar function and represent an instantiation of the same corporate state desire to control individuals.

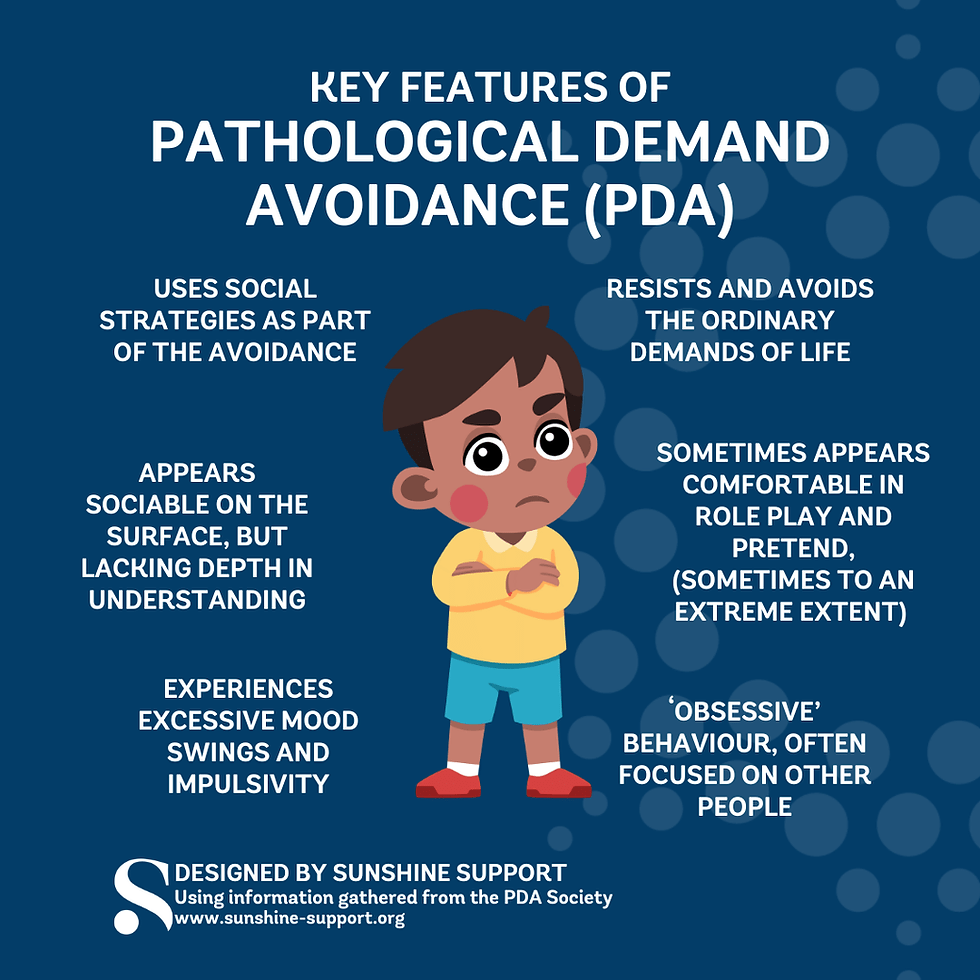

The construct originates in the work of Elizabeth Newson in the 1980s. A child psychologist, Newson (working with others) observed a distinct set of behaviors in some children that differed from the more typical presentations of what is now called autism spectrum disorders (ASD). She coined the term to describe a profile characterized by an extreme avoidance of everyday demands and expectations and a need to control situations and interactions. Individuals with PDA exhibit high levels of anxiety and are often driven by the need to feel in control, ie., an intolerance of uncertainty. This can manifest in a range of behaviors such as pretending to be unwell (the sick role) and social manipulation to avoid demands (see The Field of Dreams of Childhood Trauma).

The avoidance in PDA is not limited to challenging or significant demands but can extend to everyday tasks and interactions, making it difficult for persons with the condition (assuming it as such for the moment for purposes of description) to engage in regular routines or comply with requests from others. This often results in heightened levels of frustration and anxiety for both the individual and those around them, including family members, caregivers, and educators. Crucially, unlike other autism profiles, individuals with PDA may display more socially strategic behaviors, which can sometimes mask their underlying difficulties.

