Yesterday, the text of the bill made public on Sunday evening, the House voted on a deal negotiated by the White House and House Republicans that would suspend the nation’s borrowing cap until January 2025, enabling the debt to grow beyond the ceiling. The bill imposes a cap on non-defense discretionary spending, which covers areas such as public education and transportation, for fiscal year 2024, removing the debt limit as a potential issue in the 2024 presidential election (evidence of establishment influence on Republican Party leadership). The deal allows for a one percent increase in 2025. After fiscal year 2025, there would be no budget caps.

Leaders of both parties in Congress persuaded enough of their members to support the agreement, which contains provisions that are not favored by lawmakers on either side. Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy faced a potential revolt by populists in his party, those who held out during McCarthy’s ascension to the Speaker’s chair to successfully extract concessions from the front runner (for example, hearings on the weaponization of government, which have so far produced bombshell revelations concerning collusion between business firms and deep state operatives). Some Democrats had their own objections. “My red line has already been surpassed,” New York’s Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez warned. “I mean, where do we start?” Then she ticked off items in a list that included work requirements and cuts to programs. “I would never—I would never—vote for that.” And she didn’t.

In the end, 165 Democrats voted for the bill, along with 164 Republicans, and the House adopted the measure on a 314-117 vote. Now the bill moves to the Senate, where majority leader Chuck Schumer has promised to put it to a quick vote. The Senate, the seat of the legislative establishment, is almost certain to pass the measure. They have to get it to the president’s desk by June 5, an arbitrary deadline set by UC-Berkeley professor emeritus Janet Yellen, current Secretary of the Treasury and former chair of the Federal Reserve. Yellen is a long-standing Democratic Party insider.

According to a fact sheet distributed by the House GOP, non-defense discretionary spending would be rolled back to fiscal year 2022 levels, with federal spending limited to one percent annual growth for the next six years (in the bill passed by the House the limit on annual growth in spending extended to a decade, with defense spending again excluded). The breakdown of non-defense discretionary spending for fiscal year 2024 would be approximately $704 billion. Out of this amount, $121 billion would be allocated for veterans’ medical care, and $583 billion for other areas. According to the bill’s text, $886 billion would be allocated to defense spending. In other words, retirement benefits excluded, more than a trillion dollars will be spent on the military and its liabilities annually.

The bill temporarily expanding work requirements for certain adults receiving food stamps. Currently, childless, able-bodied adults aged 18 to 49 can only receive food stamps for three months within a three-year period unless they work at least 20 hours a week or meet other criteria. The agreement would gradually raise the upper age limit for this mandate to 55. The deal would also increase exemptions for veterans, homeless individuals, and former foster youth in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), commonly known as food stamps. All these changes would be in effect until 2030. The agreement also seeks to tighten the existing work requirements in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, primarily by adjusting the work participation rate credits that states can receive for reducing their caseloads. Work requirements would not be introduced in Medicaid, a provision which House Republicans had previously called for in their debt ceiling bill.

There is a lot in this bill to which I object. That the military budget isn’t reduced is troubling in light of the facts that tens of billions continue to flow to Ukraine to fight a proxy war with Russia and very little is being done to deter an increasingly aggressive mainland China or to stop the invasion of the United States at its southern border. I disagree with the expanding work requirements unless there is also provisions for closing the southern border and deporting the millions of illegal aliens who have entered the country, punishing corporations who offshore production, and funding for jobs and job training for those required to work under the requirements. More broadly, I oppose the panic over the debt limit that puts the nation under duress to support an agreement that won’t solve the problems the working class of America faces but will in fact continue the process of turning future generations into debt-encumbered serfs and be used to justify dismantling the social safety net so many Americans depend on for survival.

One of my areas of specialization is political economy, in particular international political economy and world systems theory. In my graduate studies in sociology, I focused on the dynamics and history of the capitalist mode of production, theories of development and underdevelopment, and the causes of capitalist crisis. Because my appointment at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay is based on my other specialization, namely law and order, I am not really known in my field as a political economist. However, political economy is the beating heart of Marxist sociology, which is my approach in most matters sociological, and I continue to keep abreast of the literature, as well as emerging economic trends.

In this blog, I want to bring my training to bear on the current macroeconomic economic situation. However, I want to emphasize at the outset that the present blog is less about the specific moment than it is about sketching the history of economic thought as it bears on the economic history of the United States and the world capitalist economy for the purposes of developing a model to allows for a clearer understanding of the present moment, as well as strategies for addressing problems associated with it. This blog will provide readers with nomenclature and key schools of thought and theories they might find useful in explaining the world around them and understanding how macroeconomics impacts them and their families and communities. My hope is that will at least be helpful in navigating arguments and information distributed in media, podcasts, and the various salons of the twenty-first century, both physical to virtual spaces. I also want to stress that I do not develop such a model here. The primary purpose of this educational is educational.

* * *

Macroeconomics is a branch of economics that focuses on the study of the overall behavior and performance of an economy. It deals with the analysis of such variables as economic growth, government action, and labor market dynamics. Macroeconomics examines the interactions between different sectors and agents within an economy, including business, government, and households, as well as the dynamics of international markets, including capital and labor markets. In sum, macroeconomics aims to understand and explain the factors that influence economic outcomes on a grand scale, which in the current period means the global scale. (You got a taste of this in my recent blog Maoism and Wokism and the Tyranny of Bureaucratic Collectivism, where I focused on the development of China and its emergence as a dominant economic force in the global economy.)

Key topics in macroeconomics include economic growth (productive capacity, living standards), business cycles (expansion and contraction), labor markets (human capital, wages), fiscal policy (taxing and spending), monetary policy (central banks, money supply, interest rates), international trade and finance (balance of payments, exchange rates, trade flows), inflation, which effects price level and purchasing power, and globalization (commodity chains, supply chains). Globalization refers to the interconnectedness and interdependence of economies across borders and the effect interconnectedness and interdependence of economies has on national sovereignty and cultural integrity. I will touch on many of these topics in this blog.

