“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.”—LP Hartley (1953)

“My standpoint, from which the evolution of the economic formation of society is viewed as a process of natural history, can less than any other make the individual responsible for relations whose creature he socially remains, however much he may subjectively raise himself above them.”—Karl Marx (1867)

This settles the question of whether AP African American and Florida’s new standards say the same thing:

In Florida’s Public School Curriculum is Malinformation, I curated the words of Crystal Etienne, a seventh-grade civics teacher in Miami-Dade County, who said, “It’s disgusting to use children as pawns in their adult scheme.” She called the changes to Florida’s public school curriculum “indoctrination” in “white, Christian nationalism.” She said, “They feel like if you’re teaching the bad, it somehow takes away from the good and it doesn’t.” That is an interesting way of putting the matter, I noted in so many words. I also curated the words of Dwight Bullard, a former high school history teacher, who said that he couldn’t fathom telling his students that there’s a “silver lining in slavery.” He’s referring to the lesson plan that has enjoyed the most publicity, which reviews the wide range of habits and skills Africans acquired during slavery that they applied to their lives after Emancipation. “Imagine the blowback of the same teacher trying to give you the upside of Nazi Germany,” said Bullard, using the Hitler analogy. “Not only would it not be allowed, there would be bipartisan outrage over the idea that any teacher, a teacher or a curriculum trying to give the sunny side of Adolf Hitler. Yet we now have an African American history statute that is supposed to now give you this notion of the benevolent master, or the upside or benefit of being enslaved in America. It’s crazy.” As I noted in that essay, Bullard makes explicit, inverts, and leans into Etienne’s irony: if you’re teaching the good, this takes away from the bad.

Can one imagine a European history curriculum leaving out the initiation of the German Autobahn system during the Nazi regime? That would be like leaving out of an American history curriculum President Dwight D. Eisenhower initiating the Interstate Highway System (IHS). During Eisenhower’s presidency, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was involved in covert operations to overthrow foreign governments perceived as threats to US interests (the CIA orchestrated the overthrow of Iran’s democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953 and supported the coup that toppled the democratically elected President of Guatemala, Jacobo Arbenz, in 1954). These actions undermined the sovereignty of those nations and interfered in their internal affairs. This doesn’t make Eisenhower Hitler, of course. What about the development of the Volkswagen Beetle, initiated by the Nazi government, aimed at making cars accessible to ordinary German citizens? The idea was to create a “people’s car” (literally Volkswagen in German). After World War II, the production of the Beetle continued and became a popular, even iconic vehicle worldwide (I had several as a young man). The Nazi regime invested in rocket technology, which laid the groundwork for later developments in space exploration. Key figures like Wernher von Braun, who worked on Nazi rocket projects, played significant roles in the US space program after the war.

I am a bit of a rocketry nerd, so I want to spend a little time on von Braun work and associations in this area. Wernher von Braun was a German aerospace engineer and rocket scientist who was part of the team that developed the V-2 rocket for Nazi Germany. He was also a Nazi and an SS member. Towards the end of World War II, von Braun and some of his colleagues surrendered to the United States rather than fall into Soviet hands. In 1945, von Braun and his team were brought to the United States under a program known as “Operation Paperclip.” This program aimed to recruit German engineers, scientists, and technicians who had worked on rocketry and other advanced technologies for the Nazis. The goal was to utilize their expertise in the emerging Cold War competition, particularly in the context of the space race with the Soviet Union. In America, von Braun worked for the US Army Ordnance Corps and later joined the newly established National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). At NASA, he played a key role in developing the Saturn rockets, which were crucial for the Apollo program and eventually led to the successful moon landings. Von Braun is considered one of the fathers of rocketry and space exploration, but his association with the V-2 rocket and the Nazi regime has been a subject of controversy and debate throughout history. Should we dismiss his work because the Nazis financed it? Should we dismiss von Braun’s work because he was a Nazi?

Alexander the Great, the Macedonian king, a military conqueror who built an immense empire that stretched from Greece to India at the expense of an untold number of bodies, nonetheless spread of Hellenistic culture during his conquests, facilitating the appreciation of Greek art and ideas across the regions he conquered. This cultural diffusion, known as Hellenism, had a profound impact on the development of art, literature, and philosophy in the societies under his control and afterwards. He established Alexandria, a great city in Egypt that contributed mightily to the dissemination of knowledge and learning in the ancient world. His expeditions included scholars and scientists who documented the fauna and flora, climate and terrain, of the regions they traversed. This knowledge helped advance the understanding of the world during ancient times. Should this be left out of World history curricula because Alexander killed and maimed civilians as he conquered the known world? Shouldn’t we stop calling him “great”? Did the peoples he conquered not benefit from any of it?

