“Just as Darwin discovered the law of development of organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human history: the simple fact, hitherto concealed by an overgrowth of ideology, that mankind must first of all eat, drink, have shelter and clothing, before it can pursue politics, science, art, religion, etc.; that therefore the production of the immediate material means, and consequently the degree of economic development attained by a given people or during a given epoch, form the foundation upon which the state institutions, the legal conceptions, art, and even the ideas on religion, of the people concerned have been evolved, and in the light of which they must, therefore, be explained, instead of vice versa, as had hitherto been the case.” — Frederick Engels, Highgate Cemetery, London. March 17, 1883

A recent controversy has introduced me to a wider audience (see The Snitchy Dolls Return). Many of those who have just found me have noted that I identify as a Marxist, an identification wherein they see not an inconsiderable degree of irony given the nature of the controversy. Since many of them are on the political right, this identification may be off-putting; they found me in the context of a debate over my right to freely express my opinion about gender ideology, and thus may have initially thought of me as an ally.

I do not desire that any of them find this identification off-putting, so it seems to me useful to explain what I mean when I say that I identify as a Marxist. It’s not because I advocate for the socialist transformation of society (see my essays Marxist but not Socialist and Why I am not a Socialist). Indeed, I am a libertarian, a classical liberal who is critical of the political economy of corporate statism. It is rather because the work of Karl Marx, his materialist conception of history, is, or at least should be, the paradigm of the discipline to which I have devoted my professional life, namely sociology. To be sure, Marx was driven to his critique of capitalism in part because of his commitments to a socialist politics; at the same time, he believed these commitments required the development of science of history and of society.

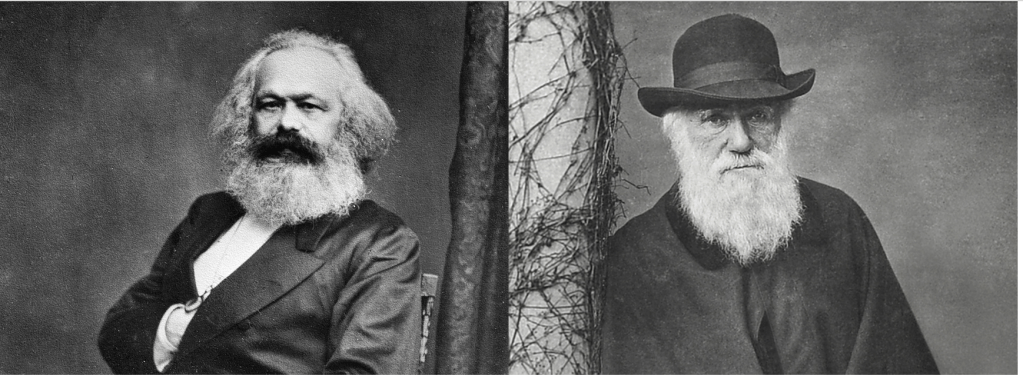

When I identify as a Marxist, I mean it in the same way as when I identify as a Darwinist. In the annals of intellectual history, Marx and Darwin left an indelible mark on their respective fields: Marx in social history; Darwin in natural history. While their names often evoke distinct realms of inquiry, a closer examination reveals a common project: to explain why things change over time—and why the take the forms they do.

To be sure, both Marx and Darwin are viewed with disdain by conservative observers, but Marx receives the most vitriol for his communist politics. Both were atheists, but the challenge Darwin poses to the Christian faith is moderated by the justification his naturalism provides for the competitive nature of capitalist relations (indeed, Darwin’s theory was inspired by Adam Smith’s invisible hand metaphor coined in The Wealth of Nations). However, putting politics aside (to the extent this is possible), it is worth considering Marx in the same way we consider Darwin, as having made a major contribution to our understanding of a domain of reality. Both were scientific materialists, which remains the superior way to understand the world around us.

At the heart of Marx’s analysis is his materialist conception of history, a framework that theorizes the interplay between economic forces, historical development, and social relations. Just as Darwin meticulously observed the natural world to unveil the mechanisms of evolution, Marx meticulously dissected the fabric of society to reveal the dynamics of class struggle and historical change. His seminal work, Capital, akin to Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, published less that a decade earlier, revolutionized our understanding of the social order by revealing the underlying laws governing capitalist production, the theory of surplus value, as Engels described it: “the special law of motion governing the present-day capitalist mode of production, and the bourgeois society that this mode of production has created. The discovery of surplus value suddenly threw light on the problem, in trying to solve which all previous investigations, of both bourgeois economists and socialist critics, had been groping in the dark.”