Macroeconomists use various theoretical models and empirical methods to understand and predict the behavior of these economic variables. As noted in the previous section, I work from a Marxist standpoint, what Karl Marx called the “materialist conception of history,” or historical materialism. Because the insights and research in macroeconomic analysis generally hail from standpoints that (at least formally) exclude Marxist assumptions, which are anathema to both bourgeois and progressive economics, the theories that inform the choices and decisions business firms and policymakers make regarding strategies for addressing economic challenges and achieving desirable outcomes are often substantially ideological. Considering this, I thought it would be useful to review basic macroeconomics in a way that included the standpoint of historical materialism.

To give the discussion a concrete point of departure, I begin with the panic of the moment: the national debt of the United States and the risk of default. As of May 1, 2023, the national debt has reached 31.46 trillion dollars. The debt is accumulated through deficits, which occur when government spending exceeds revenues; for every year the federal government runs a deficit, the national debt grows because of the growing amount of money borrowed. My apologies if the reader understand the difference between debt and deficit, but in my experience few people do, I want to proceed considering that not all my readers have a sufficient understanding for the terms of the discussion.

For decades, the federal government has been unable to fund basic programs and public services without borrowing money. The federal governments spent 28.7 percent more than it received in revenue in fiscal year 2022, resulting in a 1.45 trillion-dollar deficit, a number that is difficult to wrap one’s mind around given that it seems not long ago at all that this number reflect the national debt. At this pace, the national debt will increase 14.5 trillion dollars over the next decade. This is according to the Department of the Treasury. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), deficits 2024-2033 will total more than twenty trillion dollars.

The panic is that the government will default on its debt unless it raises the debt ceiling, a move that allows more government borrowing. However, this does not solve the problem of the mounting financial burden placed on the backs of future generations—indeed, it worsens the problem. A 2022 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report warns that the burgeoning national debt is unsustainable not only in the long term but in the intermediate term. According to 2022 budget outlook, the CBO projects that, based on economic forecasts, debt as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) will outpace GDP over the next thirty years, exceeding 180 percent of GDP by 2050 (see the above chart).

In the context of government debt, default occurs when a government is unable or unwilling to meet its obligations to repay the interest or principal on its debt. When a government defaults on its debt, it fails to make the required payments to its creditors, such as bondholders or international financial institutions (depending on the position of the country to regional and global economic systems). As I understand it, the United States government has enough cash on hand to pay its creditors. Moreover, it can rescind tens if not hundreds of billions of appropriated funds that have not been spent (more than the unspent and uncommitted pandemic relief money identified in the bill). Talk of default by Democrats and the corporate media is deception by nomenclature. Default is not the same thing as not being able to pay the bills. That’s why elites are fighting over the debt limit. Democrats want to raise the debt ceiling to borrow more money to pay for social programs. Republicans are fighting to keep spending from growing.

My Republican senator here in Wisconsin, Ron Johnson, asserts that the federal government possesses abundant funds to fulfill its financial obligations. He contends that President Joe Biden and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen need to exercise control over their spending practices. “We have more than enough revenue” to address the national debt, cover interest payments, fund Social Security, and finance Medicare, he recently argued, indicating that he will likely vote against the debt ceiling bill. Drawing upon his accounting background, his assessment is that the government is overspending and should establish a baseline informed by factors such as population, growth, and inflation. The current debt ceiling deal doesn’t involve an increase but rather a suspension of the ceiling, he notes, a fact he decries as dishonest, advocating instead for a clear dollar amount increase that would inform the American public of the additional spending being proposed.

Of course, default is a looming possibility given the extent of mismanagement and bad theory all around. Default may occur for various reasons, including economic crises, fiscal mismanagement, political instability, and unsustainable debt levels. Today’s crisis features all four. I’m preparing a future blog on the problem of legitimation crisis to discuss the political sociological side of this, but it will suffice to say here that the United States is entering a full spectrum crisis—economic, political, and cultural (some even say spiritual). The current situation carries the potential for severe consequences for both the government and the economy, leading to currency depreciation, higher borrowing costs, loss of investor confidence, reduced access to international financial markets, and further economic instability. If you reason dialectically, you understand that effects deepen the causes.

(I will avoid notes in this blog, but I think this one is necessary. As implied a paragraph ago, in some cases, governments seek assistance from international organizations, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), to address their debt issues and restructure their obligations to avoid default. This would be an embarrassment to the world’s largest economy. It would shake the faith not only in the global capitalist economy, but in international relations and geopolitics. The United States embodies the paradox of “too big to fail.”)

The government not paying its bills, often referred to as a government shutdown or a fiscal crisis, typically occurs when the government is unable to pass a budget or appropriate funds to finance ongoing operations. This situation arises when there is a political impasse, a failure to reach a consensus on budgetary matters, or other governance challenges. That’s all part of the deliberative democratic process. Spending projects and priorities lie at the heart of real politics. To be sure, the government may not have sufficient funds to meet its day-to-day expenses, such as paying salaries to government employees, funding public services, or fulfilling contractual obligations, but that’s the problem of administrative state and the technocratic apparatus. Editorializing for a moment (it won’t be the last time), citizens should never be slaves to interests of the permanent political class and its functionaries.

Accuracy and honesty require that we emphasize that, while both default on government debt and the government not paying its bills can have significant economic and financial implications, they are distinct phenomena. Default relates specifically to the government’s inability to honor its debt obligations, while the government not paying its bills refers to a broader situation of fiscal strain that affects the government’s ability to meet its various financial commitments. As noted a moment ago, this nation can honor its debt obligations. As for paying its bills, when you and I face this same thing at home or at our business, we either find a way to cut spending or increase our income (revenue). A lot of state governments must do this, as well. We may have to make hard choices. We may have to change the way we do things.

Before getting to what we need to do, at least an assessment of the viability of arguments and theories about policies, I want to acknowledge that the government can borrow money to cover its expenses, including paying its bills, and briefly explain how this is done. Governments often engage in borrowing by issuing debt instruments such as treasury bonds, bills, or notes to raise funds from investors and financial institutions. This borrowing allows the government to finance its operations, invest in infrastructure (if it is wise), fund public programs (if it is prudent), and meet its financial obligations (which it must do to maintain its legitimacy). When the government borrows to pay its bills, it essentially uses the borrowed funds to cover immediate expenses.