Slavery was a common institution in the ancient world, and it played a significant role in the economies of various civilizations, including ancient Greece. As Alexander conquered and expanded the empire, he captured numerous prisoners of war from defeated territories, and many of these individuals were enslaved. These enslaved individuals were put to work as agricultural workers, construction laborers, and domestic servants. The use of slaves was prevalent in many ancient societies, and it was an integral part of the economy, providing a cheap labor source for various tasks. While Alexander is remembered for his military accomplishments and contributions to the spread of Hellenistic culture, the practice of slavery was a characteristic of his time, and it was not uncommon for conquerors and rulers of that era to take slaves from the peoples they subdued. What do we do with this historical fact?

Joseph Stalin, the ruthless Soviet dictator, responsible for countless atrocities, including purges and forced labor camps, nonetheless promoted rapid industrialization in the Soviet Union, which helped modernize the country and turn it into a major economic power. The Soviet Union rapidly developed heavy industries, such as steel, coal, and machinery production, turning it from an agrarian society into a major industrialized nation. This allowed the Soviet Union to prevail in World War II over Nazi Germany. When Stalin died, he could claim a legacy of taking a backward peripheral region of the world capitalist economy and powering it to the second-most technologically-advanced civilization in world history, raising millions out of ignorance and poverty, providing millions with education, housing, and medicine.

I have studied the history of the Soviet Union rather extensively (see my 2003 article The Soviet Union: State Capitalist or Siege Socialist? in Nature, Society, and Thought) and I am always amazed at how dismissive people are about that history because Stalin was responsible for a great many deaths. Under Stalin’s leadership, the Soviet government invested heavily in education and science, leading to substantial advancements in these areas. The literacy rate increased significantly, and access to education became more widespread, allowing for a better-educated population. This focus on education and research also facilitated important scientific breakthroughs, particularly in space exploration and technology. The totalitarian regime that overthrew the monarchy of a ruthless tsar trained up tens of thousands of engineers, physicians, scientists, and technicians. he government prioritized healthcare services, providing free medical care to all citizens. This led to improved life expectancy and a decline in infant mortality rates over the years. The Soviet emphasis on gender equality resulted in improvements for women’s rights. Women were granted equal rights to education and employment, leading to increased female participation in the workforce, particularly in traditionally male-dominated fields such as engineering and science. Does recognizing these facts make one an apologist for Stalin? Should we erase the proletarian workers who accomplished all this?

In a region where tribal feuds were common, Genghis Khan demonstrated exceptional diplomatic and military skills, forging alliances and earning the loyalty of the various clans. Through a keen understanding of political and social dynamics, Genghis Khan managed to unite the Mongol people, creating a strong and cohesive nation out of once-fractured tribes. Beyond military conquests, Genghis Khan’s rule had a lasting impact on the territories he conquered. Despite his fearsome reputation as a conqueror, he was also known for his religious tolerance and open-mindedness. He actively promoted cultural exchange and communication along the famous Silk Road, facilitating trade and the flow of ideas between the East and West. His policies ensured relative stability and security, allowing merchants, scholars, and travelers to move safely across the vast empire. Pax Mongolica encouraged the exchange of technologies, goods, and knowledge, leaving a lasting legacy on world history. Genghis Khan’s administrative accomplishments were equally significant. He implemented a legal code known as the Yassa, which served as a set of laws that governed various aspects of Mongol society, including governance, military organization, and social conduct. The Yassa helped maintain order within the vast and diverse territories of the empire and provided a framework for future Mongol rulers to govern effectively.