In their work proposing this for inclusion in the DSM, “Pathological demand avoidance syndrome: a necessary distinction within the pervasive developmental disorders,” Newson, Le Maréchal, and David, describes individuals with PDA as autistics who exhibit an unconventional and superficially high “degree of sociability,” which facilitates social manipulation as a significant skill. Manipulation, which is typically defined as the artful or unfair control others for personal advantage, carries connotations of insidiousness—subtle, to be sure, yet harmful. Thus, labeling someone with PDA implies that their social skills are perceived only in terms of their utility for manipulating situations to their advantage, potentially disregarding genuine social difficulties and underlying autistic traits. (Are we instead describing somebody with a Cluster B personality disorder who is also on the autism spectrum?)

From a sociological perspective, the concept of PDA can be interpreted as a manifestation of individual resistance to the overbearing demands imposed by bureaucratic and corporate systems. In highly bureaucratic societies, individuals are subjected to constance and numerous demands, expectations, and regulations. These demands can be seen as an extension of corporate social control, shaping individuals’ behavior and imposing a strict conformity to organizational norms. PDA typically manifests in early childhood, suggesting that bureaucratic elements may not be the primary factor but an exacerbating force; however, the early introduction of children into corporate society, starting with school at age four and often even earlier with day care, with early child care and education becoming increasingly corporatized, creates an environment where children are subjected to constant demands and structured routines from a very young age.

The term “corporatized” refers to the process by which organizations, institutions, or activities adopt the characteristics, practices, and operational styles of corporations (see my recent essay Are Progressives Smarter Than Everyone Else? which contains a lengthy treatment of the social logic corporate bureaucratic arrangements and its effect). This includes a focus on efficiency, profitability, standardization, and hierarchical management structures. When applied to settings like childcare and education, corporatization conveys the emergence and elaboration of environments that prioritize cost-effectiveness, measurable outcomes, and streamlined processes, oftentimes coming at the expense of individual needs and personal interactions.

For children predisposed to PDA, the highly demanding and regulated environment of corporate bureaucracy expands, elaborates, and intensifies the inventory of avoidance behaviors. In the case of late-onset PDA, then these “symptoms” (attitudes and actions) could very well represent ordinary resistance to overbearing control by individuals not prepared for such experience. The constant pressure to conform and comply with organizational norms in these settings will naturally heighten anxiety and avoidance behaviors, trigging the need for greater control, and exacerbating the symptoms of PDA. Thus, even if the origins of PDA lie within the individual, or at least some individuals, the corporatized nature of early childhood care and education can significantly influence the expression and severity of PDA behaviors.

When individuals exhibit behaviors that avoid or resist these demands, the system tends to medicalize their attitudes and actions. Psychiatrists and other medical professionals frame the behavior as a psychological issue rather than a rational response to the stress and pressure of bureaucratic expectations. Like the psychiatric category of passive-aggressive criticized in that March essay, this medicalization serves to depoliticize and individualize what is essentially a form of social resistance. The medical diagnosis of PDA can thus be seen as a way to pathologize behaviors that challenge or disrupt the smooth functioning of bureaucratic systems. By labeling these behaviors as pathological, the system shifts the focus from the social and structural causes of the behavior to the individual’s psychological state. This shift allows the system to maintain its legitimacy (thus authority) and control, as it portrays the issue as a personal deficiency rather than a critique of the broader social structure. The effect is to normalize oppressive relations and stressful conditions.

In essence, then, the avoidance behaviors seen in PDA can be interpreted as a micro-level form or personal manifestation of resistance to macro-level social demands. Individuals may consciously or intuitively reject the constant pressures of compliance and conformity imposed by bureaucratic and corporate organizations. The medicalization of such resistance transforms a potentially political and social critique into a personal medical issue, thus neutralizing its subversive potential and reinforcing the status quo. That PDA lacks a clear and distinct diagnostic criteria, and the fact that there is ongoing debate within the professional community about its validity as a separate profile within the autism spectrum, raises suspicions among sociologists (at least this one), that in many cases this may not be a genuine medical diagnosis, at least not without some elements that exist independent of the bureaucratic environment, the elements of which (efficiency, calculability, predictability, productivity, uniformity) have become ubiquitous. We might consider how PDA might have looked in premodern societies and, more importantly, whether it appeared at al. What is more, in the psychological community, the question of whether this is really oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) raises the further question of whether ODD is itself a psychiatric category or yet another instantiation of the medicalization of personal resistance to bureaucratic circumstances.