The problem of debt can become more troublesome during periods when tax revenues or other sources of income are insufficient to meet the government’s spending commitments. However, even with greater than average revenue generation, the government spending considerably more than it takes in remains the core problem. The relation occurs in a complex set of other relations. According to the Tax Foundation, in 2023, revenues will equal 18.3 percent of GDP, compared to a 50-year average of 17.4 percent, while spending will equal 23.7 percent of GDP, compared to a 50-year average of 20.1 percent. The means that the project interests costs will grow from 2.4 percent of GDP in 2023 to 3.6 percent of GDP over the next decade. Debt held by the public will reach its highest level ever recorded by 2033 at 118 percent.

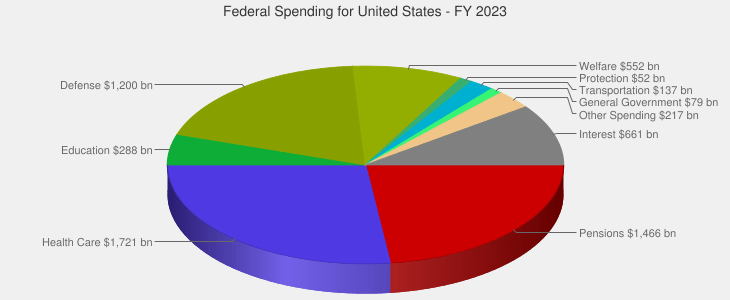

When a government takes on more debt, it leads to an increase in interest payments, which become a greater portion of the government’s budget over time. The interest payments on government debt represent the cost of borrowing and servicing the debt; as the government accumulates more debt, the total amount of outstanding debt increases, and with it, the interest obligations. If the government’s debt burden grows faster than its ability to generate sufficient revenue or control spending, a larger portion of the budget will need to be allocated to servicing the interest payments. The chart below is reflects the unified budget. Even including the trust funds, at 661 billion dollars in 2023, the annual interest paid on the debt comprises a large portion of the budget.

When interest payments become a large portion of the government’s budget, it can have several implications immediate and potential. It reduces the amount of funds available for other government expenditures, such as public services, infrastructure investments, or social programs. It may lead to difficult choices and potential cuts in other areas of the budget. If a significant portion of the budget is dedicated to servicing debt, it can create fiscal imbalances and limit the government’s ability to respond to economic shocks or invest in priority areas. It can also lead to higher borrowing costs in the future, as lenders may perceive increased risk associated with the government’s debt sustainability.

When a government increases its borrowing and accumulates more debt, it puts upward pressure on interest rates in the economy. The increased borrowing by the government leads to higher demand for loanable funds in the financial markets. If the supply of savings or available funds for lending remains relatively constant, the increased demand for borrowing can push interest rates higher due to the increased competition for those funds. This has a “crowding out” effect, as government borrowing competes with private sector borrowers for the available pool of funds. Additionally, a larger government debt burden raises concerns among investors and lenders about the government’s ability to repay its obligations. If lenders perceive higher risk associated with lending to the government, they may demand higher interest rates as compensation for the increased risk.

There are many other factors to consider: monetary policy, inflation (real and anticipated), central bank action, and the overall economic environment. The economic environment is especially crucial albeit often feeling like an abstraction. In times of downturns or when central banks implement accommodative monetary policies, interest rates may remain low despite increased government borrowing; however, excessive government borrowing and unsustainable debt levels eventually lead to higher borrowing costs and increased interest rates if investors and lenders lose confidence in the government’s ability to manage its debt. This how governments can suddenly find themselves in crises for which they are ill-prepared.

An unsustainable level of government debt potentially negatively affects economic growth and usually does. To stress some things already said and introduce others to make some crucial connections, when the government borrows extensively, it increases the demand for loanable funds and can crowd out private borrowers, such as businesses and households. Reduced access to credit for the private sector hinders investment, productivity, and overall economic growth. Higher interest rates increase borrowing costs for businesses and individuals, making it more expensive to invest, expand business, or purchase goods and services. This dampens economic activity and slows down growth. High levels of government debt lead to expectations of future tax increases to service the debt. Anticipated future tax burdens discourage consumption, entrepreneurship, and private sector investment. Excessive government debt can limit a government’s ability to respond effectively to economic crisis. When debt levels are already high, governments has less room to implement expansionary fiscal policies, such as increased government spending or tax cuts, which are often used to stimulate economic growth during recessions.

For readers wondering if all government debt is necessarily detrimental to economic growth, the answer is no, absolutely not. Moderate levels of debt used to finance productive investments, such as education or infrastructure projects, can contribute to long-term economic growth by enhancing productivity, improving the scope and depth of skills of the labor supply, and promoting innovation. A country can invest in itself the same way a business firm can invest in itself. At the same time systemic consequences and unintended effects can emerge.

Rising organic composition of capital (OCC) associated with rising productivity has in the past resulted in higher wages in capital-intensive sectors, and government spending has contributed to these productivity gains. However, rising OCC also comes at the expense of a smaller work force, as greater productivity mean fewer workers can do more work, while globalization, both offshoring and immigration, driven by the same imperative to accumulate capital, puts downward pressure on the aggregate income of low-wage labor-intensive sectors. This has led to growing redundancy in labor markets and a fall in the rate of profit. Slower economic growth is a result of the capacity to produce large amounts of surplus value without the corresponding purchasing power to realize that surplus as profit in the market. In other words, in the present moment, the rationalization of production is the root cause of looming crisis of capitalism. This complex fact should frame discussions concerning the problems covered in this blog.

“By composition of capital we mean the proportion of its active and passive components, i.e., of variable and constant capital,” Marx writes Capital Volume III, Chapter 8. By “variable capital” Marx means the proportion of capital invested in wages, i.e., the purchase of labor-power. The capital is “variable” because it may produce surplus value in the labor process over and above the “necessary labor time.” By “constant capital” (“fixed capital” in bourgeois economics) Marx refers to “a definite quantity of means of production,” the proportion of capital invested in the objects of product that are embodied in the commodity, as well as machinery, materials, tools, etc. used up in production, which must be renewed. In this process there is a tendency of the OCC to rise over time. I discuss the consequences in this blog: The End of Work and Value (see also my blog Marxian Nationalism and the Globalist Threat).