But what about that fearsome reputation as a conqueror? While Genghis Khan’s accomplishments as a military leader and empire builder are often praised, it is also true that his conquests resulted in the deaths of countless people. The expansion of the Mongol Empire was marked by brutal military campaigns, and his armies were known for their ruthlessness and ferocity in battle. During Genghis Khan’s conquests, entire cities were put to the sword. Cities that resisted the Mongol forces faced severe reprisals, leading to massive casualties. His military campaigns in Central Asia and the Middle East, particularly against the Khwarezmian Empire, resulted in widespread destruction and loss of life. Genghis Khan employed various tactics to strike fear into his enemies, such as killing large numbers of people to terrify and demoralize those who opposed him. These brutal actions were intended to deter resistance and ensure submission to Mongol rule. It is estimated that the Mongol conquests led by Genghis Khan and his successors resulted in the deaths of millions of people across Eurasia, making it one of the deadliest military campaigns in history. Indeed, Jack Weatherford, in Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World contends that the large-scale depopulation caused by the Mongol conquests resulted in the abandonment and reforestation of vast agricultural lands and, as a consequence, there was a significant increase in carbon sequestration, which led to a reduction in atmospheric carbon dioxide and a localized cooling effect in some regions.

While Genghis Khan is celebrated for his military achievements and his role in creating a vast empire, it is essential to acknowledge the darker aspects of his reign. The historical legacy of Genghis Khan remains complex, and his actions continue to be a subject of debate and examination among historians and scholars. Obvious, as a general rules, it is important to remember that acknowledging the achievements of men and movements does not justify the terrible conduct and human rights abuses that result—and Florida’s new curriculum is not at all reticent to require teachers to report on the conduct of oppressors and human rights abuses that occurred under slavery. History is a nuanced tapestry of both dark and light elements, and it’s essential to study and understand it critically. But the desire to deny any good in something is an ideological endeavor not an academic one.

