“Political language—and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists—is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” —George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language” (1946)

Words have meanings—the underlying sense or significance—and usages—how they are employed in language. When people say that meanings and usages change over time, they’re making a trivial observation. The relevant and substantive questions are how fast is the language shifting and why? Normally, language evolves slowly. Here there may be some sort of natural-history-like logic at work. However, when a language changes rapidly, a project to alter the meaning system to some end—be it commercial, ideological, political—is indicated.

For centuries, the words “gender” and “sex” existed in the English-speaking word as synonyms. The concept of gender was used by scientists in studies of animals and plants to refer to reproductive biology. It wasn’t until later, much later, only recently, in fact, and not everywhere, that the project to alter mass understanding of men and women by changing the meaning and usage of “sex” and “gender” appeared. At its back, the project enjoyed the power of the academy (eventually even 4k-12), culture industry, mass media, and the medical-industrial complex. Dictionaries dutifully revised definitions. Everything changed in a unified way. That sort of thing doesn’t happen by accident.

Yesterday, I recounted on Freedom and Reason an X (Twitter) exchange with users, unwittingly perhaps, committed to obscuring the meanings of sex and gender (see “The phantoms of their brains have got out of their hands”). I was told, as if I didn’t know, that not all of the world’s languages past and present are gendered. That fact does not erase gender, of course. “How could propagation of the species in those cultures occur if there were no gender?” I asked. After all, plants have gender, I noted (I’m fond of noting this, as regular readers know), and plants have no culture or language. The flower contains a stamen (male organ) or pistil (female organ). It’s rather straightforward.

When I say that “sex” and “gender” are synonyms, I mean they are interchangeable. However, the term sex is used in a few different but related ways. Sex, like gender, may refer to the female and male of a species of plant or animal. Sex is also an action, i.e., how organisms reproduce. When an X user said he had never heard of anybody wanting “to have gender” with another person, I mocked him, but he was onto something. Apart from its use as a grammatical subclass (not entirely, of course), gender refers to reproductive anatomy, but can also be a verb in the sentence: “He gendered her correctly.” As I noted in yesterday’s blog, sex can also be a verb, as in “The farmer sexed his chickens,” i.e., he determined (not assigned) their gender. Like plants, chickens have genders. The male chicken we call a “rooster.” Although he could never list them on his social media profiles, the rooster has “he/him” pronouns. The female chicken is a “hen.” She has “she/her” pronouns. The hen is the one who lay the eggs.

It is a relatively easy matter to show that gender is a term in natural history, used by scientists to describe the reproductive anatomy of plants and animals. However, none of those who push the queer propaganda line will make any effort to enlighten themselves about it. They may run across the evidence supporting my argument, but they would never produce it themselves, opting instead to repeat the assertion that “while sex refers to this, gender refers to that,” or treating gender as if it were a category appropriated from grammar and that’s just fine as long as it furthers the political-ideological agenda of decoupling of sex from gender. Appropriating the category to use as a synonym for sex is entirely inappropriate for precisely the same reason.

In her article “Gender in Plants,” published in 1998 in Resonance, ecologist Renee Borges writes, “Recent studies have shown … that many hermaphrodite plants do not contribute genes equally through male and female function to the next generation. Individual plants range from being relatively more or less male to relatively more or less female. This finding coupled with the modular and indeterminate nature of plant growth and reproduction led to the important perspective that sex expression in plants is a quantitative phenomenon, i.e. it depends on the relative proportion of reproductive units of both sexes within an individual plant.” Did I note the name of the article? Yes, “Gender in Plants.”