In capitalist economies, surplus value is generated through the exploitation of labor. Workers produce more value through their labor than the value they receive in the form of wages. Capitalists realize this surplus value as profit by selling the goods and services produced in the market. Marxists classify a crisis in which capitalists struggle to realize surplus value as profit in the market as a realization crisis. In a realization crisis, the issue lies not in the production of surplus value itself but rather in the realization or actualization of that value as profit in the market. Factors such as declining demand, insufficient consumer purchasing power, or market saturation can hinder the sale and realization of surplus value, leading to a “crisis in profitability for capitalist enterprises. For mainstream economics, this is commonly referred to as a “profitability crisis.” This brings us to the economics of the business cycle, i.e., the explanation of business expansions and contractions.

Along with talk about default coming from the progressive side, we hear a lot about the problem of governments printing money, with conservatives citing extreme cases such as Venezuela and Argentina. Printing money, i.e., monetary expansion, is different from taking on more debt. Printing money refers to the process by which a central bank increases the money supply in an economy. This is typically done by the central bank purchasing financial assets, such as government bonds or other securities, from banks or the private sector. The central bank creates new money to pay for these assets, effectively injecting money into the economy. The goal of monetary expansion is to stimulate economic activity, boost lending and investment, and combat deflationary pressures. By increasing the money supply, central banks aim to lower interest rates, encourage borrowing and spending, and promote economic growth.

But as is so often the case, there is the other side of the thing. Excessive or uncontrolled money creation prompts inflationary pressures and erodes the value of a currency. The role of central banks is to implement monetary policy to carefully manage money supply growth, aiming to strike a balance between promoting economic activity and maintaining price stability. But this is presuming that central banks are apolitical generally and not subject to political agenda in the here and there, a naive presumption. (Venezuela continues to illustrate why printing money is not the optimal strategy for dealing with economic problems.)

* * *

What is to be done? One thing that needs to happen is that the government needs to raise revenues. This cannot be accomplished solely with tax increases. Indeed, tax increases come with problems—one of which is the problem of revenue reduction in the long term: excessive taxation puts a drag on economic growth necessary for raising revenues. There is a pair of paradoxes to consider here. The first is the paradox of reducing revenues by sabotaging economic growth with higher taxes. The second is the paradox of raising revenues by stimulating economic growth with lower taxes. Some readers will want to remind me of the nearly confiscatory rates of taxation on the top income groups in United States during the “Golden Age of Capitalism.” I am sympathetic to this position. However, it is important to consider the broader economic and historical context.

The post-war era witnessed significant economic expansion characterized by robust growth and rising living standards. Other factors, such as increased government spending, technological advancements, and world economic conditions played crucial roles in fostering economic growth. Things that work in some contexts, don’t work in others. The application of theory induced from one set of facts to a situation with a very different set of facts is an ideological or religious move, not a scientific one. That said, observers have differing views on the specific impact of high tax rates on economic growth. Some argue that the high tax rates discourage work effort, investment, and entrepreneurship among high-income earners, hindering economic growth. Others contend that the high tax rates reduce income inequality, fund government programs and infrastructure, and create a more stable economic environment.

I will delve into the economic history of the post-WWII context later in the blog, but it will be necessarily to cover some of that history presently.

Because of the alleged drag high rates of taxation are theorized to have on the economy, with the fall in the rate of profit indicating that the post-war boom was not sustainable (without much consideration by progressive economists of the problem of rising OCC), President John F. Kennedy proposed a shift in tax policy. The Revenue Act of 1964 was passed under Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, and reduced the top marginal tax rate from 91 percent to 70 percent as part of efforts to stimulate economic growth amid a fall in the rate of profit. Kennedy and his advisers, in conjunction with the Chambers of Commerce, believed that lower tax rates would provide businesses with more incentives for investment, leading to increased economic activity. The government joined Kennedy’s tax cuts with changes in immigration policy, effectively opening America’s borders to immigrants from across the planet, and rolling out a globalist agenda that incentivized the offshoring of manufacturing.

Proponents of the Kennedy tax cut, as with the Reagan tax cuts, argue that the tax rate reduction during Kennedy’s presidency, combined with other factors such as increased government spending, contributed to the economic expansion of the 1960s. On the other hand, critics argue that the cuts primarily benefitted the wealthy and did not necessarily cause the increased economic growth. They suggest that the economic expansion during the 1960s was influenced by other factors, such as demographic change, fiscal policies, and technological advancements. They point out that high-income individuals often have a lower propensity to spend and may opt to save or invest their additional income rather than stimulate economic activity. In other words, the economic impact of tax policies is multifaceted and depends on various factors, including the specific economic context, other policy measures in place, and the overall fiscal environment. Tax rates are just one component of a complex system, and their effects can be influenced by a range of factors.

Can economic growth lead to increased tax revenues without raising tax rates. Indeed, it can happen with and because of tax cuts. How much it affects economic growth and revenues is the better compound question. But here’s the theory. When the economy expands, businesses generate more profits, individuals earn higher incomes, and consumption levels rise. This can result in higher tax collections from income taxes, corporate taxes, and sales taxes. It moreover allows businesses to realize surplus value in profits which allows for investment in new plant and equipment and expansion of value-producing sectors.

This approach is sometimes known as supply-side economics, which gets a bad wrap among progressives who advocate a more Keynesian approach, an approach focused on the demand side, and, more recently, modern monetary theory (MMT), two theories I discuss later on. But to stay with supply-side theory for the moment, this brand of economics emphasizes the importance of factors influencing the supply of goods and services in driving economic growth and prosperity. Proponents argue that policies aimed at reducing tax rates, removing regulatory barriers, and promoting incentives for production and investment stimulate economic activity and improve overall economic performance, which in turn raises revenues.

