One of the arguments that those defending mass immigration are fond of making is that immigrants commit less crime than the native-born. I have written about this before (see Crime, Immigration, and the Economy; Obscuring the Crime-Immigration Connection). The argument has returned and offered as proof is a 2020 article published in PNAS, “Comparing crime rates between undocumented immigrants, legal immigrants, and native-born US citizens in Texas,” by Michael Light and associated (edited by Douglas Massey of American Apartheid fame).

The authors admit that “[t]he limited information we do have about undocumented criminality is not only conspicuously scant but also highly inconsistent.” The authors cite two studies: “A 2018 report from the Cato Institute found that arrest and conviction rates for undocumented immigrants are lower than those of native-born individuals. Research by the Crime Prevention Research Center in that same year, however, reached the exact opposite conclusion.” They comment: “Neither of these studies was peer-reviewed, and thus, their data and methodologies have not been subject to scientific scrutiny.” Why the need for peer review is unclear. Peer review is a historically recent device for establishing pseudo-legitimacy. Perhaps it is to obscure the fact that the second study, “Undocumented Immigrants, U.S. Citizens, and Convicted Criminals in Arizona,” was conducted by John Lott, a very serious scholar whose work I recently summarized in Corporate Media and Democrats Distorting Crime in America. Peer review does nothing to enhance the validity and soundness of Lott’s work.

I will argue in this essay that the point of Light and associate’s exercise is irrelevant to the question that prompts it, namely public concern about illegal immigration and crime. I will argue further that a conclusion they reach is rather obviously wrong. The conclusion: “Our findings help us understand why the most aggressive immigrant removal programs have not delivered on their crime reduction promises and are unlikely to do so in the future.” To deal with this claim forthwith, if, say, ten million illegal aliens were removed from the United States, this would result in a significant reduction of crime. How could it not? As for the point of the study, I will address this by asking the reader to engage with me in a thought experiment: the introduction of a thousand immigrants into a small community with a population of a thousand people. Some might find this example unrealistic, but by way of real-world experience, only last year 400 immigrants were relocated in the small village of Upahl, Germany. Upahl’s native-born population is only 500.

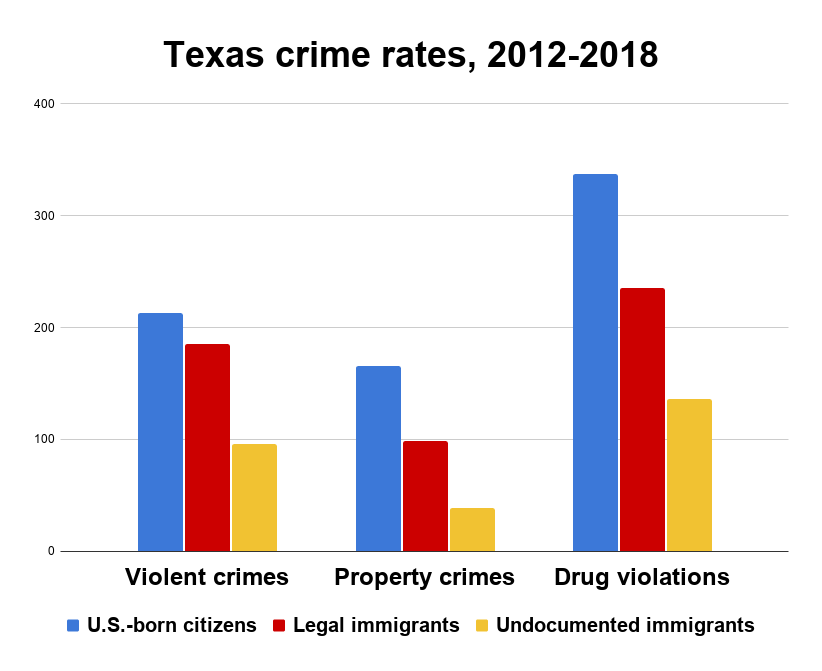

For this demonstration, let’s use arrest rates, since this is what Light and associated use. This is useful for Light’s purposes because, with arrest, the authorities can determine immigration status. If crimes reported to the police were used, then immigration status will remain unknown for a significant proportion of crimes reported. An immigrant in the country illegally has already committed a crime, but let’s put that aside and agree that the crime in question is an Index crime—aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, motor vehicle theft, murder, rape, and robbery. Light and associates include felony drug crimes. Doing so, Light and associates find that, for the period 2012-2018, “[t]he gaps between native-born citizens and undocumented immigrants are substantial: US-born citizens are over 2 times more likely to be arrested for violent crimes, 2.5 times more likely to be arrested for drug crimes, and over 4 times more likely to be arrested for property crimes.”