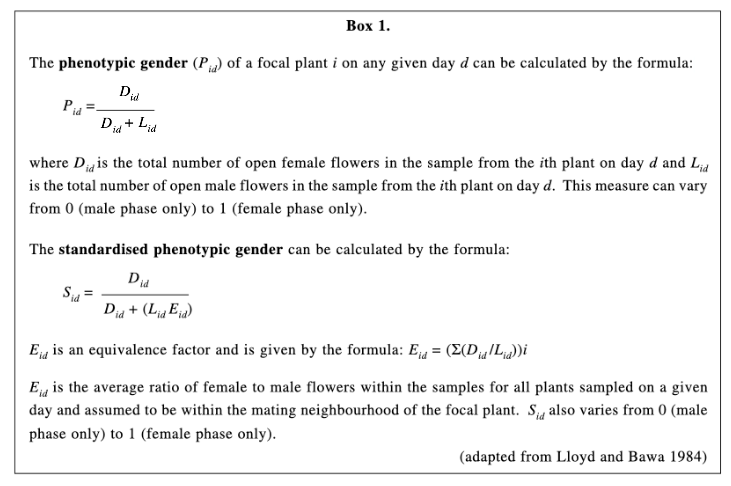

“From this point of view,” Borges continues (the bold lettering appears in her text), “the term plant sex denotes the various mating systems of plants such as monoecy or androdioecy [i.e., sex as action] while the term plant gender refers to the relative representation of male and female function in the entire plant [i.e., reproductive anatomy and gamete size]. The phenotypic gender of a plant then signifies the relative proportions of male and female reproductive units in terms of flowers, pollen or ovules at any given time on the plant (see Box 1). The functional gender of a plant is its relative contribution to the next generation via the male and female functions in terms of how many offspring it has sired or how many seeds it has matured.” This lines up well with the history of these two terms, with “sex” denoting action or activity and “gender” noting kind or type.

I am including Box 1 from Borges’ article so readers can see the mathematical precision with which gender can be determined. Note that the equations are adapted from a text published in 1984 by Lloyd and Bawa. This would be David Graham Lloyd, a fellow of the Royal Society in London who made landmark contributions to the field of plant reproduction, especially his work studying plant gender. Gender is a precision term used in natural science—a fact trans activists refuse to accept or admit.

As readers can see for themselves, gender is not a social construction in the sense that it is culturally or historically variable or exists as an internal subjective sense of one’s gender that may be at odds with one’s gender. Gender is an objective matter, a term denoting the reproductive anatomy and gamete size of plants and animals. This is universally true, and this truth is not changed by postmodernist deconstructionist jargon or the commercial language of so-called gender medicine.

In 2018 article in Plant Biology, Pannell and Arroyo write (and here I will bold the letters for readers), “The extent to which individuals in a hermaphroditic population deviate from the expected gender of 0.5 can be appreciated in terms of their ‘phenotypic’ quantitative gender, or in terms of their ‘functional’ gender (Lloyd 1980). A plant’s phenotypic gender describes its allocation of resources to one sexual function relative to the other, while its functional gender reflects not so much its investment strategy, but its actual success as a male versus female parent.”

“Thus,” they continue, “plants that transmit more of their genes to progeny via their pollen than their ovules will have a male‐biased functional gender (i.e., a gender < 0.5). This bias may reflect a male‐biased phenotypic gender or sex allocation, but it may also simply be the outcome of who mates with whom, i.e., because the individual happens to be a better than average sire. Similarly, a hermaphrodite may be functionally more female than male not through an adapted sex allocation strategy but simply because its seed production is less strongly pollen‐limited. Hermaphrodite individuals that vary in their floral morphology, such as those in distylous populations, may also vary in this way in their phenotypic and/or functional gender.” Note that the authors remind the reader that when they’re talking about gender they’re using it synonymously with sex in the case of phenotypic gender.

Before readers remark upon the gender fluidity of plants, a phenomenon anomalous in mammals, they should first admit that they cannot talk about hermaphroditic individuals without first acknowledging the gender binary. An individual cannot be both genders without two genders existing a priori. Moreover, before objecting to my well-known counter that the clown fish, which can change genders, is not relevant to the question of whether humans can, my point here is that gender is a scientific term native to natural history. I would no more argue that sapiens are plants than I would that they are clownfish, even though all three categories are gendered organisms.

In 2007, Thomas Meagher, in the pages of the Annals of Botany writes (here, too, I will bold some text), “Evolutionary models of gender evolution have, of necessity, posited genetic effects that are relatively simple in their impacts. Emerging insights from developmental genetics have demonstrated that the underlying reality is a more complex matrix of interacting factors. The study of gender variation in plants is poised for significant advance through the integration of these two perspectives. Bringing genomic tools to bear on population-level processes, we may finally develop a comprehensive perspective on the evolution of floral gender.”

Meagher recognizes that the use of gender in this way is an old one. “The general theme of the present review is evolutionary transitions among different gender states. One reason that the evolution of gender polymorphism has attracted so much attention is that the diversity of gender states found in flowering plants represents many independent evolutionary events. Moreover, gender variation in plants has a long history of scientific investigation. Darwin (1877) was among the first to focus attention on gender variation and its evolution in plants.”