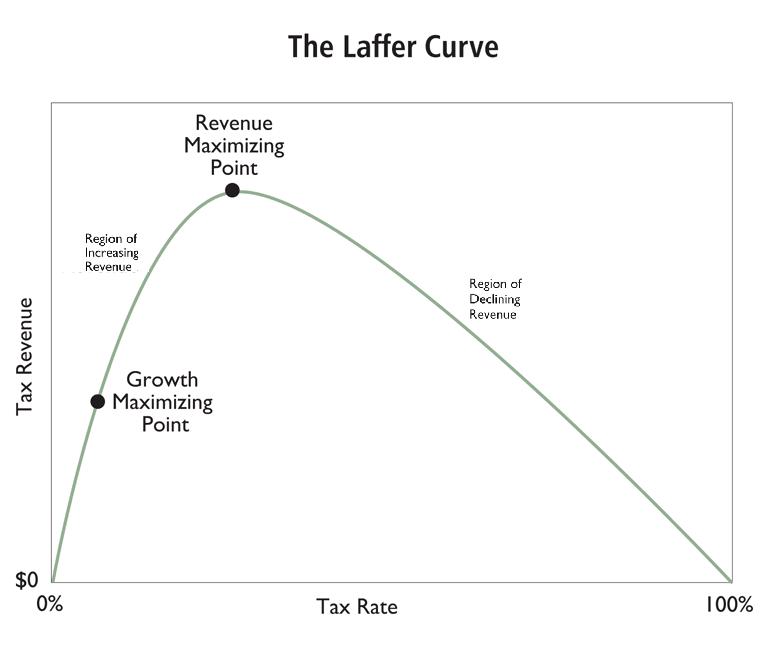

The logic of the argument is illustrated by the infamous Laffer curve (see above), named after economist Arthur Laffer, theorized that that there is an optimal tax rate that maximizes government revenue beyond which further increases in tax rates can lead to diminishing tax revenue. The Laffer curve posits that at very low tax rates, such as zero percent, the government would generate no revenue because there would be no tax base. As tax rates increase, the incentive to engage in productive economic activities, to invest and work, decreases, leading to a decline in taxable income and, consequently, a reduction in tax revenue. On the other side of the curve, at very high tax rates, the Laffer curve suggests that excessive tax burdens can discourage economic activity and lead to tax avoidance or evasion. This can result in a decrease in taxable income and, ultimately, lower tax revenue for the government. Somewhere between these extremes is a theoretical sweet spot. The evidence supporting the effectiveness of supply-side economics and the validity of the Laffer curve is subject to debate. While some empirical trend studies and historical examples have shown positive outcomes from supply-side policies, others have suggested more nuanced or limited effects. But the theory has not been refuted and it remains intuitive.

Supply-side economics, as well as neo-classical approaches and the Austrian School, challenged Keynesian economics, which was hegemonic for decades following WWII. Keynesian economics, or Keynesianism, is named after the British economist John Maynard Keynes, one of the most influential economists of the 20th century. Keynes challenged classical economic theory, which held that markets would naturally reach a state of equilibrium and that government intervention in the economy should be minimal. Keynes argued that the economy could experience prolonged periods of high unemployment and underutilization of resources, and that market forces alone would not necessarily correct these imbalances. He believed that during times of economic downturns, the government should step in to stimulate aggregate demand through increased spending and monetary policy measures.

One of Keynes’ key ideas was the “multiplier effect.” According to this concept, an initial increase in government spending or investment can lead to a larger overall increase in national income. If the government spends money on infrastructure projects, Keynes theorized, it creates jobs and income for workers, who then spend their earnings on goods and services, thereby stimulating further economic activity. Keynes also advocated for using monetary policy to manage the economy, arguing that central banks should adjust interest rates to influence investment and consumption. During periods of economic recession, Keynes suggested that central banks lower interest rates to encourage borrowing and spending, thereby stimulating economic activity. In his theory, then, the government acts as a counterweight to the vagaries of the capitalist market, pulling the economy up when it’s down and keeping it from overheating when it’s up.

Keynesian economics gained significant prominence during the Great Depression of the 1930s when many economies worldwide were grappling with high unemployment and stagnant growth. Keynes’ ideas provided a theoretical framework for governments to implement policies such as fiscal stimulus and monetary easing to combat recessions. While Keynesian economics has faced criticism, it has had a lasting impact on economic thought and policymaking. Keynesian principles influenced the development of welfare states, the use of fiscal policy to manage aggregate demand, and the understanding that government intervention can play a crucial role in stabilizing the economy. Many governments still employ Keynesian-inspired policies during economic downturns, with a focus on increasing government spending, cutting taxes, and implementing expansionary monetary measures to stimulate economic growth and reduce unemployment.

In contrast to Marxist solutions to economic instability and inequality, such as the abolition of property in land and of all rights of inheritance, confiscation of the property of all emigrants, nationalization of industries and other instruments of production, Keynesian ideas were taken up by progressives, who saw a chance to integrate further the administrative state and technocratic apparatus with the social logic of corporate governance and bureaucratic rationalization. Thus Keynesianism was a justification for more thoroughgoing corporatist arrangements and greater manipulation of the thoughts and actions of the masses for the sake of avarice.

(Sorry. One more note. Not all policies sketched in the Communist Manifesto have been eschewed by capitalist elites. A heavy progressive or graduated income tax was a plank in the 1848 platform. As the foregoing makes obvious, progressive income taxes have been incorporated in modern state capitalist systems, including the United States. However, this is not a communist plot. What capitalist elites have cribbed from the communists is borrowed in order to the undermine the organized proletarian movement by ameliorating systemic discontents inherent in the capitalist mode of production. The effect of this has been to disorganize the proletarian movement. This strategy is what elites call “social democracy,” or, as it known in the United States, “progressivism.”)

Against the Keynesian demand management approach, a resurgent Austrian School, led by Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, gained prominence in the mid-twentieth century. The Austrian School advocated for a more laissez-faire approach, emphasizing the role of individual decision-making, market processes, and the limitations of government intervention. Hayek and von Mises were critical of Keynesian policies, particularly the use of fiscal stimulus and the belief in the government’s ability to effectively manage the economy. They argued that excessive government intervention and monetary expansion distorts resource and capital allocation and ultimately produces economic instability. During the 1970s, when Keynesian economics faced challenges in addressing stagflation (a combination of high inflation and high unemployment), the Austrian School gained attention for its critique of Keynesian policy prescriptions. Austrian economists argued that the business cycle fluctuations and structural imbalances resulted more from government intervention, particularly through monetary and fiscal policy rather than from external shocks and government aloofness.

Perhaps more profoundly, and here we come to the expression of libertarianism that continues to move American politics on the right, the Austrian School provided people with a philosophy of personal autonomy and individual freedom, which many young people found very attractive. Both von Mises and Hayek expressed concerns about the dangers of authoritarianism and totalitarianism, emphasizing the importance of economic freedom, individual autonomy, private property rights, and the rule of law as essential components for human flourishing that underpinned societal well-being (if such a thing could be said to exist). Their works emphasized the need to protect individual liberties, defend the principles of free markets, and maintain a system that respects the diverse knowledge and preferences of individuals.