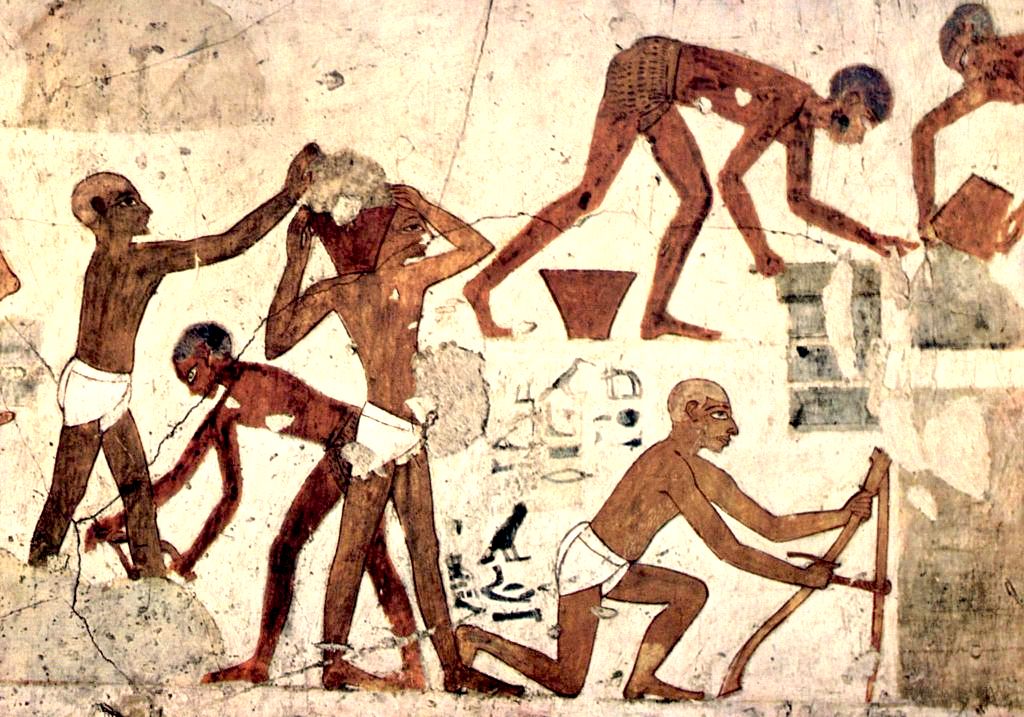

Slavery is one of the oldest modes of human exploitation. Its history dates back thousands of years, and it has been practiced in civilizations and regions around the world. This is crucial to understand in an era when opponents of the United States republic insinuate that the slave trade was uniquely European, chattel slavery uniquely American, slaves uniquely black and their oppressors uniquely white. The reality is that practice of slavery was widespread across different cultures, societies, and time periods. Slavery was commonly practiced in ancient civilizations, with slaves performing various tasks, including agricultural labor, domestic work, military service, and even skilled crafts. The historical evidence makes clear that the practice existed in ancient civilizations such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, and China. It was also present in pre-Columbian America, Africa, and various other regions. Slaves were obtained through conquest, debt, warfare, or being born into slavery due to their parents’ enslaved status (hereditary slavery). The transatlantic slave trade during the 15th to 19th centuries was a chapter in the history of slavery, where millions of Africans were forcibly transported to the Americas to work on plantations, but the trade in slaves and the system of chattel slavery in the US South is not unique in any of its aspects. That doesn’t make it wrong. It just means that the British colonies and later the US South were not novel.

When evaluating historical phenomena like slavery, it is essential to be objective, even if the practice is widely considered immoral by today’s standards—even if the practice is considered from the standpoint of universal and eternal human rights. The practice of slavery served as a major economic institution across space and time. In some historical contexts, slave labor provided the foundation for the economic prosperity of empires, states, and world-systems. Slavery allowed for the construction of monumental structures, the development of large agricultural estates, and the production of valuable goods and services. Obviously, the economic contributions of slavery should never be used as a justification for its moral acceptability, but the immorality of slavery does not negate the economic contributions of slavery. Slavery was associated with cultural diffusion, intellectual development, and technological transfer. Cultural practices, knowledge systems, and a universe of skills were transferred between peoples and societies. Agricultural innovations and techniques, architectural design, artistic and musical styles spread through the movement of enslaved individuals. Backwards peoples often experienced significant personal growth and development, knowledge and skills that allowed them to become successful in the societies in which they were enslaved. Moreover, enslaved individuals made significant cultural and intellectual contributions despite their constrained circumstances.

In addition to the double standard with respect to the United States during the antebellum period that the progressive demands, that is in how the oppressive situation of others in history are covered in public school curricula, teaching the good and the bad, the refusal to recognize the phenomenological and practical conditions experienced by individuals under slavery in the United States is odd in light of long-standing left-wing commitments and understandings—presuming for the sake of the point that the commitments of teachers are still left wing (they certainly say they are). Proletarian labor is exploited by capitalists and compelled to do so by a structurally coercive class situation. But no serious Marxist would fail to appreciate that there were and are among the proletariat those who applied skills learned on the job to their lives, such as finding a better job with higher wages and better working conditions, or organizing other workers with similar skills and trades to agitate for higher wages and better working conditions. Why is it well understood that the situation of the industrial workers, which also constitutes an exploitative relation, often characterized by low wages and poor working conditions, has a transformative effect on those who are compelled to work for a living? During the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the rise of factories led to a massive influx of rural workers into urban areas seeking employment. Over the course of development, these workers acquired valuable skills in operating machinery and factory processes. They learned to read and write. They developed a sense of solidarity and collective identity, leading to the growth of labor movements and trade unions, which advocated for workers’ rights and better working conditions.

And this development was not exclusive to the proletariat. Convict labor, or penal labor, involves the use of prisoners for various types of work, often as a form of punishment. It was prevalent during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, particularly in colonial and post-colonial settings, but it still exists today. In fact, the Thirteen Amendment, ratified in 1865, which forbade chattel slavery in the United States, allows for penal labor. Convict laborers faced severe and often brutal conditions. They were subjected to forced labor, sometimes on plantations or in mines, and experienced physical punishment and abuse by overseers or prison authorities. Despite the harsh treatment, many convict laborers acquired skills in various trades or agriculture. To be sure, these skills were sometimes undervalued and not appropriately recognized or utilized after their release, but they also afforded many convicts a way of living after confinement. Today, developing good habits and useful skills is an objective of rehabilitation and reentry into free society.

Indentured servitude involved individuals, often immigrants, signing a contract (indenture) to work for a specific employer or landowner for a set period in exchange for passage to a new country or some other benefit. Indentured servants faced challenging circumstances, including long and arduous labor contracts, limited freedoms, and often poor living conditions. The terms of their indenture could be abused or extended, leading to prolonged servitude. As in other systems of exploitation, indentured servants also acquired various skills based on their work assignments, which could include agriculture, domestic labor, or skilled crafts They also experienced cultural exchange, as many indentured servants came from diverse backgrounds and brought their traditions and practices to their new environments. These realities are often discussed in public school curriculum. Does this practice mean to deny the suffering of indentured servants? Or does it mean to convey the phenomenological and practical experiences of those who struggled through this period in their lives?