But it’s even older than Darwin. The word “gender” entered the English language from Old French in the late fourteenth century. Originally, it was used to refer to “kind,” “sort,” or “type,” and was derived from the Latin word “genus,” meaning the same. Our species sapiens is the only extant species of the genus Homo. Our species, like all animal species, in turn contains two genotypes, female and male, which almost always present as corresponding phenotypes (derived from the Greek phaino, which means “appearance”). You may have noticed that the word genotype bears some resemblance to “gender” and “genus”—and “gene,” as well Indeed, genos is Greek for offspring or race, which indicates “kind,” “sort,” or “type.”

Thus when asking, “What gender is this animal?”, you are asking what kind, sort, or type of animal this is. Is it a dog or a cat? It’s can’t be both. (You don’t have to be a biologist to know that.) If there is a language that lumps house pets such that there is no separate word for different kinds, it doesn’t mean they are the same kind of animal. It just means that the language is constrained in such a way as to make it more difficult to differentiate between two things that look alike in some ways, or have a similar relationship to human, but aren’t alike in other ways. We expect that the answer given to this question in a culture with a language permitting accuracy and precision would be appropriate to the species or breed in question. “This is a dog.” “What kind of dog?” “A sheep dog.” “Is it a boy or a girl?” “How would I know? It can’t tell me.” “Does it have a dick?”

As I have noted in past essays, the use of “gender” in botanical contexts can be traced back to at least the seventeenth century, and possibly even earlier. As used in plant biology today, yesterday’s botanists used it in the same way: to differentiate between male and female reproductive organs or structures in plants. Its synonym “sex” entered the English language from Old French in the fourteenth century, as well. It’s derived from the Latin word sexus, which refers to the state of being either female or male. So we are back to kinds, sorts, and types. Thus, in its earliest usage in English, “sex,” like “gender,” denoted biological differences between female and male types of animals, particularly in terms of reproductive anatomy and functions. This usage remains prevalent today, particularly in scientific and medical discourse.

Let’s return to the common objection made by those ignorant of biology and history that gender is a noun subclass. I have had individuals insist that gender as currently used by queer theorists and the medical industry was derived from there and never referred to reproductive autonomy. They never bothered to ask themselves the obvious question, What does gender as a noun subclass do in language? It is really entirely arbitrary? Why do the words “feminine” and “masculine” appear when discussing gender as a grammatical category? Do they look like they might be related to these words: “female” and “male”? Indeed. The Latin femina means “woman” The Latin masculus means “male.”

But, to make sure, let’s consult a blog called Gender World, subtitled Musings of a woman who happens to be transgender, which I take to mean that a man wrote the entry (although elsewhere the individual claims to be “gender non-conforming,” a construct that once again requires the a priori existence of the gender binary, but could go either way gender-wise). In the entry “What is Gender?” (written in 2018 or early 2019) the blogger does the typical amateur move of uncritically turning to Merriam-Webster, reporting that gender as “a subclass within a grammatical class (such as noun, pronoun, adjective, or verb) of a language that is partly arbitrary but also partly based on distinguishable characteristics (such as shape, social rank, manner of existence, or sex) and that determines agreement with and selection of other words or grammatical forms.”

Did you catch the word “sex” in there? The blogger also shares definition 2a, the synonym “sex” defined as “the feminine gender,” b clarifying gender in this usage as denoting “the behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with one sex” (clarifying later on that “trait” is defined as an inherited characteristic). With what sex would “the feminine gender” be associated? That’s a question that’s only difficult for those who cannot define what a woman is. There is a part c to the 2 definition, one I am not sure would have been included then, namely the term “gender identity,” inserted without definition (because it’s not an actual thing). That the blogger didn’t share this part despite its political centrality in gender ideology strongly suggest that Merriam-Webster added the term after the blog was posted.