Von Mises wrote about this in his 1949 Human Action. Because individuals possess unique knowledge and subjective preferences, he reasoned, centralized planning and intervention by authorities is unable to efficiently allocate resources. Like Adam Smith and his metaphor of the “invisible hand,” Von Mises believed that market processes, guided by voluntary exchanges and the profit motive, enable individuals to coordinate their actions and allocate resources effectively. The alternative, the expansion of government control, would lead to detrimental consequences for both economic prosperity and individual liberty. Central planning and government intervention lead to distortions and inefficiencies, as well as the suppression of personal freedoms. Totalitarian regimes represented grave threats to human flourishing and warned of the erosion of individual rights under such systems.

Friedrich Hayek, in his 1944 book The Road to Serfdom, examined the dangers of central planning, collectivism, and the erosion of individual freedom. He argued that the concentration of power in the hands of a central authority inevitably leads to the problems of authoritarianism and totalitarianism. Hayek cautioned against the idea that a planned economy could achieve desirable outcomes, highlighting the importance of individual choice and spontaneous market processes in the determination the price system. Hayek believed that the values of individual liberty, limited government, and private property rights, were essential for maintaining a just and prosperous social order. In his 1960 book The Constitution of Liberty, Hayek defends the idea that spontaneous order, emerging from the interactions of individuals pursuing their own goals within a framework of rules, leads to better outcomes than centrally planned or directed systems. He warns against the dangers of collectivism, central planning, and the concentration of power, arguing that these approaches undermine personal freedom, individual responsibility, and economic prosperity.

In my course, Freedom and Social Control, which begins with the big ideas of liberty and democracy, I assign my students excerpts from Marx and Engels’ The Communist Manifesto (the preface to the Skyhorse editions penned by yours truly) and Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom and The Constitution of Liberty. I explain that Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom implemented policies in the 1980s that reflected elements of both the Austrian School and supply-side economics. These leaders pursued deregulation, tax cuts, and market-oriented reforms with the aim of reducing the role of government in the economy and stimulating economic growth. I explain to them that this is the context in which I came of age and that these developments framed the macroeconomic situation their parents faced when they came of age generation later. Of course, progressive economic ideas also contributed to this framework. Indeed, these are the competing macroeconomic theories that underpin the current political debates over the character and scope of democracy, equality, and freedom.

I then play them this video by Marxist anthropologist and geographer David Harvey (or rather the RSAnimate version of it because it is more entertaining and increases engagement) to raise the problem of capitalist crisis and ways of understanding that problem.

Earlier I mentioned Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). So what about that? MMT is an economic framework that challenges traditional views on fiscal and monetary policy. MMT emphasizes that governments with sovereign control over their own currency can issue it without default risk if the currency is not pegged to another currency or tied to a fixed exchange rate. MMT suggests that the primary role of fiscal policy should be to achieve full employment and price stability, rather than focusing on balancing budgets. It argues that governments should use their fiscal capacity to stimulate or cool down the economy as necessary, with taxes acting as a tool for demand management. MMT proposes a job guarantee program where the government acts as an employer of last resort, offering a job to anyone willing and able to work. This is seen as a way to maintain full employment and stabilize the economy.

One obvious criticism is that MMT downplays the risks of inflation, and in the current situation that is a concern. Critics argue that excessive government spending without corresponding increases in productivity or supply capacity can lead to inflationary pressures, eroding the purchasing power of money and potentially destabilizing the economy. Here again, the history of Argentina and the current reality of Venezuela are thrown in the faces of MMT advocates. MMT’s focus on government spending capacity and the ability to create money raises concerns about the potential impact on interest rates. Critics argue that increased government spending financed by money creation could lead to higher interest rates, as the supply of money increases faster than the demand for borrowing.

MMT’s emphasis on currency sovereignty and fiscal capacity downplays the real resource constraints on an economy. Critics argue that an economy’s productive capacity, including capital, labor, and natural resources, imposes limits on sustainable government spending and that excessive government intervention can misallocate resources and hinder long-term growth. Critics also highlight the potential political challenges associated with implementing MMT policies. The ability to use fiscal policy more liberally may lead to debates about the appropriate level of government intervention, potential inefficiencies, and the risk of favoritism or rent-seeking behaviors. And what about globalization? That’s what made Keynesianism a dinosaur. (We are coming to that.)

Earlier I noted the selling of bonds to fund the government. (I almost had an argument on Facebook about bonds in the scope of MMT recently, but decided that the level of competency of my audience precluded any productive discussion of the matter. However, it did inspire my decision to include a treatment of MMT in this blog.) Bonds are debt instruments issued by governments, corporations, and other entities to raise capital. They are typically bought by a wide range of investors, including individuals, institutional investors, and foreign entities. Individual investors include retail investors and households that purchase bonds directly or indirectly through mutual funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), or retirement accounts, a pool of investment resources used by transnational corporates (TNCs) to entrench globalization. There are also institutional investors, such as pension funds and insurance companies, that often invest in bonds as part of their portfolio diversification and income generation strategies. These large-scale investors can buy bonds in significant quantities. But so can individuals who have the wealth to invest in low-yield long-term assets.

Banks and financial institutions, including asset management firms, and commercial and investment banks, hold bonds as part of their investment portfolios. They may also act as intermediaries, facilitating bond transactions for their clients. Central banks, such as the Federal Reserve in the United States (or the European Central Bank), hold government bonds as part of their monetary policy operations. They purchase bonds in the open market to influence interest rates or provide liquidity to the banking system. Foreign governments, sovereign wealth funds, and international financial institutions also hold bonds. This includes foreign entities investing in the bonds of both developed and developing (and underdeveloped) market economies. Bond mutual funds and ETFs pool together funds from multiple investors and invest in a diversified portfolio of bonds. Investors can purchase shares of these funds, indirectly gaining exposure to a broad range of bonds.