A useful critical perspective comes from social psychologists who propose the concept of “rational demand avoidance” (RDA). Replace the word “control” with “agency,” “autonomy,” “independence,” “self-determination,” that is, swap the need of the individual to control their environment with the individual need to resist irrational and external controls, and one comes to a very different conclusion. Damian Milton and Richard Woods, both autistic individuals who challenging stereotypes and advocate for inclusive practices that respect autistic ways of being, have suggested RDA for this reason. They argue that what is labeled as PDA may actually be a rational response to excessive and unreasonable demands placed on individuals, particularly in highly structured and overbearing environments and demands. From their standpoint, behaviors associated with PDA are not pathological but instead logical reactions to maintain autonomy, resist overwhelming external pressures and associated stressors. They advocate for a more nuanced understanding of demand avoidance, reconceptualizing it as a potentially adaptive behavior in response to oppressive or overly demanding circumstances, rather than as a developmental disorder.

From a critical sociological standpoint, therapies designed to help individuals prepare for life in a world dominated by corporate bureaucratic control are at the same time a form of indoctrination preparing them for inclusion in a highly controlled environment. This perspective suggests that therapy does not simply address individual needs but implicitly accepts and reinforces the structures of overregulated society. Therapeutic approaches that emphasize collaboration, negotiation, and reducing perceived demands aim to manage behaviors associated with PDA by building trust and reducing anxiety, creating environments where individuals feel heard and understood. However, these methods suggest a need for broader societal redesign. The changes proposed for supporting individuals with PDA—fostering empathy, flexibility, and a reduction in rigid demands—would benefit everyone, indicating the need for a societal shift towards more humane and less controlling structures. This reimagining of therapeutic principles as a blueprint for societal reform challenges the acceptance of an overly bureaucratized world, promoting a vision of a more inclusive, understanding, and flexible society.

Therefore, however we are to conceptualize this phenomenon, it is clear that the therapeutic principles used to support individuals with PDA—collaboration, negotiation, and reducing perceived demands—point to the necessity of broader societal changes. As C. Wright Mills tells us in his 1959 The Sociological Imagination, and Thomas Szasz in his landmark 1960 essay “The Myth of Mental Illness”), the problems that plague individuals often suggest that the current societal structure, which imposes rigid demands and prioritizes efficiency over individual well-being, might very well be fundamentally flawed. These are instead, Szasz says, “problems of living.” Embracing these therapeutic principles on a larger scale could lead to a more humane and flexible society that benefits everyone, not just those with PDA. This rethinking of societal norms aligns with the idea that therapy should not just prepare individuals for an overly controlled world but should also advocate for a world where such extreme control is made unnecessary.

* * *

There are two other features of PDA I haven’t addressed. I am still thinking about these and how they might represent resistance to overbearing social expectations. The first is the feature of individuals appearing especially comfortable in role play and pretend. This differs from typical role-playing and imaginative escape in notable ways. While all children engage in imaginative play as a natural part of development, for those with PDA pretend a distinct purpose of avoiding demands placed upon them. Thus individuals with PDA exhibit a more strategic use of role play to avoid or negotiate social situations. Heightened ability to immerse the self in roles is a coping mechanism, allowing the individual to navigate social expectations in a way that feels safer or more manageable.

The second feature involves obsessive behavior focused on other people, which manifests as an intense preoccupation with individuals or specific social dynamics, sometimes to the exclusion of other interests or responsibilities. Unlike general curiosity or interest, the focus in PDA can become all-consuming, leading to persistent thoughts, questions, or behaviors directed towards others. This behavior can impact relationships and daily interactions, as the individual’s attention may fixate on particular people or relational dynamics. This obsessive focus may fluctuate based on perceived threats or personal goals, often serving the individual’s need for control or understanding within social interactions.

Feel free to comment with ideas about how these fit with my critique of corporate bureaucratic relations and the attempt by medical professionals to pathologize the ways individuals negotiate the overbearing conditions these relations represent, especially in light of individual differences.