In all these cases, it’s important to recognize the exploitative nature of these labor systems, where the rights and freedoms of people were compromised. Nevertheless, individuals in these groups developed various skills and habits, some of which empowered them to resist exploitation and advocate for better conditions and rights. The struggles and contributions of these laboring groups have shaped labor movements and labor laws, influencing social and economic reforms over time. In the Florida curriculum, the list of skills and trades associated with slave labor is expansive. In addition to blacksmithing and carpentry and such, slaves were also cobblers, coopers, healers, hostlers, milliners, musicians, painter, sawyers, shoemakers, silversmiths, tailors, weavers, wheelwrights, and wigmakers. They worked in homes, on farms, on board ships, and in the shipbuilding industry. Children are not supposed to know about all this? My own family history in East Tennessee was enriched by the presence of blacks trained in blacksmithing and other skills and trades associated with mining. These skills allowed blacks to provide for their families after emancipation. The suggestion that blacks had no place in a free America and should return to Africa is understood as an unacceptable argument. How were freed slaves to live in the only country they had ever known?

Consider that Marx himself, in the 1967 Preface to Capital, Volume One, made sure to emphasize the point that exploitation and oppression changes the exploited and the oppressed, and that forecasting how things will develop over time requires understanding how the exploited and oppressed are changed. “Let us not deceive ourselves on this,” he writes. “As in the 18th century, the American war of independence sounded the tocsin for the European middle class, so that in the 19th century, the American Civil War sounded it for the European working class. In England the process of social disintegration is palpable. When it has reached a certain point, it must react on the Continent. There it will take a form more brutal or more humane, according to the degree of development of the working class itself. Apart from higher motives, therefore, their own most important interests dictate to the classes that are for the nonce the ruling ones, the removal of all legally removable hindrances to the free development of the working class. For this reason, as well as others, I have given so large a space in this volume to the history, the details, and the results of English factory legislation. One nation can and should learn from others. And even when a society has got upon the right track for the discovery of the natural laws of its movement—and it is the ultimate aim of this work, to lay bare the economic law of motion of modern society—it can neither clear by bold leaps, nor remove by legal enactments, the obstacles offered by the successive phases of its normal development. But it can shorten and lessen the birth-pangs.”

Moments later Marx writes, “The representatives of the English Crown in foreign countries there declare in so many words that in Germany, in France, to be brief, in all the civilized states of the European Continent, radical change in the existing relations between capital and labour is as evident and inevitable as in England. At the same time, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Mr. Wade, vice-president of the United States, declared in public meetings that, after the abolition of slavery, a radical change of the relations of capital and of property in land is next upon the order of the day. These are signs of the times, not to be hidden by purple mantles or black cassocks. They do not signify that tomorrow a miracle will happen. They show that, within the ruling classes themselves, a foreboding is dawning, that the present society is no solid crystal, but an organism capable of change, and is constantly changing.”

There is something else in all this, as well, and it goes to the method Marx employs, namely the dialectic. I am not a spiritual person (neither was Marx), but I know others are, and I wonder whether they have considered this piece, especially in light of the rhetoric of social justice and an appreciation of liberation theology in teaching programs and elsewhere in the colleges and universities, and that is the matter of Georg Hegel and his Phenomenology of Spirit, published in 1807, which explores the master-slave relation and finds in it a powerful development dynamic. This is considered one of the most complex and influential pieces of philosophical literature—and it bears directly on the question of life after emancipation. Hegel’s analysis of the master-slave dialectic is part of his broader exploration of human self-consciousness and the development of human freedom through history. The master-slave dialectic examines the fundamental dynamic between individuals engaged in a hierarchical relationship.

In specifying this relation, Hegel describes how two individuals interact with each other and how their identities and self-consciousness are shaped through this interaction. As a sociologist, I find his argument fascinating, but also morally compelling. The dynamic begins when one individual, the master, seeks recognition from the other, the slave. The master attempts to establish his self-worth and identity by asserting dominance and control over the slave, appropriating the creative work of the slave. The slave, on the other hand, becomes subservient and obeys the master’s commands to avoid punishment and death, alienated from his own creative powers. But the master-slave relation is asymmetrical and therefore unstable. While the master gains recognition from the slave, it is a hollow form of recognition because it is based on fear and forced subordination. The slave, on the other hand, finds that his own existence is contingent upon the master’s recognition of it, which denies him autonomy and true self-consciousness.