While the traditional perspective sees bonds as a means for governments to borrow money from the public to finance expenditures, MMT offers a different perspective (this is what my Facebook interlocutors didn’t understand). According to MMT, a sovereign government that has control over its currency and issues debt in its own currency can create money through fiscal policy. It argues that such a government can spend money into the economy without being solely reliant on borrowing or tax revenue. In this context, bonds are seen as unnecessary for government financing and are not required to fund government spending. Proponents of MMT argue that the primary purpose of issuing bonds is to manage interest rates and provide a safe financial instrument for investors. To be sure, the government can use bonds to drain excess reserves from the banking system and control inflation by influencing interest rates. However, according to MMT, these interest rate management operations can be achieved through other policy tools, such as adjustments to the reserve requirements or interest paid on reserves.

The point is that, in the MMT framework, government spending is not constrained by the need to issue bonds or by concerns about accumulating public debt. Instead, the focus is on the impact of fiscal policy on the real economy, such as inflation, productive capacity, and unemployment. Critics of MMT express concerns about the potential inflationary risks associated with increased government spending without the discipline imposed by bond issuance. They argue that the absence of bonds could lead to excessive money creation and inflationary pressures. In other words, the question of bonds is one of the main bones of contention.

MMT can be seen as compatible with Keynesian economics, as both frameworks share some common objectives and principles. This is one of the reasons progressives have glommed onto MMT as Keynesianism have flailed about. Recall that Keynesian economics emphasizes the role of aggregate demand in determining economic outcomes and advocates for active government intervention through fiscal policy to stabilize the economy. According to this view, during recessions or periods of low demand, government spending should increase to stimulate economic activity and reduce unemployment. MMT focuses on the monetary operations of governments and challenges conventional notions of government budget constraints and debt. It argues that sovereign governments with control over their own currency can spend money into the economy to achieve full employment and control inflation, without being limited by revenue or the need to borrow.

Keynesian economics can be seen as providing the policy prescriptions and fiscal framework that align with MMT’s theorization of the fiscal space available to governments. MMT provides additional insights into the monetary operations and constraints faced by governments, which can further inform Keynesian policy recommendations. Both frameworks advocate for government intervention to stabilize the economy, promote full employment, and manage inflationary pressures. They share a common goal of utilizing fiscal policy to achieve macroeconomic objectives.

However, as I noted earlier, Keynesian strategies are not as effective as they used to be—and this has implication for MMT. Globalization has significantly increased the interconnectedness and interdependence of economies, and Keynesianism depended on the capitalist world economy, the nation-state, the international system, and the historical-conjunctural event of WWII and its aftermath. Analysts of the present situation must consider the global context and interconnectedness when formulating and implementing economic policies considering the constraints international economic integration imposes national economies.

In a globalized economy, capital flows freely across borders. Increased capital mobility can limit the effectiveness of Keynesian policies, as expansionary fiscal or monetary measures in one country can lead to capital outflows, currency depreciation, and potential economic imbalances. Highly-mobile capital allows investors to globetrot, moving their capital to different countries in search of higher returns or safer investment environments. This constrains the ability of governments to independently stimulate the economy through fiscal policy. When a government implements expansionary fiscal policies, such as increased government spending or tax cuts, it sows concerns among investors about fiscal sustainability, inflation, or currency depreciation. In response, capital flows out of the country, putting downward pressure on the currency, raising borrowing costs, and potentially undermining the intended effects of fiscal stimulus. Globalization makes the movement routinely and systemically viable. Monetary policy, particularly through central bank actions, has thus gained prominence in economic management. Central banks use interest rate adjustments and unconventional measures like quantitative easing to influence economic conditions. With monetary policy taking a more prominent role, fiscal policy has relatively less influence and scope for direct intervention.

Globalization has led to increased trade and competition. Countries are now more interconnected through supply chains, and businesses operate in a globalized marketplace. This means that the impact of domestic fiscal stimulus measures on overall economic activity can be influenced by factors such as import levels, exchange rates, and global demand conditions. Changes in domestic demand alone may not have the same multiplier effects on employment and output if a significant portion of the demand is met through imports or if domestic producers face intense international competition. Many countries have faced increasing levels of debt, which can limit the ability of governments to engage in expansionary fiscal policies. High levels of debt raise concerns about fiscal sustainability, potential crowding out effects, and the risk of rising interest rates. These constraints can limit the scope and effectiveness of Keynesian policies that rely on increased government spending.

Moreover, in a globalized world, the economic policies implemented by one country can have spillover effects on other countries. Expansionary fiscal policies in one country can lead to trade imbalances, currency fluctuations, or inflationary pressures that spill over to other economies. These spillover effects can complicate policy coordination and limit the ability of individual countries to independently implement Keynesian policies without considering the potential repercussions on other nations. Globalization and international agreements, such as trade agreements or fiscal stability commitments, introduce external constraints on domestic fiscal policy. Countries may have to adhere to fiscal rules or commitments that limit their ability to engage in substantial deficit spending or provide state aid to industries. Such constraints restrict the flexibility of governments to use Keynesian mechanisms to stimulate domestic demand during economic downturns. This is the problem of transnationalization and the loss of national sovereignty amid the deepening globalization of the capitalist mode of production.

Finally, in a globalized world, currencies are subject to fluctuations in response to various economic factors. If a country implements MMT policies that result in a significant increase in government spending or a larger fiscal deficit, it may put downward pressure on the country’s currency. This can lead to currency depreciation, affecting trade competitiveness and potentially impacting the effectiveness of MMT policies. Globalization has facilitated greater mobility of capital across borders. If a country implements MMT policies that result in increased government debt or deficit spending, it may lead to concerns among international investors about the country’s fiscal sustainability. These concerns can trigger capital outflows, increasing borrowing costs, and potentially limiting the government’s ability to finance its spending through debt issuance. This could constrain the implementation of MMT policies.

The success of Keynesian economics is thus temporally bounded. It worked because of a unique world situation, a historical-conjunctural moment, if you will. The post-World War II era presented a unique economic environment with significant slack in the world economy and reconstruction needs in several regions. This contributed to the actual and perceived effectiveness of Keynesian economics during that time. The aftermath of World War II required substantial reconstruction efforts, particularly in war-torn countries. This created a surge in demand for goods and services, providing an opportunity for Keynesian policies to stimulate economic activity and employment. Government spending on housing, industrial revitalization, and infrastructure projects helped absorb the excess capacity and unemployed resources, contributing to economic growth.