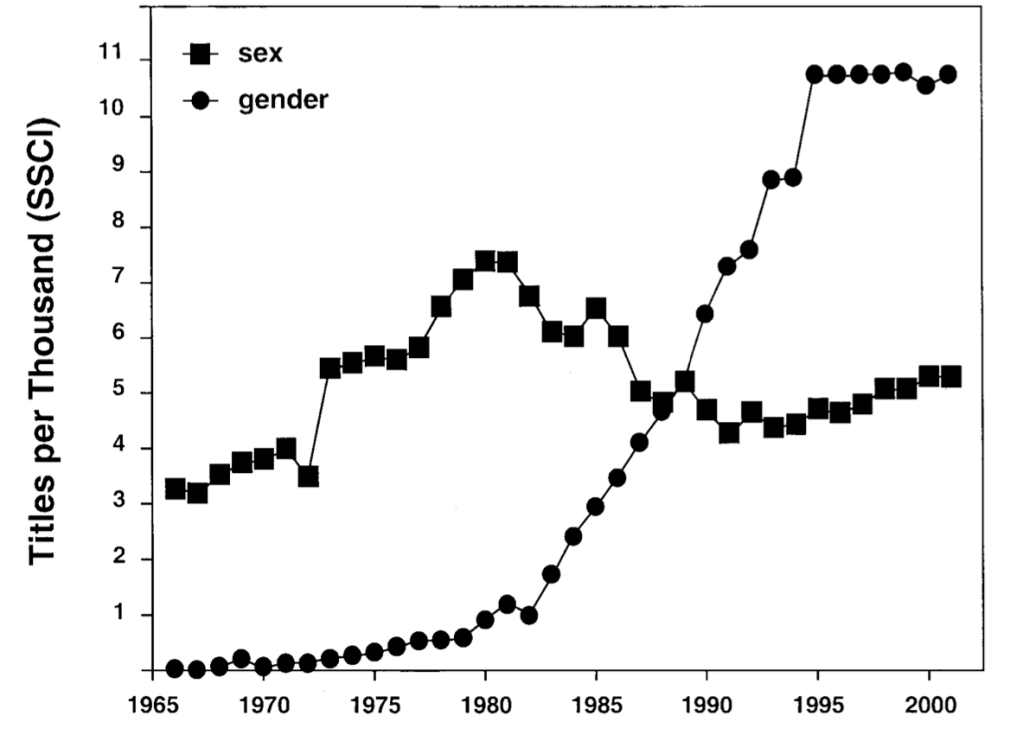

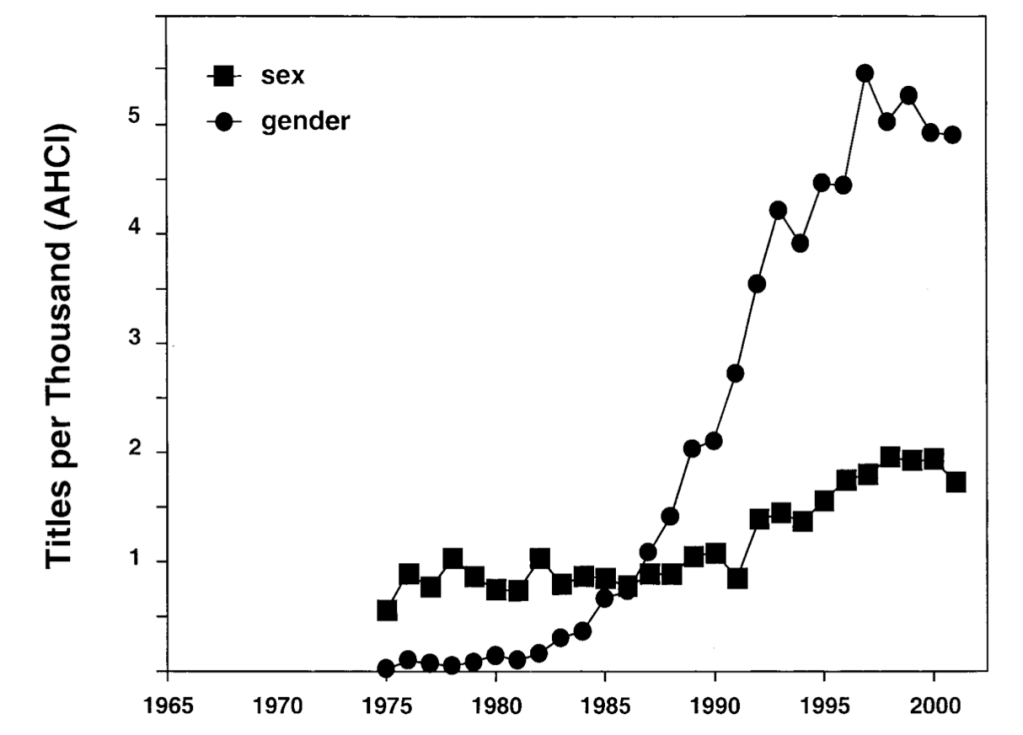

The blogger goes on cite an article by David Haig who, in a study published by Archives of Sexual Behavior in 2004, reviewed academic articles (over 30 million!) from the years 1945-2001 to determine the occurrences of the words “sex” and “gender.” Haig found that at the beginning of the period, the usages of the word “sex” were more frequent than usages of the word “gender.” This is because in the ebb and flow of synonyms, sex had become preferred. By the end of the period, however, uses of “gender” outnumbered uses of “sex,” especially in—wait for it—the arts, humanities, and social sciences.