In Hegel’s view, consciousness and human freedom arise through the acknowledgment of and mutual recognition among individuals. The slave, in his labor and struggle for survival, and in the character of his milieu, develops skills and knowledge, which gives him a sense of mastery over his environment and situation. Through this process, he achieves self-consciousness and self-recognition and gains a level of independence. Hegel believed that human history is a process of continual development and self-realization, where individuals and societies move towards greater freedom and self-awareness through the recognition of each other’s humanity in the progress of working out and through history. To deny that the African grew from his experience as a slave is to deny him the fruit of his struggle for freedom—his emancipation, self-regard, and self-reliance. This is the path to equality, formal and substantive. I have often characterized woke progressives as neo-Hegelian, rejecting the claim by the woke and their conservative critics that progressives are neo-Marxists or in some way Marxist. However, that critique does not involve the insight Hegel had about the struggle for freedom and self-actualization and the raising up of the societal whole society in the process.

Progressives get neither Hegel’s insight nor his method. But the Old Left did. Martin Luther King, Jr. did. As a theologian, Hegel’s allegory could not have been lost on King. Hegel’s dialectical method, which involves the resolution of contradictions through a dynamic process that moves the situation to a greater unity of its parts and lifts it to a higher plane of development, had a profound impact on how modern theologians approached their questions. It encouraged a dynamic and evolving understanding of religious concepts, allowing for the reconciliation of seemingly opposing ideas—the interpenetration of opposites. Hegel’s concept of the “Absolute” or “Geist” (Spirit) as an evolving and self-realizing entity influenced theologians to explore new ways of understanding God’s nature and divine reality and how pragmatism might allow social movements to achieve justice on earth. All this led to discussions about immanence and transcendence in the divine and the relationship between God and the concrete world. Liberation theology and the ethic of social justice (not the identitarian brand) are children of this idea.

Are we not to consider how the black people today are the descendants of those forged by the dialectic, material and spiritual? Are we to think only about the way slavery has hampered the generations, a ghostly ball-and-chain the living drag behind them, to ask for reparations from those who never owned them—or owe them? Or might we have our children consider the character of spirit that resisted exploitation and oppression and took from the now deposed master his knowledge and history to raise themselves above their past? A White House official told NBC News that Kamala Harris was in Jacksonville to discuss ways to “protect fundamental freedoms, specifically, the freedom to learn and teach America’s full and true history.” Did she really mean this?

The presence of slavery in history has also spurred abolitionist movements, where people advocated for the end of slavery and the recognition of the rights and dignity of all individuals. This argument suggests that the presence of slavery in history (the phenomenon) had the purpose or function of spurring abolitionist movements and advocating for the recognition of rights and dignity of all individuals (the outcome). It implies that slavery existed to bring about the rise of abolitionist movements and promote the recognition of human rights. If I left it there, I would be assigning an intention or purpose to the historical phenomenon of slavery without addressing the complex cultural, economic, historical, political, and social factors that led to its existence. Obviously, slavery was not an institution designed to bring about abolitionist movements; rather, it was a deeply ingrained practice that emerged due to various historical circumstances, such as labor demands, economic interests, and deeply rooted societal norms.

What I mean to argue if I am to be rational about it is that the historical presence of slavery was met with significant resistance from abolitionist movements, which emerged in response to the grave injustices and human suffering caused by the institution. These movements advocated for the end of slavery and the recognition of the rights and dignity of all individuals, highlighting the importance of human rights and social justice. In other words, the struggle for freedom is consciousness raising, deepening understanding, and expanding recognition of species-being and commitment to human rights. Again, I hasten to emphasize that any potential positive aspects mentioned above should never negate or overshadow the profound dehumanization, injustice, and suffering endured by millions of enslaved individuals throughout history. Slavery, as an institution, was and is inherently oppressive and immoral. Modern ethical standards unequivocally condemn slavery as a violation of human rights and human dignity.