Much like Darwin’s natural history challenged prevailing notions of divine creation, of intelligent design, Marx’s critique of capitalism tore away the ideological veneer of bourgeois society, of which religion was a part, exposing its exploitative nature and inherent contradictions that make it both a powerhouse of material development and a source of perpetual crises. Just as Darwin demonstrated the interconnectedness of all living organisms through the principle of natural selection, Marx elucidated the ever changing arrangements of social classes and political power through the dialectic of revolutionary transformation. Both thinkers transcended the confines of their respective disciplines, offering comprehensive frameworks that continue to shape scholarly discourse and political debates to this day.

To identify as a Marxist, then, is to embrace a scientific approach to understanding the complexities of social phenomena, just as identifying as a Darwinist entails a commitment to the scientific exploration of the natural world. It is not an adherence to a set of dogmatic beliefs, but rather a recognition of the critical role of scientific materialism in elucidating the historical dynamics of human civilization. Just as Darwinism serves as a guiding principle in biological research, Marxism serves as a guiding principle in social analysis, providing invaluable insights into the historical processes and structural inequalities that shape our world. Both men faced vehement opposition from entrenched interests unwilling to relinquish their grip on power and privilege. Yet, their ideas have proved resilient, transcending ideological barriers and inspiring generations of scholars and activists to challenge the status quo and, in Marx’s case, strive for a more just society.

Marx saw Darwin’s theory as complementary to his own ideas about historical development, emphasizing the importance of material conditions and conflict in shaping human societies. Indeed, Darwin’s theory was the natural historical foundation for Marx’s base-superstructure model. Both Marx and Darwin approached their respective fields with a commitment to empirical evidence and a rejection of teleological explanations, seeking to uncover the underlying processes driving change and development—the laws of nature and of history. To embrace the legacies of both is to embrace a commitment to the relentless pursuit of knowledge in the service of understanding their respective domains.

Marx is often fingered as the cause of communist atrocities, but Marx did not lay out detailed plans for a communist society or advocate for the atrocities that marked man’s attempt to make such a society. Marx’s writings focused on analyzing the dynamics of capitalism and critiquing the social and economic structures that underpinned it. He envisioned communism as a society where class distinctions would be abolished, and the means of production would be collectively owned and managed by the workers, but he did not theorize such a condition, as such an order would need to first be established and defined through human labor. An opponent of utopia thinking, there is no blueprint for such a society in Marx’s work. (See Communism: The Real and the Theoretical, and Why Nomenclature Matters.)

It is therefore essential to distinguish between Marx’s ideas and the actions of individuals and regimes that claimed to be inspired by Marxism. While Marx’s theories provided the intellectual foundation for communist movements, including those governing societies that claimed to have at least reached the socialist stage of development, which were never communists by any definition Marx himself used, Marx himself did not advocate for the oppressive tactics or human rights abuses associated with those regimes. Critics often conflate Marx’s ideas with the actions of authoritarian regimes that claimed to be Marxist, such as the Soviet Union under Stalin and Maoist China. However, it’s crucial to recognize that these regime diverged significantly from Marx’s political goals and engaged in practices that Marx himself, a lover of liberty, would have condemned.

Had Marx the vision of future hindsight, he likely would have agreed with me about the socialist problematic. Famously, Marx is supposed to have said, “I am not a Marxist.” This was an expression of Marx’s frustration with the various interpretations and adaptations of his ideas by others, particularly some of his self-proclaimed followers. Marx lived during a time of intense intellectual and political ferment, and his ideas were often co-opted, distorted, or simplified by different political factions for their own purposes. Marx was critical of those who turned his ideas into dogma or rigid ideology, rather than engaging critically with the social context and material conditions of their own time. By disavowing the label, Marx signaled his reluctance to be associated with these simplistic or dogmatic interpretations of his work. So why do I identify as such? Again, for the same reason I identify as a Darwinist.