So let’s consider our small community of a thousand citizens. Fifty of them have each committed a crime in which there is an arrest. That’s fifty arrests. The arrest rate among citizens is 5 percent, which is rather substantial. Citizens in this community are already heavily burdened by crime and other social ills. Now suppose a thousand immigrants move into the community and twenty-five of them each have committed a crime leading to an arrest. The arrest rate is 2.5 percent. In other words, the rate of arrests among immigrants for crime commission relative to citizens is half as much, albeit still significant. With the introduction of the immigrants, the incidence of crime in the community as measured by arrests has increased by 50 percent—whatever the relative rates for the different groups. That is a substantial rise in the number of arrests for serious crime.

We might reasonably expect that citizens will be among the victims of immigrant crimes, so whatever the relative rates for the two groups, the presence of immigrants has increased the risk of victimization for citizens. (You might wish for me to note that immigrants may be the victims of native-born perpetrators. If the immigrants weren’t there, then they wouldn’t face this possibility.) In addition to greater susceptibility to criminal victimization, citizens also experience greater competition for jobs and resources (housing, for example). The taxpayers of the community also shoulder a greater burden, as the immigrants use public infrastructure, public services, etc. As noted, the community is already burdened by a range of social problems. The presence of the immigrants compounds these problems.

The relevant question to ask about the quality of like for the citizens is a rather straightforward one: How is the lower arrest rate for immigrants relevant to the experiences of the native-born? How does it matter to imperiled citizen in the real world they have to navigate that immigrants are less likely to be arrested for crime? Why should the citizens of the community endure even more crime and additional and exacerbated burdens? Those defending immigrant crime aren’t suggesting the government kick citizens out of the country, are they? (I have actually heard this said.) Citizens have a right to be in their own country whatever the degree of criminality. However, the government can deport immigrants or keep them out of my country in the first place, thus effectively reducing the arrest rate. After all, immigrants aren’t supposed to be in the community—or even in the country.

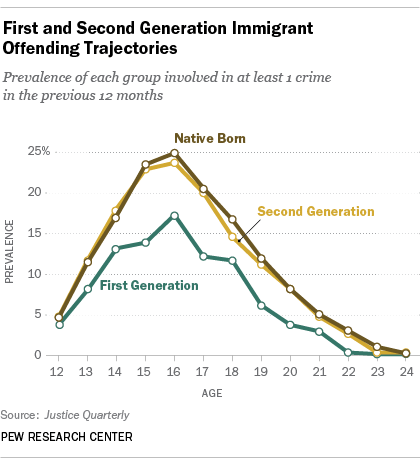

Moreover, immigrants have children, and whatever one might say about the relative prevalence of offending between native born and first generation immigrants, by the second generation, the prevalence is the same as native born. The above graph depicts the age crime curve. Note when crime peaks. We know that the age crime curve is generated from criminal behavior by males, as males are drastically overrepresented in serious crime. This means that the more males in the population, the greater the prevalence of criminal offending. Who the illegal immigrants are is therefore important to consider. If most of them are young males, then this will have a greater impact on public safety than if they were families or young women. I believe readers have a pretty good understanding of who have been illegally crossing the southern border.

The relative arrest rates may be some interest if one is trying to understand crime causation. But to do this we first need to have accurate statistics, and arrest rates aren’t going to tell us how much crime there is but only how many people were arrested. Moreover, immigrants could be committing more crime than citizens even if more citizens are arrested for crime. I have good reason to suspect that immigrants are underrepresented in crime statistics. If true, our imagined community is in an even worst situation.

Those of us who study crime are frustrated by reporting bias. Not all victims report crime to the police. We know that the number of crimes reported to the police is less than half of the number crimes victims will report in scientific victimization surveys. Not only are not all crimes reported to the police, not all crimes lead to an arrest, not all reported crimes are recorded by police, and not all recorded crimes are reported to the federal government who publishes these data. Crimes committed by immigrants may be underreported because victims are also immigrants and fear interacting with authorities who may determine their immigration status and deport them. This will lead to fewer arrests of immigrants who commit crime. New arrivals are unknown to police and are not among the usual suspects. As a result, they are therefore harder to identify and find. And with the population increase, there are fewer cops per capita to deter crime.

That there are persons unknown to police and that police are struggling to control crime in their community is of relevance to the citizens who must endure more crime in their community. The average citizen is not interested in conducting a study of crime causation. He is interested in safe streets, and he knows crime has increased with the increased presence of illegal immigrants in his community. In other words, the relative rates of offending between different citizens and immigrants is only relevant because the statistics confirm that increase in crime is due to the increase in immigrants. It was bad enough as it was. He doesn’t want to see it get worse. So he will rationally and rightly oppose the increase of immigrants in his community. And if his government does not reflect his interests, as it should, then his government has failed him.