Haig traces the shift to the introduction of the concept of “gender role” in 1955 by the notorious John Money. But it was not until feminists took up the term to distinguish the cultural and social aspects of differences between men and women from biological differences, he insists, that “gender” returned to prominence. Interestingly, he found that, “[s]ince then, the use of gender has tended to expand to encompass the biological, and a sex/gender distinction is now only fitfully observed.” As we all know, that would change with the ubiquitousness of queer theory and the appearance of gender affirming care.

In this first chart, tracking data drawn from the Science Citation Index (SCI), Haig found that, from the late 1970s, gender began a steady increase in frequency of use, partly at the expense of sex. He notes that this increase in frequency of the use prompted the FDA to adjust their guidelines in 1993 to require studies of “gender differences” in all new drug applications. Obviously, then, gender differences here would refer to genotypic and phenotypic differences between females and males; in the scientific literature, gender was understood as a synonym for sex and guidelines adjusted to include the word as used in this sense because of its growing popularity. This is an important fact to grasp, as the appearance of gender in the medical literature, when not a marketing term for gender affirming care, is often wrenched from context or assumed to mean “gender identity” all along (more on this concept in a moment).

The next two charts track data Haig gathered from the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) and the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AHCI). As you might expect, preference for the term gender rose rapidly, and it is in these disciplines that gender takes on its propagandistic meaning. This corresponds to the emergence of feminist, postmodernism, and queer politics that sought to differentiate the gender (or sex) roles that have existed in the gender binary since time immemorial (not just in human animals, but in animals across the kingdom), by reducing the roles to cultural and historical variability (which anthropologists an sociologists had never done), disconnecting them from reproductive anatomy and gamete size, and claiming that gender is purely a social construct and therefore arbitrary or mystified. It was from here that the medical-industrial complex, through the mechanisms of psychiatry and sexology, powerfully enabled by Robert Stoller’s invention of “gender identity,” picked up the ball and ran with it, substituting for scientific materialism and safeguarding vulnerable populations the pecuniary interests of the corporate state. (See Fear and Loathing in the Village of Chamounix: Monstrosity and the Deceits of Trans Joy.)

On the basis of this article, Gender World concludes that, “prior to 1955, the word ‘gender’ referred to grammatical categories used in some languages to form an agreement between a noun and other aspects of language, like adjectives, articles, pronouns, etc.” But this conclusion is plainly wrong (so is Haig’s assumption, dictated by his periodization) and, moreover, misses what Haig’s content analyses reveals.

First, as I have shown in this and other essays, the conclusion is false; gender was being used to refer to reproductive anatomy and gamete size centuries before Merriam-Webster revised the definition of gender. Even hints of this fact escape the blogger. “Old English made use of grammatical gender, but mostly stopped with Middle English,” he writes. “We still have a few references to gender in Modern English, such as pronouns (he and she), and nouns associated with some animals (man/woman, stallion/mare, ram/ewe, etc).” Why would there be distinctions among animals as “man/women,” “stallion/mare,” “ram/ewe,” etc.? I already showed why in an essay dedicated to this topic, Sex and Gender are Interchangeable Terms, where I explain that the names for males of different species vary (man, stallion, ram, dog, tom, hog, etc.). I also note that the pronoun for males are the same regardless of the species. They are “he/him.” If you refer to a hog as a “she,” the farmer will correct you.

Second, Haig’s content analyses reveal a project across the arts and sciences to sharply increase the frequency of the word “gender” to represent both a political-ideological and medical science term, initially expanding the word to include the social and cultural aspects identified by anthropologists and sociologists decades earlier in the concept of the “gender role” (still useful and valid concepts), while gaslighting the public by claiming that “gender” was originally a system of grammatical classifications ironically used to refer to the gender (today, strictly the sex) of animals and things (as kinds and types). In other words, only very recently was “gender” repurposed by queer theorists and medical corporations to manufacture an ideological construct and commercial term for political and marketing purposes. But I am repeating myself.