* * *

What lies behind the hyperbole over Florida’s new public school standards? Part of it is a desire to delegitimize Ron DeSantis, the progressive boogyman currently serving as Florida’s governor. But that’s an immediate thing. There is a long term strategy behind the “blacks-built-America” rhetoric. “American capitalism was built on the backs of slaves and the slave economy—and not just in the South. Some of these practices are still with us,” declares the website Though Huddle at Arizona State University. “Historian Calvin Schermerhorn explains how slavery built America without returning virtually any of the gains to the enslaved people—or their descendants. He also describes how racial inequality is part of our national DNA and why it persists.” Pharrell Williams writing in the pages of Time: “The activists who tossed chests of tea into the ocean to protest economic injustice were patriots. But they were also oppressors, unwilling to extend the freedoms for which they fought to everyone. America’s wealth was built on the slave labor of Black people: this is our past. To live up to America’s ideals, we must trust in a Black vision of the future.” He is wrong on every count.

This notion of a “national DNA” is a very tired metaphor, one that never really did have any authority behind it. The cliché aims to distract from the ethic and ideal of the American Creed: a set of guiding principles that are deeply ingrained in the American society and culture, principles including democracy, equality, individual liberty, justice, and the pursuit of happiness. These serve as a moral compass and are rightly expected to influence the behavior and actions of citizens, emphasizing a sense of responsibility, civic duty, and respect for one another. The American Creed is an aspirational vision of what Americans strive to be as a nation. It highlights the desire for a society that upholds the values of equality, freedom, and opportunity for all. The power of the Creed is evident in the abolition of slavery within the founding of the nation and the end of racial segregation a century after that.

What I am about to say is not to diminish the contributions made by Africans and their descendants, who have been a small minority of the US population, concentrated mostly in the South (over 90 percent of blacks lived in the south during slavery and for several decades afterwards), but the truth is that America was primarily built on the backs of European labor and their descendants—convicts, farmers, indentured servants, and proletarians. Primarily the English built this nation, but also the Dutch, the French, Germans, Irish, Italians, Norwegians, Polish, Scottish, Spanish, Swedish, and many other ethnic groups built this nation. And many non-Europeans built this nation, as well. The Chinese, Filipinos, Indians, Japanese, and Koreans built this nation. The American Indians built this nation. All of these groups suffered mightily in all of this—and all benefitted from the result, to be sure, by varying degrees, largely depending one assimilation. I know that is a triggering thing to say, but it seems necessary to say it in light of the constant rhetoric that America was built on the backs of black slaves. It wasn’t. Proletarian labor largely built America—black, brown, and white. Even during the time of slavery and before, the indentured servant and the convict were hard at work building America. (See Disney Says, “Slaves Built This Country.” Did They?)

The claim that America was built on the backs of black people is calculated (or at least functions) to do three things: (1) erase social class as the primary form of exploitation under capitalism (this is a capitalist society, and chattel slavery, alongside wage slavery, was a part of the capitalist system); (2) diminish the contributions made by Europeans and their descendants, who have always been the majority in America, to the building of this great nation, great because it mades flesh the Enlightenment spirit, which is a product of the European world system, and which the so-called “New American Revolution” seeks to destroy and replace with an authoritarian tribalist feudalistic system; (3) make it look like Europeans were all slave owners/drivers who sat around on their backsides all day commanding blacks to do everything. This is an utterly false narrative about America.

This is why you are hearing so much about Florida’s new standards. The curriculum doesn’t wash the feet of Black Lives Matter and woke progressives are furious about that. It interferes with the project to disorder America and maintain custodial control over black people established by paternalistic progressives. That slavery was common place for thousands of years before white people abolished it is history. Just don’t tell that to children. A man sold into slavery suffers no less because he is white. He may derive from his experience knowledge and skill that will advantage him after emancipation. This does not justify his enslavement. It only explains his situation.

The quote above “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there” is from the novel The Go-Between written by British author LP Hartley. It reflects the idea that looking back at historical periods can feel like observing a different culture or society because of the vast differences in attitudes, behaviors, and customs that may have prevailed in the past. We can still appreciate elements of other cultures while criticizing those elements that limit and oppress people. Islam is a profoundly patriarchal ideology. The mosque is a site of stunning mosaic work. Likewise, gospel music evolved as a form of expression and resistance for enslaved Africans, providing solace and hope amidst the hardships they faced. Blacks didn’t stop singing after Emancipation.