During the war, the US government had increased military spending to support the war effort. This spending had a stimulating effect on the economy, boosting industrial production, creating jobs, and reducing unemployment, thus tapping the industrial reserve that had expanded during the Great Depression. However, after the war, with the cessation of hostilities, the need for such high levels of military expenditure diminished. In keeping with past practices, the war’s end brought a drastic demobilization of military personnel and a transition from wartime production to peacetime activities.

This period of economic contraction, known as the “postwar recession” or, more positively, the “wartime-to-peacetime transition,” resulted in the return of high levels of unemployment and excess labor supply. Industrial restructuring involved retooling factories and retraining workers, which also caused disruptions in the labor market. The significant number of soldiers returning to civilian life (approximately 16 million Americans served in the armed forces during World War II) put pressure on the labor market. The sudden influx of veterans seeking jobs increased competition, leading to an increase in unemployment rates and plunging wage floors across sectors. Progressives realized they had to do something drastic to keep the masses from defecting wholesale to the Republican Party, so they turned to Keynesian policies, such as increased government spending or public works programs, which helped generate employment opportunities, reduce unemployment, and boost aggregate demand.

The argument made sense and Keynesianism came into its own. The war effort had utilized significant portions of productive capacity for military production. After the war, there was an abundance of underutilized industrial capacity that could be used for civilian production. Keynesian policies aimed at stimulating consumer demand, such as tax cuts or government transfers, and this helped activate the idle capacity and promote economic growth.

Governments had more flexibility in implementing expansionary fiscal policies during the post-war period due to lower public debt levels (in contrast to today) and a general willingness to use deficit spending for economic reconstruction. Fiscal stimulus through government spending or tax cuts could be deployed without concerns about high debt burdens or borrowing costs, allowing for a more robust application of Keynesian principles. The post-war period was characterized by a broad acceptance of Keynesian economics and the role of government intervention in managing the economy. Governments had a strong political mandate to address the challenges of reconstruction, and there was a belief that active government involvement could bring about economic stability and growth.

In addition to investment in public infrastructure, one of the primary wages the US government stimulated and stabilized economic growth during this period was by remobilizing its military forces and entering a cold war with the Soviet Union by initiating the policy of containment. The renaming of the Department of War to the Department of Defense, the result of the National Security Act of 1947, which restructured the military and national security apparatus of the United States to reflect the broader strategic focus on maintaining military preparedness ostensibly in the face of the growing geopolitical tensions, signaled the establishment of what President Dwight D. Eisenhower, in his farewell address to the nation on January 17, 1961, called the military-industrial complex, which he described as the “conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry.

During the Cold War era, which lasted from the late 1940s to the early 1990s, the United States significantly increased its military spending. Military spending as a percentage of US gross domestic product (GDP) saw a substantial increase. In the late 1940s, military spending accounted for approximately five percent of GDP. By the late 1950s, during the height of the Cold War, it had reached a peak of around ten percent of GDP. Throughout much of the Cold War period, military spending consistently remained above five percent of GDP. The US government invested heavily in defense programs, such as the development of nuclear weapons, missile defense systems, and various military technologies. The United States maintained a large military force during the Cold War. In 1950, the active-duty military personnel numbered around 1.5 million. By 1968, at the height of the Vietnam War, it reached its peak at approximately 3.5 million. The number of active-duty personnel gradually decreased in the following years, but the United States maintained a significant military presence throughout the Cold War. Today, there are roughly 1.3 million active-duty military personnel and another million or so reserve and National Guard members.

The increase in military spending during the Cold War had various economic implications. On one hand, it stimulated sectors of the economy, such as defense industries and technological advancements. This is still true today. On the other hand, it required substantial government resources that could have been allocated to other areas like social programs or infrastructure projects. This is true for other nations, as well. For example, NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization), a intergovernmental military alliance formed in 1949 to promote collective defense and cooperation among its member countries, expects countries to contribute to their own defense capabilities and asks them to meet certain defense spending targets. NATO member countries have committed to allocate a certain percentage of their GDP towards defense spending. In 2006, NATO established a guideline for member states to strive towards allocating at least two percent of their GDP to defense expenditures.

The increased government spending on defense had a multiplier effect on the economy. It created jobs, generated income, and stimulated demand for goods and services. The defense industry, along with its supply chains, played a crucial role in fueling economic growth, especially in the manufacturing sector. The production of military equipment, technological advancements, and research and development efforts were significant contributors to economic expansion during this period. Furthermore, the Cold War spending also had indirect effects on the economy. It stimulated technological innovation, especially in areas such as aerospace, electronics, and communications. These innovations not only benefited the defense sector but also had broader applications in the civilian economy, spurring further economic growth and productivity gains.

The point I intend by going through this history is that one reason why there is so much recalcitrance among those who are in a position to reduce defense spending is that they recognize that this budget item—the largest item in the discretionary spending portfolio—is one of only remaining instruments in its possession that allows the state to complete the faltering circuit of capitalism (faltering because of the inherent contradiction in the capitalist mode of production explained earlier in the blog). Defense spending allows for investment in high technology while reducing the scope of the industrial reserve by employing millions of otherwise redundant workers, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Moreover, weapons sales generate tens of billions of dollars for defense contractors and related industries. For example, sales of US military equipment to foreign governments rose 49 percent to $205.6 billion in the latest fiscal year, according to the US State Department in a recent report. Companies that benefit from these sales include General Dynamics Corp, which makes the Abrams tank, Boeing, which makes the F-15 jet, and Lockheed Martin Corp, which makes ships.

Reflecting on everything I have written here, there are two observations I want to make in concluding. First, this is a lengthy blog and lots of things compete for my time and I recognize that it could be better organized and content more succinctly put. If it helps, think of it as a set of notes. (That’s how I am looking at it.) Second, on the question of what is to be done, if revenues cannot be generated to finance national priorities, then tough decisions have to be made concerning what those priorities are going forward. We cannot keep leaving successive generations with ever more debt. The debt they’re being burdened with is not a useful inheritance, as much of it, despite completing the circuit of capitalist accumulation, does not advance the means of production in a way that creates opportunity for the masses to generate wealth for themselves. Neoliberalism and other rationalizations are just so much rent seeking that advances the longterm interests of no one but the superrich. And this explains why they are moving the world towards a system of global neo-feudalism ruled by a transnational corporate state apparatus. They know the capitalist mode of production is coming to an end. They are desperately trying to protect their opulence.