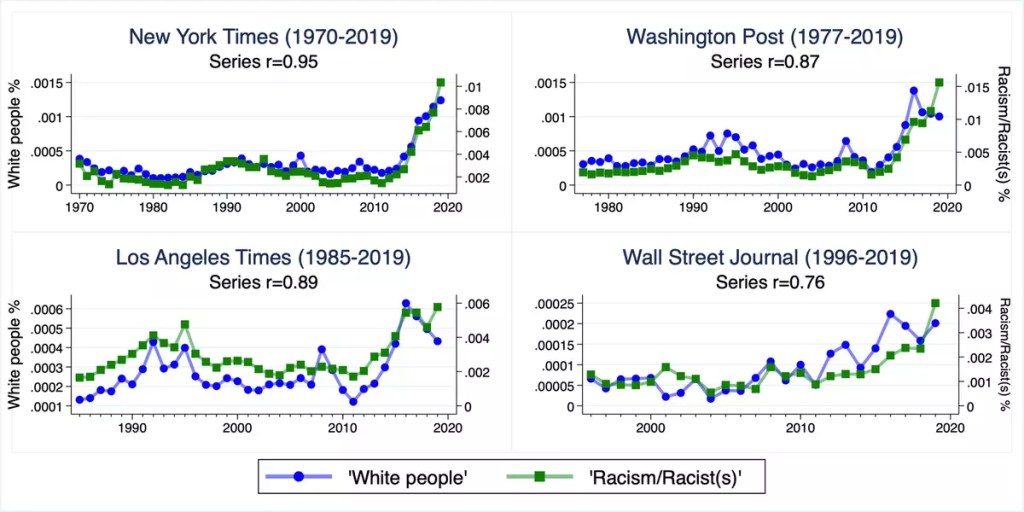

This is not the only time a project has materialized to rapidly alter mass perception by manufacturing words and meanings. In a detailed content analysis of major media sources published in Tablet in 2020, “How the Media Led the Great Racial Awakening,” Zach Goldberg tells us that, “[y]ears before Trump’s election the media dramatically increased coverage of racism and embraced new theories of racial consciousness that set the stage for the latest unrest.” Not just unrest. As I have shown, like queer theory, the jargon of critical race theory colonized the medical science space (see, e.g., my October 2020 essay The Problem of Critical Race Theory in Epidemiology: An Illustration.)

You can find Goldberg’s article here, and I strongly encourage you to read the whole thing, but I want to pull a few charts from the piece to make the point immediate for you. In the first two charts, the reader will see the drastic increase of reference to “racists” and “racism” occurring around 2010 and a corresponding rise in the percentage of the population who reported that racism in the United States is a problem—this after a long decline. If you ever needed to see the evidence of how the corporate media constructs and drives mass perception of social problems, Goldberg delivers it in spade (but then so did Haig).

Indicated by the next several charts, the use of terms like “racists” and “racism” were buttressed by a slew of novel or academic terms developed by progressive social scientists and historians and pushed out by the corporate media and culture industry: “systemic racism,” “structural racism,” and “institutional racism”; “racial privilege” and “white privilege”; “racial hierarchies,” “whiteness,” and “white supremacy”; “racial disparities,” “racial inequalities,” and “racial inequities.” In this way, the alleged effects of “whiteness,” “systemic racism,” etc., were identified as causing racial disparities and inequities without any demonstration of the validity of the alleged independent variables or their explanatory power. No matter, the terms comprised the assumption in force. Reinforced by race hustlers like Ibram X Kendi and Robin DiAngelo, and through constant repetition, the abstract facts of racial disparity became their own cause, especially since even suggesting they were explicable by reference to causes outside of the antiracist narrative risked being labeled a racist.

“But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought. A bad usage can spread by tradition and imitation even among people who should and do know better. ” —George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language” (1946)

I write in my essay Manipulating Reality by Manipulating Words: “By reducing definitions to power projection, to the manipulation of reality, proponents of [the postmodernist] view … mean to delegitimize the primary purpose of words, which is to describe and convey reality with accuracy, integrity, and precision (language’s evolutionary function), and repurpose words for exclusive use as tools for fabricating reality. When words cease to be regarded as a reliable means of describing and conveying truth, those who control the means of idea production can more readily rationalize their aims and desires by blurring the distinction between fiction and non-fiction.”

I continue, “Any of you who have more recently attended college and taken any humanities and social sciences courses, which is often required by the regime of ‘general education,’ will have learned that what is and its nature (the ontological) is determined by how we think about such things (the epistemological). It is very likely that you will have been told that the former is the result of the latter and, further, that we must not allow the masses to get their hairy little paws on the machinery of meaning production.” This is hegemonic across worlds of academic and corporate science: life in the woke progressive bubble is technocratic reflex. Ideology has replaced truth.